|

MOUNT RAINIER

Rules and Regulations 1920 |

|

MOUNT RAINIER NATIONAL PARK.

GENERAL DESCRIPTION.

"OF ALL the fire-mountains which, like beacons, once blazed along the Pacific coast, Mount Rainier is the noblest," wrote John Muir. "The mountain that was God," wrote John D. Williams, giving title to his book.

"Easily King of all is Mount Rainier" wrote F. E. Matthes, of the United States Geological Survey, reviewing that series of huge extinct volcanoes towering high above the sky line of the Cascade Range. "Almost 250 feet higher than Mount Shasta, its nearest rival in grandeur and in mass, it is overwhelmingly impressive both by the vastness of its glacial mantle and by the striking sculpture of its cliffs. The total area of its glaciers amounts to no less than 48 square miles, an expanse of ice far exceeding that of any other single peak in the United States. Many of its individual ice streams are between 4 and 6 miles long and vie in magnitude and in splendor with the most boasted glaciers of the Alps. Cascading from the summit in all directions, they radiate like the arms of a great starfish."

Mount Rainier is in western Washington, about 40 miles due southeast from the city of Tacoma and about 55 miles southeast from Seattle. It is not a part of the Cascade Range proper, but its summit is about 12 miles west of the Cascade summit line, and is therefore entirely within the Pacific slope drainage system.

The Mount Rainier National Park is a rectangle approximately 18 miles square, of 207,360 acres. It was made a national park by act of Congress of March 2, 1899.

The southwest corner of the park, at which is the main entrance, is distant by automobile road 6 miles from Ashford on the Tacoma Eastern Railroad, 56 miles from Tacoma, and 96 miles from Seattle.

Seen from Tacoma or Seattle the vast mountain appears to rise directly from sea level, so insignificant seem the ridges about its base. Yet these ridges themselves are of no mean height. They rise 3,000 to 4,000 feet above the valleys that cut through them, and their crests average 6,000 feet in altitude. Thus at the southwest entrance of the park, in the Nisqually Valley, the elevation, as determined by accurate spirit leveling, is 2,003 feet, while Mount Wow (Goat Mountain), immediately to the north, rises to an altitude of 6,030 feet.

ITS GREAT PROPORTIONS.

But so colossal are the proportions of the great volcano that they dwarf even mountains of this size and give them the appearance of mere foothills. In height it is second in the United States only to Mount Whitney.

Mount Rainier stands, in round numbers, 11,000 feet above its immediate base, is nearly 3 miles high, measured from sea level, and covers 100 square miles of territory, or one-third of the area of Mount Rainier National Park. In shape it is not a simple cone tapering to a slender, pointed summit like Fuji (Fujiyama), the great volcano of Japan. It is rather a broadly truncated mass resembling an enormous tree stump with spreading base and irregularly broken top.

Its life history has been a varied one. Like all volcanoes, Rainier has built up its cone with the materials ejected by its own eruptions—with cinders and steam-shredded particles and lumps of lava and with occasional flows of liquid lava that have solidified into layers of hard, basaltic rock. At one time it attained an altitude of not less than 16,000 feet, if one may judge by the steep inclination of the lava and cinder layers visible in its flanks. Then a great explosion followed that destroyed the top part of the mountain and reduced its height by some 2,000 feet.

Indian legends tell of a great eruption. There have been slight eruptions within memory—one in 1843, one in 1854, and one in 1858, and the last in 1870. Even now it is only dormant. Jets of steam melt fantastic holes in the snow and ice at its summit, and there are hot springs at its foot. But it is entirely safe to visit Mount Rainier, as further eruptions are unlikely.

|

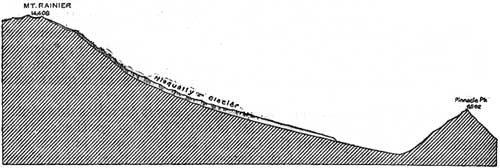

| PROFILE OF MOUNT RAINIER SHOWING NISQUALLY GLACIER. |

SECOND LOFTIEST TO WHITNEY.

Later on this great cavity, which measured nearly 3 miles across from south to north, was filled by two small cinder cones. Successive feeble eruptions added to their height until at last they formed together a low rounded dome—the eminence that now constitutes the mountain's summit. The higher portions of the old crater rim rise to elevations within a few hundred feet of the summit and, especially when viewed from below, stand out boldly as separate peaks that mask and seem to overshadow the central dome. Especially prominent are Point Success (14,150 feet) on the southwest side and Liberty Cap (14,112 feet) on the northwest side.

