|

GETTYSBURG

Guidebook 1940 |

|

Gettysburg National Military Park*

THREE MONTHS and sixteen days after the ordeal of arms had receded southward and quiet had returned to the surrounding Pennsylvania countryside, a tall dark man in sombre dress spoke a benediction of two hundred and seventy-two words, in a newly established national cemetery, over the spirits of the dead who had fallen at Gettysburg.

These words were spoken by a man whose invitation to speak at the dedication services was "an afterthought" on the part of those who planned the event. The invitation sent to him six weeks after Edward Everett had been invited to deliver the address of the occasion asked that he set aside the grounds "by a few appropriate remarks." It came only after the man himself had indicated his intention of being present following his receipt of a printed invitation similar to those mailed to all members of Congress, members of the Cabinet, members of the Diplomatic Corps, and other ranking officials.

Twenty-three days had elapsed since the first bodies of the fallen dead had been given final resting place in the national cemetery when the words the world noted little but remembered long fell on the historic landscape and gave a conclusion of sublimity and pathos to a momentous event.

Lord Curzon in his Cambridge University lectures declared that the three "supreme masterpieces" of English eloquence were the toast of William Pitt after the victory of Trafalgar, and two of Abraham Lincoln's speeches, the Second Inaugural and the Gettysburg Address.

The meaning of the battlefield of Gettysburg for the American of today is perhaps best comprehended by recalling the classic prose which was inspired by, and bears the name of, the greatest contest of arms on American soil.

|

LINCOLN'S GETTYSBURG ADDRESS Fourscore and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal. Now we are engaged in a great Civil War, testing whether that nation, or any nation so conceived and so dedicated, can long endure. We are met on a great battlefield of that war. We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that that nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this. But, in a larger sense, we cannot dedicate—we cannot consecrate—we cannot hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract. The world will little note, nor long remember what we say here, but it can never forget what they did here. It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work which they who fought here have thus far so nobly advanced. It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us—that from these honored dead we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave their last full measure of devotion—that we here highly resolve that these dead shall not have died in vain—that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom—and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth. |

GETTYSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK

IN 1895, the battlefield of Gettysburg was established as a national park by act of Congress. In that year, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, which was founded a few months after the battle, transferred its holding of 600 acres of land, 17 miles of avenues, and 320 monuments and markers to the Federal Government. This park was under jurisdiction of the War Department until 1933 when it was transferred to the Department of the Interior to be administered by the National Park Service. Today, the Government owns approximately 2,300 acres of land and maintains 25 miles of paved roads in the park. The field over which the battle was fought covers about 16,000 acres and includes the town of Gettysburg. A total of 2,388 monuments, tablets, and markers have been placed along the main battle lines, and 417 cannon are located on the field in the approximate position of the batteries during the battle.

The Gettysburg National Cemetery was turned over to the United States in 1872 for administration by the War Department. The first burials, however, were made here shortly after the battle when the Union States purchased land on which to inter their dead. Until the burial ground was transferred to the Federal Government, it was administered as the Soldiers' National Cemetery by representatives appointed by the Governors of the Northern States. In the cemetery are buried 3,604 Union soldiers, 979 of whom are listed as unidentified. Here also is located the monument which marks the spot where Lincoln delivered the Gettysburg Address.

In the program of restoration and preservation at Gettysburg National Military Park the Civilian Conservation Corps has made an important contribution. The Corps has participated in the construction of roads, parking areas, foot trails, historic fences, the repair of buildings, and in general landscaping.

Information concerning the park may be secured in the park office in the Post Office Building in Gettysburg, at the park entrance stations, or by addressing the Superintendent, Gettysburg National Military Park, Gettysburg, Pa. An official guide service operates under the supervision of the superintendent of the park.

|

THE CAMPAIGN AND BATTLE OF GETTYSBURG

THE Battle of Gettysburg was one of the truly decisive battles of world history. Here the Confederate Army, commanded by its greatest general and great spiritual leader, Robert E. Lee, made its supreme endeavor in attempting to destroy the Army of the Potomac on its own soil. Here the Union Army stood firm in its purpose to preserve the Nation united, and turned back the supreme Confederate onslaught.

