CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Montezuma Castle National Monument

As we continue our celebration of the centennial of the National Park Service, this month we explore another important period during NPS history — the era (1933-1942) of the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC). First appearing in the September 1983 issue of CRM Bulletin (Vol. 6, No. 3), John Paige's article introduces us to the significant contributions of the CCC in creating a wide range of visitor facilities in our national (and state) parks. To learn more details about their contributions to the National Park Service, you are encouraged to read The Civilian Conservation Corps and the National Park Service, 1933-1942: An Administrative History (1985), also written by John Paige, along with these additional books. The CCC: It Gave A New Face To The NPSOn March 4, 1933, Franklin Delano Roosevelt took the oath of office as the thirty-second president of the United States. Three and a half years had passed since the Wall Street Stock Market crash of October 29, 1929 triggered the onset of the Great Depression. Roosevelt had promised during the election that he would put Americans back to work and revive the economic life of the nation. Accordingly, in the next one hundred days, Congress passed a variety of relief and economic measures signed by the president. One of these bills created the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) which became one of the most popular of all the New Deal programs.

The intellectual origin of the CCC can be traced back to William James's essay entitled, "The Moral Equivalent of War," published in 1910. James proposed that youth be conscripted for work camps dedicated to performing public service through manual labor. Precedent for such camps came from Europe where, after World War I, work camps were established in France to rebuild those regions devastated by the war. Later, youth work camps were instituted in Italy, Germany, Switzerland, Great Britain, and the Scandinavian countries. President Roosevelt knew of the ideas expressed by James and of the European youth camps. He also believed in the need for conservation of America's natural resources. Five days after his inauguration, he conferred with the Secretaries of Interior, War, and Agriculture, the Director of the Budget, the Army Judge Advocate-General, and the solicitor for the Department of the Interior. During this meeting, the president outlined his plan for placing one-half million men to work on conservation projects under the auspices of the assembled departments. Roosevelt directed the group to draw up the necessary legislation for submittal to Congress. The result was a bill for the relief of the unemployed through the performance of useful public works. The bill quickly passed both houses of Congress and was signed into law on March 31, 1933. Full implementation of the legislation occurred through a series of executive orders beginning with one on April 5 which designated Robert Fechner as the Director of the Emergency Conservation Work (ECW) and officially established the CCC. Fechner and his staff were responsible for the policy and coordination of all ECW programs among the participating agencies. An advisory council consisting of representatives from the executive Departments of Agriculture, Interior, Labor, and War was created to resolve any difficulties arising among agencies and to report on the progress of the various CCC programs. Later, a representative was appointed from the Veterans' Administration to join the advisory council. To efficiently administer the National Park Service (NPS) aspects of the CCC program, NPS Director Horace Albright appointed Chief Forester John D. Coffman to supervise CCC work carried out in NPS areas. He also appointed Conrad L. Wirth, Chief of the Branch of Planning, to administer the ECW within the state parks program, placed under NPS auspices. In 1936, Director Arno B. Cammerer consolidated administration of all CCC programs under Wirth.

The thrust of the CCC program within the NPS was to conserve natural resources, preserve historical and archeological resources, and develop recreational resources within park areas. These goals were accomplished through programs such as fire-fighting, archeological surveys and excavations, ruins stabilization, road and trail conservation, reforestation, erosion control, exhibit building, research and guide services, insect control, campground developments, and construction of recreational facilities. When the state parks program was instituted, few states had any type of parks system. The state parks program sought to accomplish conservation work, recreational development, and preservation work in those areas which would eventually form the nucleus for a state parks system or, if nationally significant, become part of the National Park System. The work undertaken by the state park CCC camps resembled that accomplished by these in the national park areas except that CCC camps received more latitude in developing recreational areas. State park units developed outdoor amphitheaters, created artificial lakes, and constructed swimming pools and other recreational facilities, usually not sanctioned in NPS areas. Among the areas in the state parks program which eventually became part of NPS were Big Bend National Park, San Antonio Missions National Historical Park, Buffalo National River, and Everglades National Park. The first enrollment period for the CCC began on April 1, 1933, and lasted until September 30, 1933. During this period, 70 CCC camps were installed in various state areas under NPS administration. Most of these camps, each consisting of approximately 200 men, became fully operational after May, 1933. The Department of Labor recruited and selected enrollees, while the War Department processed them and supervised the camps. For those camps established within existing park areas and for a few state camps, NPS park superintendents determined project formulation, and supervised the quality of work performed, as well as the project's completion. Prior to each enrollment period, park superintendents submitted project lists to the Washington office for national prioritization. The Washington office then selected these projects to be completed during the next enrollment period. Originally, work estimates in park areas prophesied completion in 20 years; however, the CCC finished all these projects within the first three years of its existence.

