|

BANDELIER

Guidebook 1941 |

|

Bandelier National Monument

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT is located on the Pajarito Plateau in the canyon and mesa country of northern New Mexico, 20 miles west of Santa Fe, the State capital. Lying between the Rio Grande, New Mexico's largest river, and the Jemez Mountains, it is about 45 miles from Santa Fe by highway.

The monument was established in 1916, primarily to preserve and protect the important prehistoric ruins of the region. The area is characterized by jagged cliffs of pinkish rock, forested mesas, and rolling hills.

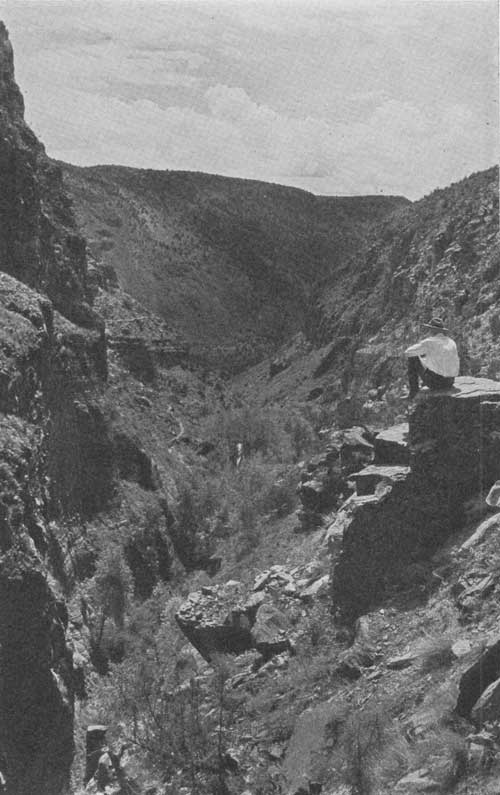

The Pajarito Plateau is of interest geologically as well as archeologically. It is constituted largely of tuff, or consolidated volcanic ash, and basaltic lava ejected thousands of years ago from the great volcanic crater—perhaps the largest in the world—whose rim today forms the Jemez Mountains. Through this large plateau of volcanic material, running water has cut many steep-walled canyons down to the Rio Grande. One of these, the Frijoles, is the area of major interest in the monument, for here are situated both the best-known archeological ruins and the monument headquarters development. South of Frijoles Canyon is an undeveloped area of some 25,000 acres of wilderness, traversed only by trails.

Bandelier, like much of northern New Mexico, has a delightful summer climate. Lying in forested mountain country at an altitude of about 6,500 feet at the headquarters, it has a range in elevation of more than 1,500 feet. Summer nights are cool, and fall and spring are delightful. During the winter there is considerable snowfall; for winter sports enthusiasts, good skiing is available in the Jemez Mountains to the west of the monument.

Bandelier National Monument is named for the great historian, ethnologist, and traveler, Adolph F. A. Bandelier, whose several years' visit to New Mexico in the 1880's included a stay in the canyon of the Rito de los Frijoles. Engaged in 1880 by the Archeological Institute of America, he conducted research in the Southwest for nearly a decade, living among the Pueblo Indians in order to study their life at first hand.

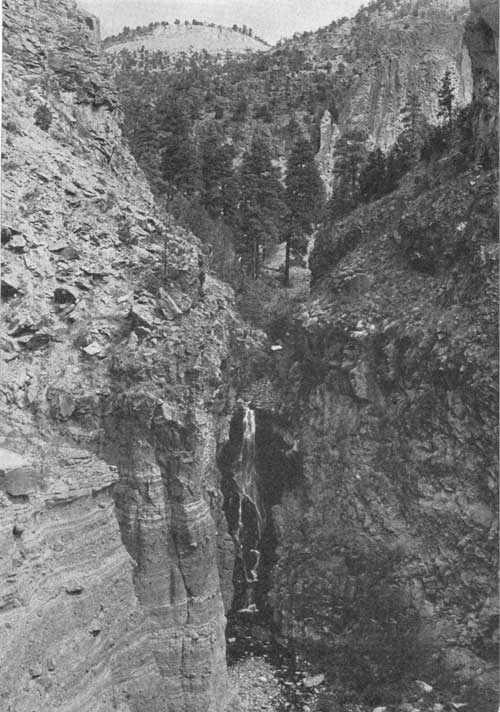

The upper fall of the Rito de los Frijoles drops about 80 feet |

FRIJOLES CANYON

UP THE canyon from the end of the road near the headquarters of the monument, lie the most important ruins and cliff dwellings of the area. Most of these sites are within a few minutes' easy walk from the lodge and museum.