The altitude of the main summit has for many years been in doubt. Several figures have been announced from time to time, no two of them in agreement; but all of these it is to be observed, were obtained by more or less approximate methods. In 1913 the United States Geological Survey, in connection with its topographic surveys of the Mount Rainier National Park, made a new series of measurements by triangulation methods at close range. These give the peak an elevation of 14,408 feet, thus placing it near the top of the list of high summits of the United States. This last figure, it should be added, is not likely to be in error by more than a foot or two, and may with some confidence be regarded as final. Greater exactness of determination is scarcely practicable in the case of Mount Rainier, as its highest summit consists actually of a mound of snow, the height of which naturally varies.

This crowning snow mound, which was once supposed to be the highest point in the United States, still bears the proud name of Columbia Crest. It is essentially a hugh snowdrift or snow dune heaped up by the furious westerly winds.

A GLACIAL OCTOPUS

One of the largest glacier systems in the world radiating from any single peak is situated on this mountain. A study of the map will show a snow-covered summit with great arms of ice extending from it down the mountain sides, to end in rivers far below. Six great glaciers appear to originate at the very summit. They are the Nisqually, the Ingraham, the Emmons, the Winthrop, the Tahoma, and the Kautz glaciers. But many of great size and impressiveness are born of the snows in rock pockets or cirques, ice-sculptured bowls of great dimensions and ever-increasing depth, from which they merge into the glistening armor of the huge volcano. The most notable of these are the Cowlitz, the Paradise, the Fryingpan, the Carbon, the Russell, the North and South Mowich, the Puyallup, and the Pyramid glaciers.

Twenty-eight glaciers, great and small, clothe Rainier-rivers of ice, with many of the characteristics of rivers of water, roaring at times over precipices like waterfalls, rippling and tumbling down rocky slopes—veritable noisy cascades, rising smoothly up on hidden rocks to foam, brooklike, over its lower edges.

Every winter the moisture-laden winds from the Pacific, suddenly cooled against its sunmit, deposit upon its top and sides enormous snows. These, settling in the crater which was left after the great explosion in some prehistoric age carried away perhaps 2,000 feet of the volcano's former height, press with overwhelming weight down the mountain's sloping sides.

Thus are born the glaciers, for the snow under its own pressure quickly hardens into ice. Through 14 valleys self-carved in the solid rock flow these rivers of ice, now turning, as rivers of water turn, to avoid the harder rock strata, now roaring over precipices like congealed waterfalls, now rippling, like water currents, over rough bottoms, pushing, pouring relentlessly on until they reach those parts of their courses where warmer air turns them into rivers of water.

WEALTH OF GORGEOUS FLOWERS.1

1The most abundant flowers are descrised in the illustrated publication entitled "Features of the Flora of Mount Rainier National Park," which may be obtained from the Superintendents of Documents, Washington, D. C., for 25 cents. It may be puchased also by personal application at the office of the superintendent at the entrance to the park, but that officer can not fill mail orders.

In glowing contrast to this marvelous spectacle of ice are the gardens of wild flowers surrounding the glaciers. These flowery spots are called parks. One will find on the accompanying map Spray Park, St. Andrews Park, Indian Henrys Hunting Ground, Paradise, Summer Land; and there are many others.

"Above the forests," writes John Muir, "there is a zone of the loveliest flowers, 50 miles in circuit and nearly 2 miles wide, so closely planted and luxurious that it seems as if nature, glad to make an open space between woods so dense and ice so deep, were economizing the precious ground and trying to see how many of her darlings she can get together in one mountain wreath—daisies, anemones, columbine, erythroniums, larkspurs, etc., among which we wade knee deep and waist deep, the bright corollas in myriads touching petal to petal. Altogether this is the richest subalpine garden I have ever found, a perfect flower elysium."

The lower altitudes of the park are densely timbered with fir, cedar, hemlock, maple, alder, cottonwood, and spruce. The forested areas, extending to an altitude of about 6,500 feet, gradually decrease in density of growth after an altitude of 4,000 feet is reached, and the high, broad plateaus between the glacial canyons present incomparable scenes of diversified beauties.

| <<< Previous | <<< Contents>>> | Next >>> |

1920/mora/sec1.htm

Last Updated: 25-Aug-2010