The military spirit of the Confederacy was at "high noon." Important victories at Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville had given new life and hope to the South. Discontent with military and public policies was abroad in the North, and an overwhelming defeat of the Union Army on northern soil might serve to sever the strained ties holding the Northern States to the purpose of the war. The mere presence of the Confederate Army in the North might enable the Confederacy to open negotiations with Lincoln on the basis of a recognition of southern independence. Demands for peace in New York State, threats of secession in the Ohio Valley, open opposition to the Federal conscription law, and a serious loss of confidence of the financial leaders and the public in Government investments plainly indicated a nearly demoralized public spirit in the North.

|

|

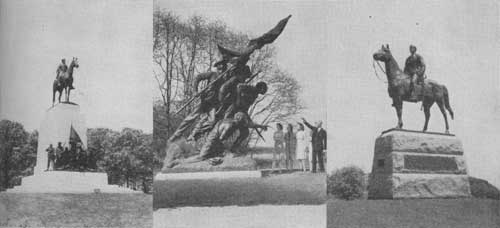

The Virginia Memorial, surmounted by the equestrian statue of Gen. Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate forces at Gettysburg, is one of the most impressive and majestic monuments in the park (left) The North Carolina Memorial at Gettysburg was erected in 1929. This magnificent piece of military sculpture represents a group of soldiers, who, charging across the field, have found momentary shelter in a clump of trees. Foremost is an experienced soldier, and immediately behind him a young man fearfully facing his first battle, receiving counsel from an older man to his left. In the rear is the color bearer. The man on his knees, wounded and fallen, is an officer pointing out the enemy and urging his men forward (center) The equestrian statue of Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, commander of the Federal forces at Gettysburg, faces west from Cemetery Ridge looking out over the field of battle toward the Virginia Memorial on Seminary Ridge (right) |

In the South also there was discontent. It was rising in Virginia, Georgia, and North Carolina over the effects of the blockade. Northern superiority in war supplies and manpower would inevitably decide the war unless the blockade of food and war supplies could be broken. But in June 1863 a marked military victory might not only secure the intervention of Great Britain in behalf of the South, but also go far toward the overthrow of the Federal Government.

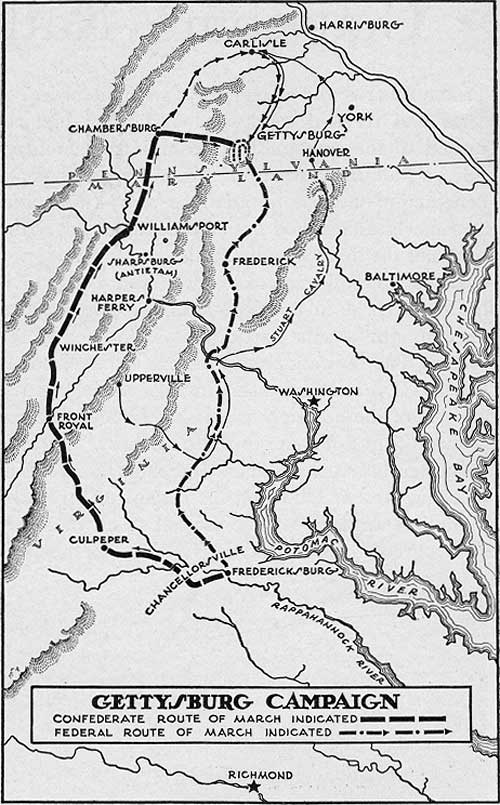

Lee's objective in the campaign that resulted in the Battle of Gettysburg was similar to that of his invasion northward in September 1862, which culminated in the Battle of Antietam. His plan was to destroy the bridge over the Susquehanna River at Harrisburg, disable the Pennsylvania Railroad, sever communications with the West, and, if possible, capture Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington.

On June 3, 1863, Lee began the movement of his troops westward from Fredericksburg, Va., where complete reorganization of his army had resulted in the formation of three infantry army corps commanded by Longstreet, Ewell, and A. P. Hill, and a cavalry division commanded by J. E. B. Stuart. The reorganized Army of Northern Virginia was greatly different from what it had been a few months earlier in at least one important respect. It no longer had "Stonewall" Jackson to act as the right hand of Lee, and in the words of the latter "the finest executive officer the sun ever shone on." The cutting edge of the Confederacy had been dulled by the death of this brilliant soldier following the Battle of Chancellorsville.