The Rito de los Frijoles is a particularly interesting and scenic setting for these sites, which were occupied from approximately the thirteenth to the sixteenth centuries.

TYUONYI, THE COMMUNITY HOUSE

THE MAJOR ruin of Frijoles Canyon is a large circular pueblo site on the valley floor, sometimes known as Tyuonyi, which was the Cochiti name for the canyon, meaning "meeting-place."

Most of the excavation of this ruin was accomplished in 1908 and 1909 by the School of American Archeology; it was repaired and stabilized by the National Park Service in 1937.

Tyuonyi is approximately circular, comprising the remains of between 200 and 300 small rooms of rather crude masonry around a large circular plaza. The walls were probably completely covered with adobe plaster. It is believed the building was originally two-storied, and that certain sections were even three stories high.

More than 200 rooms on the ground floor have been excavated, and there are still a number of unexcavated rooms on the northeast side. The rounded plaza is nearly 150 feet across; it is surrounded by four to seven tiers or concentric rings of the contiguous rectangular rooms.

There are three kivas, or circular subterranean ceremonial chambers, sunk into the northeast side of the plaza, close to the dwelling rooms. One of these was excavated in 1908 and repaired in 1938.

On the southwest side is the only entrance to the ancient village; a narrow, easily defended passageway leading directly into the plaza, with no side entrances. Although it appears at first glance like a planned structure, the pueblo apparently grew gradually, the northeast side perhaps being the first to be built and the southwest the last.

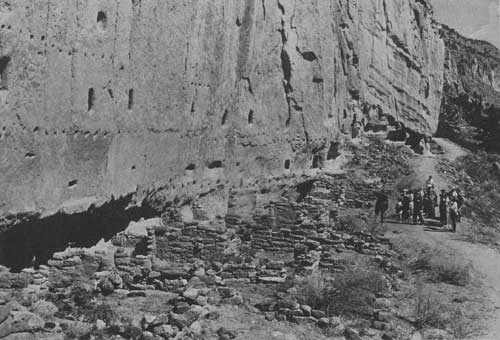

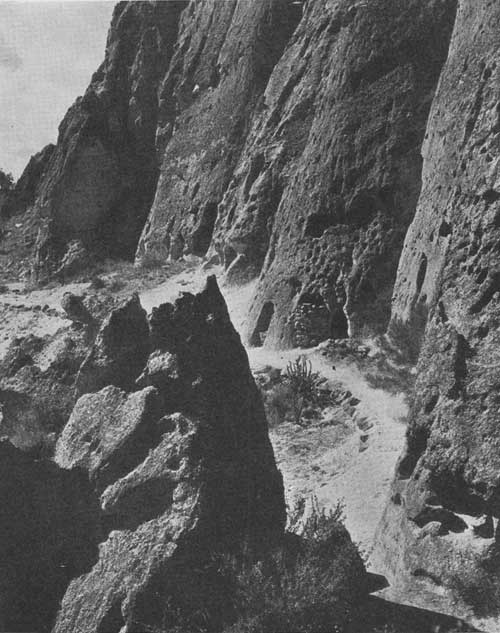

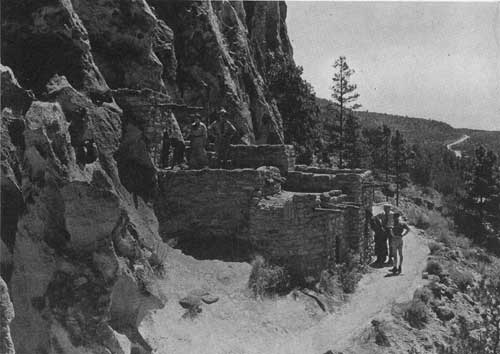

Visitors stop to study the ruins along the wall of the canyon. The holes in the cliff once supported floor beams in this community dwelling |

THE BIG KIVA

DOWN THE canyon from the community house, there are a small unexcavated ruin and a great kiva on the valley floor. The large kiva was excavated in 1908, and reexcavated and repaired in 1937. About 42 feet in diameter, circular, it was dug deep in the earth and lined with a stone wall which probably rose just above the ground level. Six large logs were set vertically in two rows on the floor. Other logs, laid across from side to side of the wall and supported by these six uprights, formed the framework of the roof. Entrance into the kiva is believed to have been through the roof, by a hatchway and a ladder, as in modern kivas.

