CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Pinnacles National Park

|

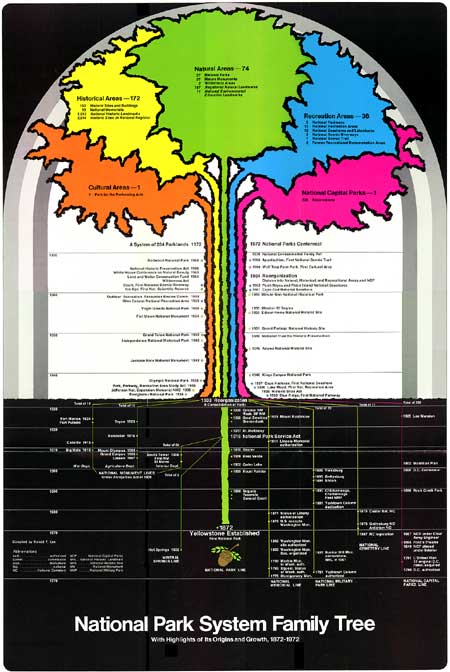

The following National Park System timeline has been extracted from Family Tree of the National Park System written by Ronald F. Lee to commemorate the centennial of the world's first national park — Yellowstone — in 1972. GROWTH OF THE NATIONAL PARK SYSTEM, 1933-1964

The long period between 1933 and 1964, which began with the need to assimilate 71 diverse areas into the System, was crowded with other events also tremendously important to the National Park Service. The early years were marked by the great social and economic changes in American life that accompanied the New Deal. Among many other measures in 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt instituted a broad program of natural resource conservation implemented in large part through the newly created Civilian Conservation Corps but also supported by other emergency funds. At the program's peak in 1935, the Service was allotted 600 CCC camps, 118 of them assigned to National Park System areas and 482 to State Parks, employing approximately 120,000 enrollees and 6,000 professionally trained supervisors, including landscape architects, engineers, foresters, biologists, historians, architects, and archaeologists. The effects of the CCC and other emergency programs on Service management, planning, development, and staffing were profound. Within a few short years, however, came the tragedy of Pearl Harbor, and the nation turned sharply from domestic programs to total mobilization for World War II. Not only was the CCC dismantled with other emergency programs, but regular appropriations for managing the National Park System were cut from $21 million in 1940 to $5 million in 1943, the number of full-time employees was reduced from 3,510 to 1,974 or 55%, and visits fell from 21 million in 1941 to 6 million in 1942. There was only a brief lull after 1945 before military needs again became dominant with the outbreak of the Korean War. During these years the integrity of the System required constant defense against wartime pressures. But peace finally came and the 1950's and early 1960's witnessed a tremendous increase in travel in our affluent postwar society with personal incomes and leisure time steadily increasing for growing numbers of people, most of whom also enjoyed much greater mobility in the automobile age. Visits to the National Park System mounted from a low of 6 million in 1942 to 33 million in 1950, and 72 million in 1960. These and other changing conditions, including a great and growing backlog of deferred park maintenance and development projects, posed vast new problems for the Service and System. It was an era marked by the dramatic inauguration and prosecution of Mission 66, the emergence of a national "crisis in outdoor recreation," creation of the Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission and the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation, and mounting national concern for better preservation of America's vanishing wilderness. These sweeping social, economic, and political changes are far too important, complex and recent for more extended treatment here. We will focus our attention on only one aspect of this period—enlargement of the National Park System. Between the Reorganization of 1933 and the Reorganization of 1964,1 102 areas were added to the System as defined today,2 increasing the total number from 137 to 239. These numerous and diverse areas were established under the able leadership of four successive Directors — Arno B. Cammerer, 1933-1940; Newton B. Drury, 1940-1951; Arthur E. Demaray, 1951 (after serving seventeen critical years as Associate Director to his two predecessors); and Conrad L. Wirth, 1951-64. These four Directors were vigorously supported by successive Secretaries of the Interior and worked closely with many members of Congress to bring about responsible growth of the System. They were aided, too, by an increasingly expert staff whose members, both in Washington and the field, contributed much to this work, including among others, Thomas C. Vint, long-time Chief, Division of Design and Construction; Ben H. Thompson, Chief, Division of Recreation Resource Planning; and Hillory A. Tolson, Assistant Director. The distribution of the new areas among categories is significant. Of the new additions, 11 were Natural Areas, increasing their number from 58 to 69 or 19%. Seventy-five were Historical Areas, increasing their number from 77 to 152 or 96%. Fifteen were Recreation Areas, increasing their number from one to 16, or 1500%. It is clear that during this period the growth rate for Natural Areas noticeably diminished from previous levels and by comparison with the rate for other categories, even though very important additions of natural lands were still being made. On the other hand the growth rates for Historical and Recreation Areas accelerated sharply. It took the Service a generation, from 1933 to 1964, to assimilate these 102 diverse new areas and the 71 areas added by the Reorganization of 1933 and incorporate them securely into one National Park System. During this period, with some exceptions, the Service tended to emphasize the similarities between areas while minimizing their differences. The System was administered under a single, uniform code of administrative policies derived historically from National Park experience and developed primarily for the management of Natural Areas. Special policies particularly applicable to Historical Areas, however, were gradually incorporated into the code—for example, the important restoration policy adopted in 1938. But more than any other factor, it was Mission 66, under the leadership of Director Conrad L. Wirth, that at long last provided the resources, beginning 1956, to bring all the individual areas, regardless of origin or type, up to a consistently high standard of preservation, staffing, and carefully controlled physical development, and to consolidate them fully into one National Park System. Mission 66 generated widespread interest and support for the National Park System among the American people and brought new vigor and momentum to all phases of National Park Service work. 1The precise period meant here is from June 10, 1933, to July 10, 1964, when a new organizational framework was adopted for the National Park System which clearly differentiated between natural, historical, and recreational areas. 2These figures include nine National Historic Sites and one International Park in non-federal ownership and five reservoir-related Recreation Areas established under cooperative agreements. Since Sept. 28, 1966, the Service has counted these areas as units in the National Park System. NATURAL AREAS, 1933 - 1964 Four new National Parks and seven scientific National Monuments were added to the System between 1933 and 1964 and three National Parks were created out of existing reservations, as follows:

During his first seven years in office, President Roosevelt established five scientific National Monuments, three of them very large, without serious difficulty, in the same manner as his predecessors. They were Cedar Breaks, proclaimed in 1933 to protect a remarkable natural amphitheater of eroded limestone and sandstone in southern Utah; Joshua Tree, California, 1936, to preserve a characteristic part — initially 825,340 acres — of the famous Mojave and Colorado deserts; Organ Pipe Cactus, Arizona, 1937, to protect 325,000 acres of the Sonoran desert; Capitol Reef, also 1937, to preserve a twenty-mile segment of the great Waterpocket Fold in southern Utah; and Channel Islands, 1938, to protect Santa Barbara and Anacapa Islands, the two smallest in a group of eight islands off the coast of southern California. Roosevelt's sixth scientific National Monument, however, was another story. Jackson Hole had been talked of as a possible addition to Yellowstone as early as 1892, and from 1916 onward the Service and Department actively sought its preservation in the National Park System. It was John D. Rockefeller, Jr., however, who rescued Jackson Hole for the nation after a visit in 1926 left him distressed at cheap commercial developments on private lands in the midst of superlative natural beauty — dance halls, hot dog stands, filling stations, rodeo grand stands, and billboards in the foreground of the incomparable view of the Teton Range. Rockefeller began a land acquisition program, and in a few years his holdings in Jackson Hole exceeded 33,000 acres, which he offered as a gift to the United States. Meanwhile, however, bitter opposition developed among cattlemen, dude ranchers, packers, hunters, timber interests, and local Forest Service officials who preferred livestock ranches or forest crops to a National Park, county officials who feared loss of taxes, and members of the Wyoming State administration who were politically concerned. When no park legislation had been enacted by 1943, Rockefeller indicated he might not be justified in holding his property, on which he paid annual taxes, much longer. President Roosevelt decided to act and on March 15, 1943, proclaimed the Jackson Hole National Monument, consolidating 33,000 acres donated by Rockefeller and 179,000 acres withdrawn from Teton National Forest into a single area adjoining Grand Teton National Park. Roosevelt's proclamation unleashed a storm of criticism which had been brewing for years among western members of Congress. Rep. Frank A. Barrett of Wyoming and others introduced bills to abolish the monument and to repeal Section 2 of the Antiquities Act containing the President's authority to proclaim National Monuments. A bill to abolish the monument passed Congress in 1944 but was vetoed by President Roosevelt who pointed out in an eloquent message that Presidents of both political parties, beginning with Theodore Roosevelt, had established ample precedents by proclaiming 82 National Monuments, seven of which were larger than Jackson Hole. The proclamation was nevertheless also contested in court, where it was strongly defended by the Departments of Justice and Interior and upheld. Finally, a compromise was worked out and embodied in legislation approved by President Harry S Truman on September 14, 1950. It combined Jackson Hole National Monument and the old Grand Teton National Park in a "new Grand Teton National Park" containing some 298,000 acres, with special provisions regarding taxes and hunting. It also prohibited establishing or enlarging National Parks or Monuments in Wyoming in the future except by express authorization of Congress. This long and bitter controversy marked the end of an era for the National Park Service. Thereafter establishment of large scientific National Monuments by proclamation—commonly done between 1906 and 1943—became almost impossible, not only in Wyoming but elsewhere. Only two scientific National Monuments were established under authority of the Antiquities Act during the next 29 years—Buck Island Reef, Virgin Islands, containing only 850 acres, proclaimed by President John F. Kennedy in 1961; and Marble Canyon, Arizona, containing 25,962 acres proclaimed by President Lyndon B. Johnson on his last day in office. More significantly, President Johnson declined to proclaim a proposed Gates of Arctic National Monument, Alaska, containing 4,119,000 acres; a Mt. McKinley National Monument, also in Alaska, containing 2,202,000 acres adjoining the National Park; and a Sonoran Desert National Monument, Arizona, containing 911,700 acres. After 1943, through its control of appropriations and legislation, Congress largely nullified Presidential authority to establish new National Monuments. The Jackson Hole controversy was accompanied by mounting pressure from various interests, especially in the west, to open up protected natural resources in the National Park System for use during periods of national emergency. This pressure reached new heights during World War II. Timber interests sought permission to log scarce Sitka spruce in Olympic National Park for use in airplane production. Livestock interests sought to reopen many areas to grazing to help food production. Mining interests sought permission to search for copper in Grand Canyon and Mount Rainier, manganese in Shenandoah, and tungsten in Yosemite. The military services requested use of park lands for various purposes. In 1942 the Service issued 125 permits to the War and Navy Departments and the next year an additional 403 permits. Troops were trained in mountain warfare at Mount Rainier, for example, military equipment for arctic use was tested at Mount McKinley, and desert warfare units trained at Joshua Tree. Director Drury, supported by Secretary Ickes, successfully defended the basic integrity of the System in the face of these exceptional pressures while permitting as a last resort only those uses absolutely essential to the prosecution of the war and for which there were no alternative sites. With