Using the Shenandoah Valley as an avenue of approach into Pennsylvania, Lee's army, on June 23, 24, and 25 crossed the Potomac at Williamsport and Shepherdstown into the Cumberland Valley of Maryland and Pennsylvania. The right flank of his army was protected and his action was screened by the Blue Ridge Mountains, with Confederate cavalry constantly occupying the passes.

Gen. Joseph Hooker, in command of the Union Army at Falmouth on the north bank of the Rappahannock in Virginia, was convinced by June 10 that a movement into Maryland of strong Confederate forces was under way, and the Federal forces were put in motion to follow. Thus, unknown to Lee, the Army of the Potomac was also moving northward, on a parallel line, but east of the mountains. In response to Lincoln's command, Hooker was keeping his force between the Confederate force and Washington.

The two great armies moved northward. That they must fight was almost certain; the time and place were not. Actually, the armies were to meet before either of the commanders so intended and were to fight on ground which neither would have chosen.

Unforeseen circumstances between June 25 and June 29 deprived Lee of nearly every advantage he expected to gain in his daring march up the Shenandoah and Cumberland Valleys. Stuart, the incomparable cavalry commander, had obtained conditional approval from Lee to operate against the rear of the Union Army, then pass between that army and Washington to join Lee north of the Potomac. Stuart was delayed in his efforts and did not again get into contact with Lee until July 1. Deprived of his cavalry, Lee was not kept informed of the movements of the enemy.

This reproduction of a Brady photograph, taken immediately after the battle, shows Gettysburg in 1863, then a town of about 2,000 inhabitants, in whose streets hundreds were killed and wounded. Thousands of Union troops were captured here during the afternoon of July 1 as the Federal forces were driven in confusion through the town toward Cemetery Ridge where they found safety and reformed their lines as evening fell. Gettysburg remained in the possession of the Confederates during the battles of July 2-3 |

On the night of June 28 Meade, who was in Frederick, received a message, delivered from Washington, announcing that he had been placed in command of the Army of the Potomac. General Hooker, having been refused authority from Washington to use the garrison at Harper's Ferry with the Union Army, had asked to be relieved of command. On the same night a secret Confederate agent brought to Lee at Chambersburg, Pa., the information that should have been furnished some days earlier by Stuart's cavalry—that the Federal Army was three marches north of the Potomac, and concentrated at Frederick, Md.

This view of Spangler's Spring, taken in the 1890's, shows it essentially as it was during the battle. The area surrounding the spring was occupied by Union troops on the night of July 1, passed to Confederate control on the night of July 2, and was regained by Union troops on the morning of July 3. With this site are associated many acts of magnanimity and deeds of valor |

Lee at once altered his plans. He realized immediately that his extended lines of communications were threatened and that he must concentrate his army. The following day, June 29, the Confederate Army moved eastward, instead of continuing the movement toward Harrisburg, and by June 30 was moving to concentrate at Cashtown, east of the mountains. In the intervening two days since he had assumed command of the Federal forces Meade had moved the troops northward and had instructed his engineers to survey a defensive battle position at Pipe Creek, near Taneytown in northern Maryland, and had sent Buford to make a reconnaissance in the Gettysburg area.

Neither commander yet foresaw Gettysburg as a field of battle. Each expected to take a strong position and force his adversary to attack. A chance engagement of detached troops on the ridge a mile west of Gettysburg was to bring the two great armies together.

THE ARMIES CONVERGE ON GETTYSBURG

On June 30 Buford's cavalry reached Gettysburg and encamped on McPherson Ridge, a mile west of the town, with pickets thrown out far in advance. There he encountered a Confederate force approaching Gettysburg in search of a store of boots which mistakenly were thought to be there. Early the next morning Buford's pickets were driven in by Confederates who desired to test the strength of the Federal forces at Gettysburg, but who did not intend to bring on a general engagement. This chance engagement was to lead to a series of events following in rapid succession, until both armies by forced marches had concentrated at Gettysburg and were engaged in deadly battle. Buford reported to Meade that he was certain a large Confederate force was advancing from the west. Gen. John F. Reynolds, commanding the Union left wing, arrived at Gettysburg about 9 o'clock in the morning of July 1. After a short conference with Buford in the Seminary Building, Reynolds sent an orderly urging a division of Federal troops, advancing across the fields from Emmitsburg Road, to double-quick pace. Upon their arrival about 10 o'clock, while busy directing their movement in McPherson Woods, Reynolds was struck by a Minié ball and killed instantly. The death of Reynolds was a heavy blow to the Union cause, for Meade had lost in him his best corps commander in the very first fighting at Gettysburg.