Swimming pool on the Rito de los Frijoles, a short distance down the canyon from the campground |

THE TALUS VILLAGES

ON THE north side of the canyon are steep cliffs of tuff, with slopes of talus, or accumulated rock and dirt, at their base. Since this tuff is comparatively soft, it was possible to cut it with stone axes; the prehistoric Pueblo Indians had no metal, but used stone and bone for tools.

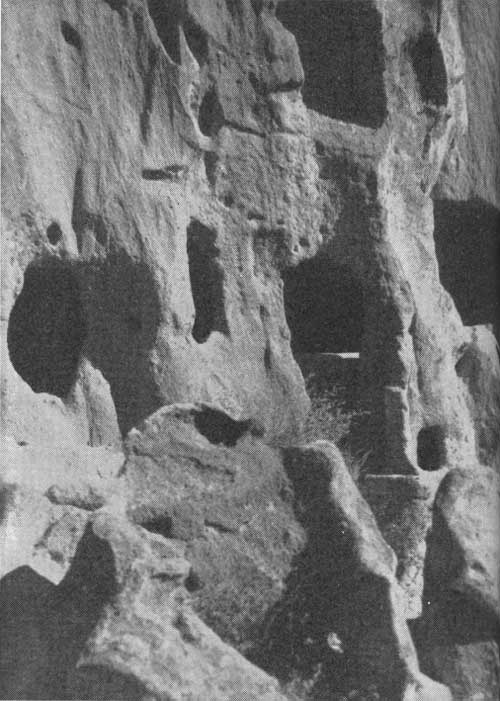

Thus small houses were built against the cliffs at the top of the talus slopes, and natural caves were used in conjunction with them. Holes were chopped into the soft rock for the roof beams, and even small rooms were carved.

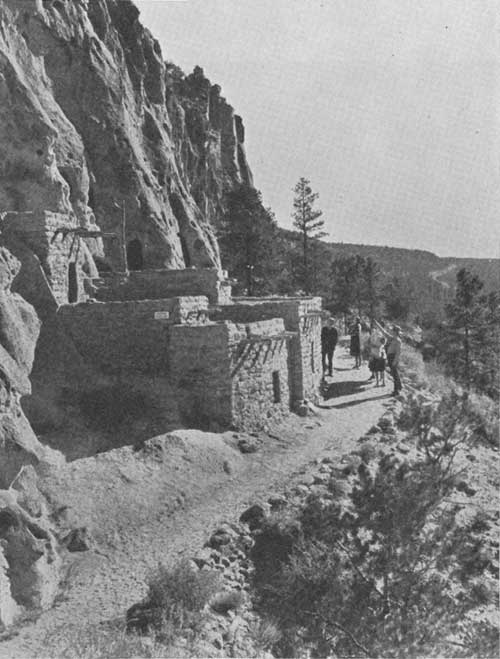

In the Rito de los Frijoles Canyon these talus villages, or cliff houses and cave rooms, extend for 2 miles along the north cliff. One unit has been restored, and several cave rooms with smoothed floors and smoke-blackened ceilings may be visited. Farther up the canyon may be seen the holes in which were inserted the ends of the roof beams of second and third stories. Beneath these holes are the remnants of rock walls of rooms built on the talus in front of the cliff.

While the talus villages were built at about the same period as the ruins on the valley floor, it is quite possible that the cliff houses were occupied somewhat earlier, and that the large community house represents a fusion of the scattered families into one large, defensible village. If all the cliff dwellings were occupied at the same time, there must have been several hundred people living in them—possibly more than a thousand—in addition to the inhabitants of the pueblos on the valley floor.