the end of World War II a new round of threats to the System accompanied the post-war development of river basins in the United States by the Corps of Engineers and the Bureau of Reclamation. The proposed Bridge Canyon Dam on the Colorado River would have created a reservoir flooding all of Grand Canyon National Monument and 18 miles of the National Park; Glacier View Dam on the Flathead River in Montana threatened to flood 20,000 acres of Glacier National Park; Echo Park and Split Mountain Dams on the Green and Yampa Rivers were expected to create large reservoirs inundating long stretches of wilderness canyons in Dinosaur National Monument; and the reservoir behind the proposed Mining City Dam on the Green River, Kentucky, would have periodically flooded the famous underground Echo River in Mammoth Cave National Park. In the face of strong opposition and national controversy, conservation organizations and the Service, generally though not always working together, managed to meet these and other similar threats and bring the System through this period relatively unscathed. In spite of these extraordinary pressures, four new National Parks were established between 1933 and 1964 and three others were created out of existing reservations. Everglades National Park, Florida, was authorized May 30, 1934, to protect the largest subtropical wilderness in North America, now also the third largest National Park, situated in the southeastern United States, long under-represented in the System. Everglades is also a beleagured wilderness threatened by drainage projects, drought, and an international jetport — a testing ground for modern conservation principles. Big Bend National Park, Texas, was authorized in 1935 to protect over 700,000 acres of unique wilderness country along the Mexican border, including the Chisos Mountains and three magnificent canyons in the great bend of the Rio Grande. Olympic National Park, Washington, was established in 1938, over the bitter opposition of timber interests after an ardent campaign by conservationists, strongly supported by Secretary Ickes and President Roosevelt. The park was formed around the nucleus of Mount Olympus National Monument. After a 50-year struggle against power and irrigation interests, lumbermen, ranchers, cattlemen, sheepmen, and hunters, Kings Canyon National Park, California, was finally established in 1940 to protect some 710 square miles of magnificent mountain and canyon wilderness on the west slope of the Sierra Nevada. Virgin Islands National Park, our only National Park in the West Indies, was authorized in 1956 to protect nearly two-thirds of the land mass and most of the colorful off-shore waters of St. John's Island, in the American Virgin Islands. The park owes its existence to the generous support of Jackson Hole Preserve, Inc., and Mr. Laurance S. Rockefeller. Finally, Petrified Forest, Arizona, long advocated as a National Park, became one in 1958 — formed from the National Monument of the same name. The world-famous crater of 10,023 foot Haleakala, on the island of Maui, was made a National Park in 1960 by detaching it from Hawaii National Park and making it a separate reservation. Four previously authorized National Parks were also formally established in this period, including the Great Smoky Mountains in 1934, Shenandoah in 1935, Isle Royale in 1940, and Mammoth Cave in 1941. Until 1943, significant additions were also made to several existing National Monuments, including, among others, 305,920 acres added to Death Valley in 1937, 203,885 acres containing the spectacular wild canyons of Utah's Yampa and Green Rivers added to Dinosaur in 1938, no less than 904,960 acres added to Glacier Bay to provide more land for the Alaskan Brown Bear and other wildlife and protect more glaciers, and 150,000 acres added to Badlands in South Dakota both in 1939. In spite of these achievements, the establishment of large, new Natural Areas became increasingly difficult during this period. Sixty-one of the 64 Natural Areas in the System at the time of the Reorganization of 1964 were originally established or authorized before World War II. It is a more startling fact that of the 23,840,162 acres of Federal land in all the Natural Areas of the System on April 1, 1971, some 22,913,488 acres, or 96%, were contained in National Parks or National Monuments established or authorized before World War II. Congress responded to this and similar realities in other areas of conservation by authorizing creation of the highly significant Land and Water Conservation Fund in 1965, beginning a new era in land acquisition that will be discussed in a later section. Partly because of the increasing difficulty of adding new Natural Areas to the System, the Service launched a Natural Landmarks Program in 1962. Its purpose was to recognize and encourage the preservation of significant natural lands by diverse owners, mostly non-federal, including state or local governments, conservation organizations, and even private persons. It was designed to complement the Service's Registered National Historic Landmarks program inaugurated in 1960. On March 17, 1964, Secretary Stewart L. Udall announced the first seven sites eligible for entry on the new National Registry of Natural Landmarks. They were Mianus River Gorge and Bergen Swamp, New York; Corkscrew Swamp Sanctuary, Florida; Elder Creek and Rancho La Brea-Hancock Park, California; Fontenelle Forest, Nebraska; and Wissahickon Valley, Pennsylvania. With this action another tool was added to those available to the National Park Service to help strengthen environmental conservation in the United States. HISTORICAL AREAS, 1933 - 1964 Seventy-five Historical Areas were added to the National Park System between 1933 and 1964, including nine National Historic Sites and one International Park in non-federal ownership. For purposes of clarity these 75 areas are presented under the nine thematic headings currently used by the National Park Service for Historical Areas:

It is an impressive list. One immediately notes a new national system for classifying historical areas. Instead of such categories as National Military Parks, National Memorials and National Monuments commonly used before 1933, we find new categories based on the principal periods or phases in American history. One of the most important steps taken by the National Park Service to meet its sharply increased responsibilities for historic preservation following the Reorganization of 1933 and passage of the Historic Sites Act in 1935 was adoption of this thematic system of classification. The origin of this concept — so unlike classification systems found in several European countries based primarily on architectural styles — may be traced to the Educational Advisory Committee appointed by Secretary Roy O. West in 1928. That committee, headed by Dr. John C. Merriam of the Carnegie Institution, submitted a number of basic recommendations to the Secretary in January 1929. One of these, developed by the anthropologist member, Dr. Clark Wissler, American Museum of Natural History, read in part as follows:

Dr. Wissler's idea was embraced by a successor body, the Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments, appointed in 1935 under provisions of the Historic Sites Act, and notably by one of its most distinguished members and later its Chairman, Dr. Waldo G. Leland, Director of the American Council of Learned Societies. The concept was further developed and refined by Dr. Verne E. Chatelain, Chief Historian of the Service until 1937, and members of his staff. Originally numbering some 22 themes, it has gradually evolved until today it numbers nine major themes and 43 sub-themes. The importance of the concept lies in its comprehensiveness, providing the historic preservation program with an underlying framework which embraces the entire history of man on the North American continent and envisages historical holdings in the National Park System as preserving and presenting through carefully selected monuments a noble panorama of the full sweep of that history for the benefit and inspiration of the people of the United States. The effect of the thematic approach in broadening representation of historic sites and buildings in the System may be seen in the following table: Historic Sites and Buildings According to Theme