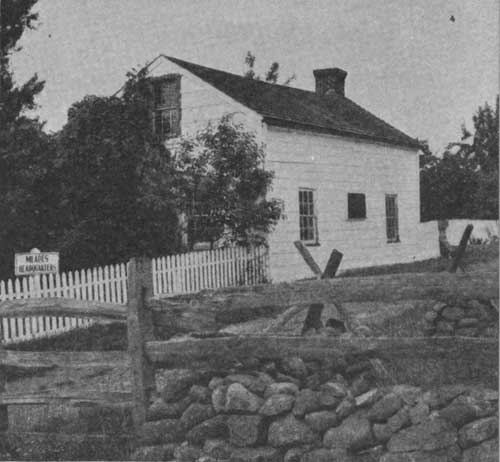

General Meade arrived on the field of Gettysburg near midnight, July 1, and established headquarters in this house, 300 yards in the rear of Cemetery Ridge. In the east room, at a council of war at midnight of July 2, General Meade and the Union Corps commanders determined to continue the battle and to hold the positions they had established |

In the meantime, Confederate troops in force were approaching Gettysburg from the north and northeast. By early afternoon they were engaged with Federal troops who had come up and moved through Gettysburg to a line north of the town.

General Early's opportune arrival in midafternoon with his division, by way of the Harrisburg Road, caught the Union troops in flank and rear at the same time that they were hotly engaged in front and threw them into disorder. No troops could have maintained themselves under such circumstances. A rout soon ensued as the Union line broke and the distressed troops poured back into the streets of Gettysburg. Here thousands of them were captured.

As the Union line north of Gettysburg fell back, the right flank of the Federal line on Oak Ridge was exposed and the division posted there forced to retire. The retreat of the Union troops from the north and northwest left the position on McPherson Ridge untenable and the First Army Corps was forced to relinquish its position. By 4 o'clock in the afternoon, after strenuous resistance, the Union troops had withdrawn to Cemetery Hill, which had been selected in advance as a rallying point in the event that the positions west and north of the town could not be held.

A momentous decision now had to be made. Lee, reaching the field at 3 o'clock in the afternoon, witnessed the headlong retreat of the disorganized Union troops through the streets of Gettysburg, and watched them in their desperate attempt to reestablish their lines on Cemetery Hill. Sensing his immense advantage, he sent orders to Ewell by a staff officer "to press those people and secure the hill [Cemetery Hill] if possible." Two of Ewell's divisions, Early's and Rhodes', were tired after the heavy fighting of the afternoon and not well in hand; Johnson's division could not reach the field until late in the evening. Ewell, uninformed as to the Union strength in the rear of the hills south of Gettysburg and not accustomed to the use of discretionary orders such as Lee was wont to give Jackson, decided to await the arrival of his rear division which was then approaching from Cashtown. Cemetery Hill was not attacked, and Johnson stopped at the base of Culp's Hill. Thus passed Lee's great opportunity of July 1.

THE GETTYSBURG TERRAIN

The quiet little college town of Gettysburg lies in the heart of a fertile country, surrounded by broad acres of crops and pastures, with the substantial homes of industrious Pennsylvania farmers dotted here and there beside dusty country roads or the shady banks of rambling streams. Half a mile west of the town the ground ascends gradually to the elevation of Seminary Ridge, which stretches north and south for several miles. Its name is derived from the Lutheran Seminary standing upon its crest, just south of the Chambersburg Pike.

South of the town and hardly more than a musket shot from the houses on its outer edge, Cemetery Hill rises somewhat abruptly from the lower grounds. Another long roll of land, called Cemetery Ridge, parallel to the one on which the Seminary stands and at an average distance of about two-thirds of a mile east of it, runs south for a mile and a half from Cemetery Hill. It sweeps upward to the wooded crest of Little Round Top, and then goes on for another half mile to terminate in the sugar-loaf peak of Big Round Top, the highest point in the vicinity of Gettysburg. In 1863, nine roads radiated from Gettysburg, the one leading to Emmitsburg going diagonally across the valley between Seminary and Cemetery Ridges.