THE "CEREMONIAL" CAVE

SOME distance up the canyon from the talus villages and Tyuonyi is a cavern situated in the north cliff about 160 feet above the canyon floor. In this cave, reached by ladders and a rock-cut trail, the remains of a kiva and about 20 ordinary rooms have been found.

Restored in 1909 and repaired again in 1938, the kiva was found to be well-preserved, although only the outlines and the foundations of the other rooms remain. On the first story there seem to have been 13 rooms, with three small cave rooms possible for storage. Outlines of walls on the smoke-blackened ceiling indicate several second-story rooms as well.

The kiva, excavated into the rock floor, was entered into through a hatchway in the roof. There is no real reason for calling this cave "ceremonial;" it was an ordinary habitation, so far as can be seen, differing from others only in its difficulty of access and consequent defensibility. Evidently one small group of families lived in this cave, preferring to carry their food and water up the cliff than to live in the open, exposed to enemy attacks.

View into Frijoles Canyon from above the upper falls, showing White Rock Canyon along the Rio Grande in the distance |

THE SOUTHERN PORTION

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT includes a large area of undeveloped, roadless wilderness—some 25,000 acres of parallel canyons and narrow mesas traversed only by foot and horse trails—between the Rio Grande and the Jemez Mountains, south of Frijoles Canyon.

This section and its features are much like the Frijoles area and that traversed in driving to Frijoles. While this portion of the monument is not frequently visited, there are a number of smaller prehistoric sites in the area, two of which are especially unusual.

THE STONE LIONS

ON A narrow mesa known as the Potrero de las Vacas, an outcrop of tuff is rudely carved into the semblance of a pair of mountain lions about 6 feet long and 2 feet high, crouching side by side with tails extended.

Nearby on the same mesa point there is a large pueblo ruin known as Yapashi or Hapashenye, which was occupied approximately at the same time as the Frijoles Canyon sites. The stone lions were probably carved by the people of this pueblo, ancestors of the modern Cochiti and/or other Keres pueblo Indians.

The mountain lion is an important animal in Cochiti ritual and belief. Thus the stone lions are a sacred shrine to which, for many years, Indians from Zuni—200 miles distant—have made pilgrimages. Such full-size sculptures as these are very rare north of southern Mexico.

A close-up of the cliff dwellings in which lived prehistoric Indians |

THE PAINTED CAVE

THE OTHER unusual feature of interest in the southern portion of Bandelier is a great cave, "La Cueva Pintada," a few miles south of the stone lions. Centuries ago, it is believed, the people of a small talus village nearby embellished this cave with pictographs. Painted in red, white, and black, they include both geometric designs and life forms, notably the mythical "feathered serpent."

THE OTOWI SECTION

A SEPARATE portion of Bandelier National Monument is traversed by the motorist en route to Frijoles Canyon from Santa Fe. This detached area was set aside to protect two large pueblo ruins, lying in typical Pajarito Plateau country.

POTSUI'I (OTOWI)

ONE of the two ruins in this section is on a low ridge in the heart of a canyon, walled in by high cliffs of tuff. This pueblo site—Potsui'i, or Otowi—is a large ruin, but contains few features of special interest. It was largely excavated by collectors years ago. Some repair work has been undertaken there by the National Park Service.

Tyuonyi, the large surface ruin on the floor of Frijoles Canyon |

SANKAWI

SANKAWI, sometimes spelled Tsankawi, is the other large ruin in the Otowi section. Atop a small mesa, it affords a magnificent view across the Rio Grande to the east, a mountain panorama of more than a hundred miles from north to south. This view is particularly beautiful during autumn, when the cottonwoods in the river valley and the aspens on the mountain slopes have turned yellow.

Sankawi, a very interesting pueblo ruin, was occupied comparatively late, probably during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. There are kivas which have been cut into the rock in the main ruin on the mesa top, as well as talus villages and cave rooms at the foot of the low cliff on the south side. Especially interesting is the trail to Sankawi across the bare rock of the mesa for some distance to the west, a narrow trench worn or chopped into the rock, in places to depths of several inches to a foot.

Sankawi is a site of great potential scientific importance. Unless it has been extensively vandalized or excavated in the past, systematic investigation by archeologists will yield much useful information.