Initially, many inside and outside the NPS expressed concern about the CCC program. A number of citizen and business groups objected to the location of the CCC camps near their communities. They called the CCC recruits "tramps," and contended that the CCC presence would result in increased crime, and threaten community stability. These fears proved groundless. The location of camps near towns proved an economic benefit and studies found that little or no increase in crime resulted. Within the NPS, park superintendents felt the CCC program would result in park overdevelopment and in irretrievable losses of natural and cultural resources. Therefore, a system of project review was instituted by which all proposed CCC work was submitted for Washington office approval by landscape architects, engineers, historians, archeologists, and wildlife experts. These professionals judged each project on appropriateness and potential impact on park resources. Through this process, a number of proposed projects were rejected as having adverse impacts upon either natural or historical resources. After the first enrollment period, the Roosevelt Administration decided to continue the CCC program. Quarterly recruiting operations provided a ready pool of applicants for enrollment. The authorized number of camps fluctuated every enrollment period. The NPS operated a larger number of summer camps than winter camps, because a majority of park areas, such as Isle Royale National Park, could be occupied only in the summer months, while a minority, such as Death Valley National Monument, could be used only in winter.

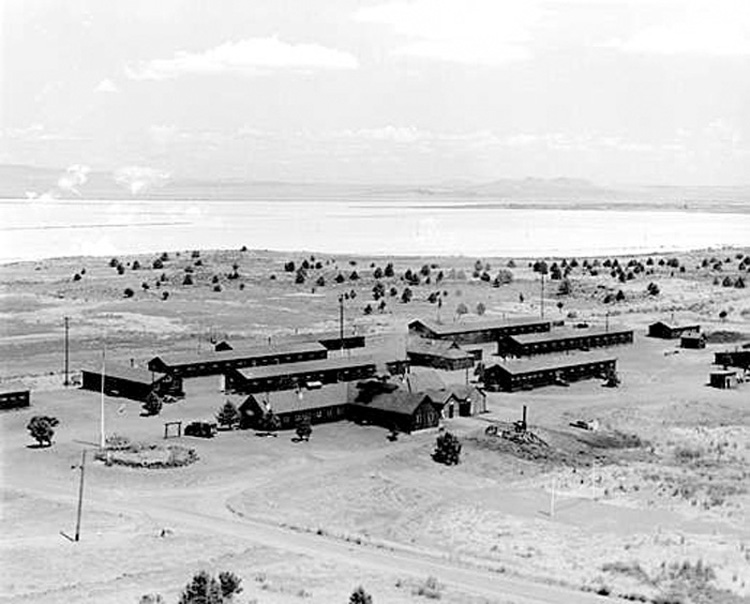

By 1935, the NPS operated camps not only within the United States, but also in the territories of the Virgin Islands and Hawaii. Later, a CCC camp opened at Mount McKinley National Park in Alaska Territory. Besides these traditional areas, the NPS administered the Recreational Demonstration Areas. Such sites were purchased with Resettlement Administration funds and turned over to the NPS for recreational development. Erosion control, drainage, and reforestation were accomplished on the sites, if required, followed by the construction of trails, swimming pools, ski facilities, picnic areas, campgrounds and other recreational facilities. Eventually, most of these areas were turned over to federal, state, county or city governments for continued operation and maintenance. Catoctin and Prince William Forest entered the Service through this program. The Washington office in 1935 organized a separate Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings to direct the comprehensive planning and development needs posed by an expanding NPS historical program after 1933. During the next several years, this branch lacked adequate staffing, and so personnel were hired using ECW funds. Later, many of these temporary jobs were converted to permanent positions. The year of 1935 represented the high water mark for CCC employment by the NPS. In that year, the NPS operated 115 CCC camps in national park areas and administered another 475 camps through the state parks program. At this point, the Roosevelt Administration decided to start phasing out the "temporary" New Deal employment programs. Consequently, a reduction of CCC camps and enrollment was ordered. In 1937, a small expansion in CCC camps and enrollment was allowed, only to be followed by increasing cutbacks by the program. The beginning of World War II in Europe prompted a further reduction in CCC enrollment and the conversion of camps to defense- related projects. This process greatly accelerated in December, 1941, when the United States entered the war. In the next few months, Congress passed a resolution which terminated funding for the CCC after July 1, 1942. During the last enrollment period, only 19 camps operated in national park areas; 70 were administered under the state parks program, with 50 of those on military reservations performing defense-related work.

In less than ten years, the CCC program left an indelible mark on NPS history. Many of the presently existing trails, roads and park facilities in national park areas originated as CCC projects. The corps dramatically developed and altered the national park areas. Today, CCC work is gradually being altered or destroyed, with only scattered examples of this monumental work being preserved. The National Park Service has begun to recognize the historical importance of many of these structures . In the Western Region and to some extent in other regions, an examination of the rustic architecture of CCC construction has already been made. However, a systematic evaluation of CCC contribution to individual parks remains to be accomplished on this fiftieth anniversary of its establishment. |

|||||||