Although the Battle of Gettysburg began on July 1 west and north of the town, the Union troops before evening were driven from that ground. They fell back upon Cemetery Ridge and the hills north and south of it. This strong and compact position, about 3 miles in length, was in the form of a fishhook, with the point at Spangler's Spring, the hook curving around Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill, the shank lying along Cemetery Ridge, and the eye at Big Round Top. Here the Union Army on July 2 and 3 stood in a semicircle, any part of which, if threatened, could be reinforced promptly by interior lines from any other point.

The Confederates were attacking this position from an exterior semicircle nearly 5 miles long, extending from a point on Seminary Ridge west of the Round Tops around through Gettysburg to a point northeast of Culp's Hill. Although outnumbered on the first day, the Federals on the second and third days, with about 80,000 men as against 75,000 Confederates, had a slightly superior force.

View looking north from Little Round Top, the key position in the Battle of Gettysburg. On July 2 as a fierce Confederate attack was unfolding along the left of the Union line, General Warren, whose statue appears in the left foreground, recognizing the supreme importance of this vital position, rushed Federal soldiers to its height as Confederate troops were scaling its southern slopes. After a desperate hand-to-hand struggle this position remained in Union possession. Warren's quick action in seizing Little Round Top on July 2 was one of the decisive events of the battle |

SECOND DAY AT GETTYSBURG

Early in the afternoon of July 1, Meade learned of the battle that was developing at Gettysburg and of Reynolds' death. A large portion of his army was within 5 miles of Gettysburg and as the news reached him at Taneytown, Hancock arrived with the Second Corps. Meade sent Hancock to Gettysburg to study and report on the situation. Hancock reached the field of battle just as the Federal troops were falling back to Cemetery Hill. He assisted General Howard in rallying the troops and in preparing to hold the hill. Hancock believed there was no need for further retreat and at 6 o'clock left to report to Meade that, in his opinion, the battle should be fought at Gettysburg. Meade acted on his recommendations and immediately ordered the concentration of the Federal Army at Gettysburg. At 2 o'clock in the morning of July 2, Meade arrived on the battlefield and established his headquarters in a little farmhouse just back of Cemetery Ridge.

Longstreet urged Lee to swing around the Union left at Round Top, and, by interposing between the Union Army and Washington, to dislodge Meade, select a good position, and force Meade to make the attack. Lee observed, however, that while the Union position was one of great strength, if held in sufficient numbers to utilize the advantage of interior lines, it presented grave difficulties to a weak defending force. A secure lodgment on the shank of the hook would expose the rear of the troops occupying the hook. Not all of the Union Army corps had reached the field, and Lee perceived the opportunity of destroying his adversary in the process of concentration. He resolved to send Longstreet against the Federal left on the shank, while Ewell was to storm Cemetery Hill and Culp's Hill.

Only intermittent fighting took place on the morning of July 2 while the Confederate command attempted to coordinate its attack. About 3 o'clock in the afternoon the Confederates were massed on the Federal left where General Sickles, contrary to orders and acting on his own initiative, had moved his troops into position in the Peach Orchard and along the Emmitsburg Road. The Round Tops were undefended. The Union left was in great danger. Confederate batteries soon opened fire on the troops in the Peach Orchard and then the Confederate attack was unleashed, sweeping in echelon along the advanced position of Sickles, and spreading the theater of destruction to Big and Little Round Tops, Devils Den, and the whole Federal left. Four hours of desperate struggle broke the Peach Orchard salient, left the Wheatfield strewn with dead and wounded, and the base of Little Round Top a shambles.

THE CRISIS

As soon as the Confederate attack under Longstreet began on the Federal left, Meade sent Gen. G. K. Warren, his chief engineer, to examine the positions at the extreme left. Warren passing rapidly along the line "found Little Round Top, the key to the position, unoccupied except by a signal station." The Confederates lay concealed, awaiting the command for assault, "when a shot fired in their direction caused a sudden movement on their part which, by the gleam of reflected sunlight on their bayonets, revealed their long lines outflanking the position." Immediately comprehending the danger Warren sent posthaste for help. Noticing the approach of some troops, he rode to meet them and caused "Weed's and Vincent's brigades and Hazlett's battery to be detached . . . and hurried them to the summit. The passage of the six guns through the roadless woods and amongst the rocks was marvelous. Under ordinary circumstances it would have been considered an impossible feat, but the eagerness of the men . . . brought them without delay to the very summit, where they went immediately into battle. They were barely in time," for the Confederates were climbing the hill. A desperate hand-to-hand struggle ensued, which ended with Little Round Top, that strategical stronghold, the possession of which controlled the fate of armies, in Union control. Weed and Hazlett were killed, and Vincent was mortally wounded—all young men of great promise.