The conical coyote dwelling along the trail, once occupied by Adolph Bandelier during his researches in Frijoles Canyon |

The roof of the kiva in the Ceremonial Cave, north wall |

PREHISTORY OF PAJARITO PLATEAU

ARCHEOLOGY is the story learned from ruins such as those in Bandelier National Monument; it is the history of mankind as learned from the actual material remains of the peoples and civilizations of the world. The distinction between archeology and history is one of both method and subject; the historian uses as evidence primarily written documents, and is thus largely confined to the study of peoples who had a system of writing and left decipherable documents or other records. The archeologist, studying all varieties of evidence and remains, is usually concerned with peoples who did not know how to write.

In America simple demarcation between archeology and history is provided by the clear separation between the aboriginal, chiefly pre-literate people, and the invaders, chiefly literate, who conquered the New World between about 1500 and 1850. In the United States, therefore, archeologists study the American Indians and their ancestors, while historians study Americans of foreign descent. At times, of course, the two fields overlap.

In the Southwest archeologists have an especially good field for study since the prehistoric peoples have survived to the present day, largely unchanged in essentials, as the Pueblo Indians. The prehistoric remains of the northern portion of the Southwest may be classified and arranged to form a continuous story and present a fairly clear picture. Centuries after the period of the ancient bison-hunters (represented by the famous Folsom points), simple hunting people were living in this area. They were skilled basket and bag makers, and used a device called a spear-thrower, or atlatl, for greater range with their javelins. While they had no houses or pottery, and few tools, they gradually learned how to cultivate maize.

Some 1,500 years ago, at about the time of the collapse of the western Roman Empire, these Basket Makers, as they are called, learned to make fired pottery and to build more or less permanent dwellings: circular pit-houses excavated into the ground, entered through a roof or by a subterranean passage. They also began to build little rectangular structures of masonry on the surface of the earth for storage.

The Talus House beneath the north wall of the canyon |

By about the tenth century they were living in such rectangular surface rooms of stone, retaining the pit-houses as ceremonial chambers, or kivas. This arrangement has persisted in essentially the same form up to the present time.

In the meantime, agriculture continued to develop, stone axes and the bow and arrow appeared, and other advances and alterations of culture occurred. During this period, between 500 and 900 A. D., a new racial element entered the northern Southwest, but apparently brought no important contributions to the Pueblo civilization.

In the following centuries the major change or advance in Pueblo culture was the development from small scattered villages into great urban centers of hundreds or even thousands of people. Among the most outstanding of these large centers of population were the towns of Chaco Canyon and the cliff dwellings of Mesa Verde and northeastern Arizona.

This trend reached its highest point in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, the period of maximum population. During the thirteenth and the fourteenth centuries, especially at the time of the great drought of 1276-1299, many of these towns and associated smaller villages were abandoned. The entire San Juan area of southwestern Colorado, northwestern New Mexico, and northeastern Arizona—previously the major area of Pueblo occupation—was evacuated. The population gradually began to concentrate in the areas still occupied by modern Pueblo Indians: the Hopi mesas and washes, the Zuni country, and the Rio Grande area.

The most significant shift of population was the movement from Chaco Canyon and Mesa Verde to the Rio Grande Valley which had been only sparsely occupied prior to about 1200. From that time to the period of Spanish colonization in the seventeenth century, there were many more villages in the Rio Grande Valley and its tributaries than there are today. During the seventeenth century, the Pueblo population of the Rio Grande region declined sharply.

Among the areas along the Rio Grande intensively occupied by Pueblo Indians from about 1200 to about 1600, but deserted now, is the Pajarito Plateau. Many villages were built in this area, presumably by people from the Chaco, Mesa Verde, and other abandoned regions. Between approximately 1400 and 1600 these people declined in numbers and gradually moved down to the Rio Grande, concentrating at the surviving villages of San Juan, Santa Clara, San Ildefonso, Cochiti, and other settlements.