Ewell, on Lee's left, had been instructed, upon hearing Longstreet's guns, to attack Culp's Hill and Cemetery Hill. The signal had not reached Ewell and it was only at 4 o'clock that his guns opened a belated fire. At dusk the infantry advanced, and moving to attack on the southern slope of Culp's Hill in the area of Spangler's Spring, found the Union earthworks thinly manned. The two Federal divisions stationed here had been called to the aid of their hard-pressed comrades on the Federal left, and the Confederates, finding the position weakly defended, took possession of the earthworks, but did not press the attack beyond in the direction of the Baltimore Pike where lay the Union supply trains. Simultaneous with the attempt against Culp's Hill, Early attacked East Cemetery Hill. Seldom, if ever, surpassed in its dash and desperation, Early's assault reached the crest of the hill where clubbed muskets, stones, and rammers were used in the hand-to-hand struggle. In moving from the streets of Gettysburg Confederate troops, under Rodes, encountered delays and failed to synchronize their attack with Early's. Long after sunset a bright moon illuminated the field of battle. At 10 o'clock the Confederates desisted; the Union troops stood firm.

Devils Den, situated at the left of the Union position, was captured by the Confederates in the fierce fighting of July 2. Thereafter from crevices and natural loopholes in this rocky fastness Confederate sharpshooters picked off Union officers, and engaged in a duel with Federal sharpshooters on the slopes of Little Round Top. After the battle Confederates were found dead here without a wound, apparently killed by the concussion of shells exploding among the rocks |

The High Watermark Monument marks the site of the greatest advance made by the Confederates against the Union position at Gettysburg, reached at the climax of Pickett's charge, and represents a turning point in the course of the war |

THE THIRD DAY

Night of the second day of battle brought an intermission to the bloody combat, but there was no time for rest. What would Meade do? Would the Federal Army remain in its established position and hold its lines at all costs? In a notable Council of War in the east room of Meade's Headquarters near midnight of July 2, at which the corps commanders, Gibbon, Williams, Sykes, Newton, Howard, Hancock, Sedgwick, and Slocum were present, it was determined to hold the positions established.

On the second day Lee had attacked the left and right flanks of Meade's line, and Wright's brigade had broken the Union line just south of the Angle, leading Lee to believe that this was a vulnerable point. The advantageous position along the Peach Orchard and Emmitsburg Road gained on the second day would enable Longstreet's artillery to be brought up from Pitzer Woods and render strong support to an assaulting column.

Again passing over Longstreet's suggestion of enveloping the Union left flank, Lee, encouraged by partial success, determined to renew the conflict on the third day with the general plan unchanged. A feint would be made against the Federal left in the vicinity of the Round Tops. Ewell's troops would attack the Federal right around Culp's Hill, and if the main attack should be successful and Meade compelled to retreat, they were to cut that part of the Federal Army to pieces. In the meantime the flower of the Confederate Army would be hurled at the left center of the Union line in an effort to break through along the shank of the fishhook. Then the entire Confederate force was to assist in destroying the isolated sections of the Union Army. Long lines of artillery had been advanced during the night to the Emmitsburg Road. Numerous batteries now extended northward across the Codori Fields and along Seminary Ridge to the Seminary. Pickett's division of 4,800 men, which had reached the field late on July 2, was to be the spearhead of this desperate attack of more than 15,000 troops on the center of the Union line.

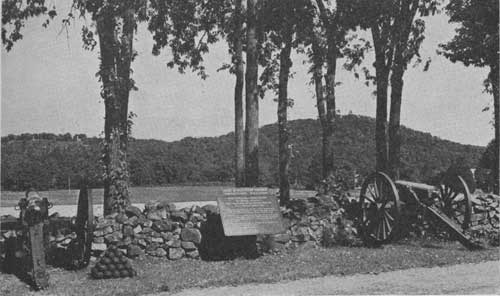

This view shows Big and Little Round Top as seen from the position from which the Confederates moved to launch their fierce attack on Little Round Top and the Union line from Devils Den to the Peach Orchard and the Emmitsburg Road on July 2. Over 400 guns are mounted in the park in approximate positions occupied by artillery during the battle |

Dawn of the third day broke with the thunder of Federal guns on the right in the area of Spangler's Spring and Culp's Hill. Geary's and Ruger's divisions had returned during the night to reoccupy their earthworks in that area. Arriving at the Baltimore Pike, they learned that Confederates had taken this ground. At daybreak, they opened fire and soon made of the meadow below the Spring and the hilly ground above a scene of carnage. Seven hours of furious fighting found the Union troops again in possession of their earthworks. Spangler's Spring, whose cool waters had for a time served Confederate wounded and thirsty, had again become a Union possession.

With the struggle ended at Spangler's Spring, comparative quiet followed, except for casual skirmishing, the intermittent sniping of sharpshooters, and the burning of the Bliss farm buildings west of Ziegler's Grove between the main battle lines. As the silence became extended, it grew more ominous. Presently, at 1 o'clock, two guns of Miller's battery, posted near the Peach Orchard, opened fire in rapid succession. It was the signal for the 138 Confederate guns, in line from the Peach Orchard to the Seminary, to let loose their terrific blast. Union gunners responded with 80 guns, supported by strong reserves. The diminishing ammunition supply of the Confederates led Alexander, commanding Longstreet's artillery, to seek the first opportunity to stop firing and to make way for the infantry charge. After an intensive artillery duel of nearly two hours, Union fire slackened; Meade had ordered a cessation of fire for the cooling of guns and the replacement of others disabled. Thinking the moment opportune, Alexander signaled for the Confederate advance and Pickett's columns started forward in one of the most famous charges in military history.

With the divisions of Heth and Pender on the left and the brigades of Wilcox and Perry on the right, Pickett's division, in magnificent array, emerged from the woods in three successive lines, passed momentarily from sight in an undulation of the ground, and reappeared in one charging mass. Heavy smoke overhanging the field obscured their objective. As the men neared the Codori farm buildings, Pickett realized that his line was too far southeastward. He ordered the troops to turn left and head for the Angle. Wilcox and Perry on his right did not receive the instruction. A break in the line occurred and Stannard's Vermont brigade drove into the opening. From the front and flank fire, the advancing lines crumbled, reformed, and pressed ahead again under terrific fire from Union batteries. At close range double canister and concentrated infantry volleys cut them down in masses. At the peak of the attack General Armistead fell at the moment when, with a hundred men, he had momentarily pierced the Union position at the Angle on Cemetery Ridge. Remnants of the divisions of Pickett, Heth, and Trimble staggered back toward Seminary Ridge, hundreds dropping under the continued fire. Here, at the High Water mark, "the tide of the Confederacy swept to its crest, paused and receded."

The Eternal Light Peace Memorial, constructed from funds contributed by seven States at a cost of $60,000, and dedicated July 3, 1938, is built of Alabama limestone and Maine marble and commemorates "Peace Eternal in a Nation United." The flame in the urn at the top is fed by natural gas carried by mains from western Pennsylvania |

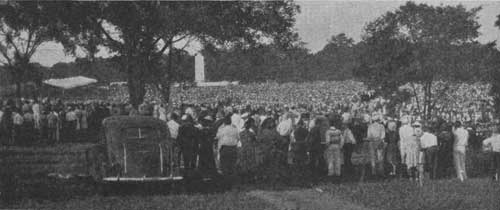

At the time of the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Battle of Gettysburg and of the Reunion of Confederate and Union Veterans, July 1-4, 1938, nearly 8,000 participants in the Civil War were still living. Of these, 1,845 attended the reunion. Union and Confederate veterans are here shown clasping hands across the stone wall at the Angle |

As the strength of Lee's mighty effort at the Angle was ebbing, and the scattered remnants of his troops sought shelter, acts of valor were taking place on another field not far distant.