While the first three of these pueblos have a dialect called Tewa, Cochiti and four other villages to the south and southwest of it speak an entirely different language, Keresan. The boundary between Tewa and Keresan territory is thought to have been near the Rito de los Frijoles. Tsankawi and Potsui'i and other sites of the northern Pajarito Plateau represent ancestors of the Tewa, while the inhabitants of the ruins south of Frijoles Canyon, and probably those of Frijoles Canyon itself, were ancestors of the Cochiti and perhaps other Keresans. It is possible, however, that the occupants of Frijoles Canyon ruins were originally Keresans, but were replaced about the fourteenth century by Tewas.

The villages of the Pajarito Plateau are not definitely mentioned in the Spanish chronicles, even in those relating to early sixteenth-century explorations, during which time some of the sites were surely occupied. Large numbers of the Pajarito people probably had gone by that time to Cochiti and the Tewa pueblos and many of the villages may have been almost deserted. One statement in the Coronado Expedition narratives probably refers to the Pajarito towns, evidently as villages still occupied to a certain extent, or at least used occasionally.

The details of the story of the Pajarito Plateau and the evidence on which it is based can be found in various technical reports and works of reference, a few of which are listed at the end of this booklet. These details are also shown graphically in the Bandelier National Monument museum, together with exhibits on the modern pueblos and on the geology of the area.

The east section of the coyote ruins in Frijoles Canyon, looking northward from Tyuonyi. The Talus House is near the upper right corner |

Facilities and Administration

BANDELIER NATIONAL MONUMENT is easily reached by automobile from Santa Fe over 45 miles of road. North of Santa Fe, the first 15 miles are paved, but the next 10 miles are dirt road, and inquiry should be made during inclement weather before attempting the trip. The last 20 miles are over a good dirt road; while the grades are rather steep they present no difficulty to late-model cars. This road traverses the detached section of the monument (Otowi) before reaching Frijoles Canyon.

Bandelier can also be reached by automobile from the north via Espanola, N. Mex.; from the west by a beautiful drive across the Jemez Mountains from Cuba, N. Mex., or from the south by way of Jemez Springs. Inquiries should be made as to road conditions before starting on any of these routes. The nearest bus and airplane termini are at Santa Fe; the Santa Fe Railroad line stops at Lamy, southeast of Santa Fe. Chartered trips may be arranged at Santa Fe.

Entrance to one of the subterranean rooms along the south wall of the canyon |

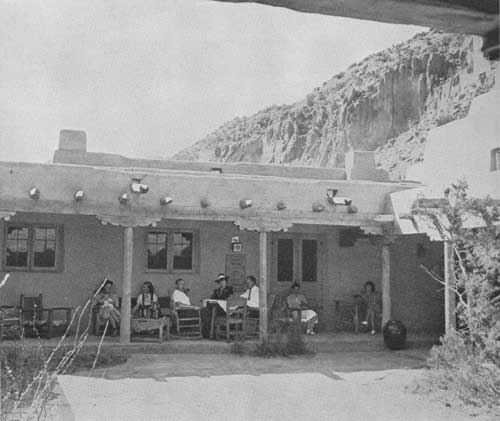

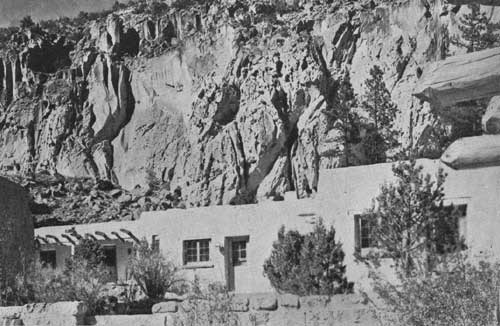

An automobile road, built by the Civilian Conservation Corps in 1935, leads down into Frijoles Canyon to the headquarters area. All the developments are concentrated around a small plaza where the road reaches the bottom of the canyon. A hotel, the Frijoles Canyon Lodge, and the National Park Service administration buildings and museum were all built in the picturesque Santa Fe style of architecture.

The new Frijoles Canyon Lodge, privately operated, furnishes excellent meals and comfortable modern overnight accommodations, and sells gasoline and campers' supplies. It was opened during the 1939 season.

There are 14 cottages, with rates ranging from $1.75 for one person in room without bath to $3.75 with private bath. Rates for two persons range from $2 to $4; for three, $2.50 to $5.50. Meals may be had at 50 to 75 cents for breakfast, 50 cents to $1 for lunch, and 75 cents to $1.25 for dinner; a la carte service is also available.