Lee had counted on the support of Gen. J. E. B. Stuart, whose cavalry had reached the Gettysburg area from Carlisle on the afternoon of July 2. On the morning of July 3, Stuart was ordered to move by the east and southeast of Gettysburg and to attack the rear of the Union center in coordination with Pickett's attack on the Union front. Stuart never reached the rear of the Union lines. He was intercepted by Gregg's and Custer's Union cavalry on a field three miles east of Gettysburg. Faced with the gallant and driving attack of Custer's brigades and of the Third Pennsylvania Cavalry, Stuart found his way blocked and his hope of carrying the aid of his cavalry to Lee frustrated.

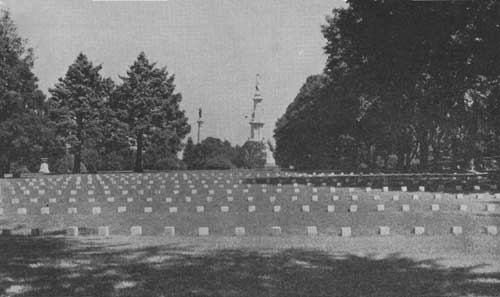

The Soldiers' National Cemetery at Gettysburg was dedicated on November 19, 1863. It was on this occasion that Abraham Lincoln delivered the "Gettysburg Address" from the spot marked by the monument seen in the center background of the photograph. In the burial plot there are 3,604 graves, 979 of which were marked as of unknown dead |

THE RETREAT

The final great effort of the Confederacy at Gettysburg had spent itself. With self-composed dignity, Lee, whose thoughts at this moment may have anticipated Appomattox, took the failure on himself and began rallying his men on Seminary Ridge. Meade withheld the expected counterattack, and the Battle of Gettysburg was over. The following day, July 4, the armies lay facing each other exhausted and torn. More than 50,000 men were killed, wounded, or missing as a result of the battle. Late in the afternoon Lee began an orderly retreat, the wagon train of wounded, 17 miles in length, moving by way of Greenwood and Greencastle, guarded by cavalry. During the night the Confederates moved over the Hagerstown Road, by way of Monterey Pass, to the Potomac, over roads which had become nearly impassable from the heavy rains of July 4. So well did Stuart cover the flank and rear that the army reached the Potomac with comparatively little loss. Meade, realizing that the Confederate Army was retreating, sent his cavalry and Sedgwick's Sixth Corps in pursuit and ordered the mountain passes west of Frederick covered. General Lee, having the advantage of the shorter route to the Potomac, reached the river some days ahead of his pursuers, but, owing to a swollen current, was unable to cross. On the 12th of July, Meade's Army confronted the Confederates in line of battle. On the night of the 13th, the river having fallen, Lee, unmolested, crossed the Potomac into Virginia.

A portion of the crowd, estimated at 250,000 people, present on the occasion of the dedication of the Eternal Light Peace Memorial, July 3, 1938, in Gettysburg National Military Park. The dedicatory address was given by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in front of the Peace Memorial, in the center background. The veterans pavilion is at the left |

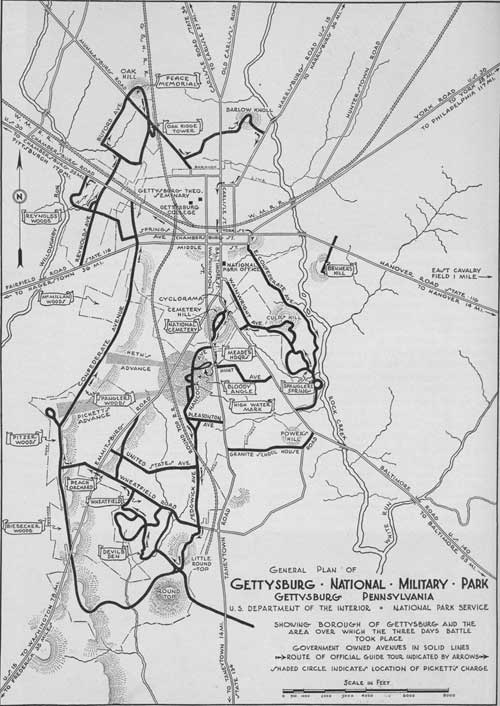

GETTYSBURG NATIONAL MILITARY PARK (click on image for a PDF version) |

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> |

1940/gett/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 20-Jun-2010