The National Park Service maintains a large public campground near the headquarters area. Fifty free camp sites are provided, each with tent space, tables and seats, and fireplace. There are also water taps and a number of trailer sites. Free toilet, shower, and laundry facilities are available in a centrally located building.

Adjoining the monument headquarters is the museum. It includes exhibits on the geology and wildlife of the region, the racial and cultural types and divisions of North American Indians, the archeology of Bandelier National Monument, and the ethnology of the modern Pueblo Indians of the Rio Grande region. It also explains the manner in which this information on the ancient Indians has been compiled.

The ceremonials, architecture, methods of making pottery, and other features of the life of the Pueblos are explained by exhibits. The ethnological displays are of special interest to visitors who stop at San Ildefonso or Santa Clara, modern Pueblo villages located near the road to the monument.

A modern youngster in an ancient dwelling |

Other pueblos, many holding regular dances and ceremonials which the public may attend, can be reached from Santa Fe. With recent road improvements, it is relatively easy, except during rainy weather or midwinter, to make Bandelier a stopping-place on a loop drive through the Jemez country or on a trip from Santa Fe or Taos to Chaco Canyon National Monument, Aztec Ruins National Monument, or Mesa Verde National Park.

The National Park Service administers the monument through a full-time custodian who is assisted during the period of heavy summer travel by three temporary rangers.

Regular conducted walking tours of the Frijoles Canyon ruins are offered at scheduled hours; special trips to other points of interest can also be arranged. The regular trip takes about an hour.

The new lodge in the heart of the canyon |

Rules and Regulations

THE PARK SERVICE personnel has the duty of enforcing such regulations as have been prescribed by the Federal Government for the protection of the archeological and natural features of the area, in order that they may be preserved intact for the enjoyment of future visitors. The most important of these rules are:

No hunting is permitted in the monument or picking flowers or damaging plants.

Dogs and cats are permitted only when on a leash.

No disturbance of any prehistoric ruins is permitted, and visitors must be accompanied by a guide when visiting the ruins.

Visitors must not mark or injure any buildings, signs, etc., within the monument area.

The greatest care must be taken with campfires. An entrance fee of 50 cents per car is charged at the monument entrance; it entitles the visitor to admission for the entire calendar year; house trailer and motorcycle fee, 50 cents annually.

Requests for further information, or other correspondence concerning Bandelier National Monument, should be sent to Custodian C. A. Thomas, Bandelier National Monument, Box 669, Santa Fe, N. Mex., or to Superintendent Hugh M. Miller, Southwestern National Monuments headquarters, Coolidge, Ariz.

A corner of the lobby of the lodge |

References

BANDELIER, A. F. A., The Delight-Makers, Dodd, Mead and Co., New York, 1890 (second edition, 1918). An ethno-historical novel about the prehistoric people of Frijoles Canyon.

FERGUSSON, ERNA, Dancing Gods. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 1931. Excellent popular book on ceremonies of the Southwestern Indians.

HENDRON, J. W., Jr., Frijoles Prehistory. A full and detailed report on the 1937 archeological work of the National Park Service, to be published soon.

HEWETT, EDGAR L., Ancient Life in the American Southwest. Bobbs Merrill Co., Indianapolis, 1930. A very readable popular book, inaccurate occasionally.

HEWETT, EDGAR L., The Pajarito Plateau and its Ancient People. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1939. Same comment.

KIDDER, A. V., Introduction to Southwestern Archaeology. Yale University Press, New Haven, 1924. The standard work on the Pueblo area in general.

MERA, H. P., Ceramic Clues to the Prehistory of North-Central New Mexico, Laboratory of Anthropology, Santa Fe, 1935. Highly technical and detailed, very important.

UNDERHILL, RUTH, First Penthouse Dwellers of America, J. J. Augustin, New York, 1938. Extremely readable popular book on the modern Pueblo Indians.

The guest cabins of the lodge, with every modern convenience, offer a great contrast to the ancient cliff dwellings viewed from the windows |

Looking east from the Talus House in the foreground, the road leading down into the canyon can be seen |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1941/band/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010