The National Park System started out in 1916 with only two of nine themes represented — Theme I, The Original Inhabitants, and Theme II, European Exploration and Settlement, with four areas each. After the Reorganization of 1933, five themes were represented by three areas or more; but Theme IV, Major American Wars, with 23 battlefields and forts not counting eleven National Cemeteries, was much the most heavily represented, reflecting the War Department's long emphasis on National Military Parks. During the last 35 years, however, the historical branch of the Family Tree has been growing, steadily though unevenly, according to an intelligible thematic pattern reflecting the broad sweep of social, cultural, economic, political, and military history in the United States. Much of this would not have happened without the Historic Sites Act of 1935, a logical follow-up to the Reorganization of 1933. On November 10, 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt invited his friend and neighbor, Major Gist Blair, to give consideration "to some kind of plan which would coordinate the broad relationship of the Federal Government to State and local interest in the maintenance of historic sources and places throughout the country. I am struck with the fact there is no definite, broad policy in this matter [underlining supplied]." Roosevelt asked Blair to talk the matter over with Secretary Ickes, "who in the transfer of government functions has been given authority over national monuments," and observed that legislation might be necessary. Before 22 months had elapsed, through the efforts of many persons including Major Blair and his associates in the Society of Colonial Wars, Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin of Williamsburg Va., Secretary Ickes, Assistant Solicitor Rufus G. Poole, J. Thomas Schneider, Director Cammerer, Chief Historian Chatelain Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, Rep. Maury Maverick of Texas, and others, the Historic Sites Act was conceived, drafted, introduced, considered in hearings, amended, passed, and signed by the President on August 21, 1935. The Act declared "that it is a national policy to preserve for public use historic sites, buildings and objects of national significance for the inspiration and benefit of the people of the United States." This new and greatly broadened national policy has been the cornerstone of the Federal Government's historic preservation program ever since 1935, reaffirmed both in the Act of October 26, 1949, which created the National Trust for Historic Preservation, and in the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966. To carry out the policy, the Act assigned broad powers, duties and functions to the Secretary of the Interior to be exercised through the National Park Service, among them: (1) make a national survey of historic and archaeological sites, buildings, and objects to determine which have "exceptional value as commemorating or illustrating the history of the United States;" (2) acquire real or personal property for the purpose of the Act; (3) contract or make cooperative agreements with states, municipal subdivisions, corporations, associations, or individuals to preserve historic properties. The Act established an Advisory Board on National Parks, Historic Sites, Buildings and Monuments. Soon after its passage the Secretary of the Interior established a Code of Procedure for designation of National Historic Sites and created a Branch of Historic Sites and Buildings headed successively during this period by Chatelain, 1935-37; Ronald F. Lee, 1938-51, the war years excepted; and Herbert E. Kahler, 1951-64. This sweeping legislation had important consequences for the Family Tree. It resulted in establishment of the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings to evaluate all historic sites and buildings thereafter proposed for addition to the System and after 1956 all National Historic Landmarks. It provided legal authority for the Secretary of the Interior to designate National Historic Sites which successive Secretaries exercised during this period to add 18 Historical Areas to the System including the Jefferson National Expansion Memorial, Federal Hall, the Old Philadelphia Customs House, the Home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and the Adams National Historic Site, and to designate nine other National Historic Sites in non-federal ownership. The Act provided a new and stronger legal foundation for the Historic American Buildings Survey and the Inter-Agency Archaeological Salvage Program. It created a national Advisory Board to help guide the entire program. In brief, the Act gave new impetus, scope, and direction to National Park Service participation in a rising national movement for historic preservation in the United States. It may be useful at this point to present a comparative table showing the legal basis for all the Historical Areas now in the System. Of 169 areas shown in the following table, 39 were proclaimed by the President under the Antiquities Act, 28 were designated by the Secretary of the Interior under the Historic Sites Act and 102 were authorized by separate Acts of Congress. Sources of Legislative Authority for Historical Areas*

Of 58 Historical Areas established during the last twenty years, 48 were authorized by individual acts of Congress, only eight were designated by the Secretary, and two were proclaimed by the President. It is clear that since World War II the power of the President or the Secretary to establish Historical Areas by proclamation or designation has, largely under pressure from Congress, almost lapsed into disuse. On the other hand, Congress has consistently supported preservation objectives by enacting more than a hundred measures for the protection of individual historic sites and buildings and has reaffirmed its commitment by enacting the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966 and subsequently supporting it with significant appropriations. Returning to our thematic list, we note that the Service program for preserving prehistoric sites and structures was carried forward very modestly between 1933 and 1964. Six prehistoric areas were added to the System, five of them representing Indian cultures in other geographic and cultural regions than the Southwest where previous emphasis had been placed. They included Indian mound groups in Georgia (Ocmulgee) and Iowa (Effigy Mounds), an ancient Indian quarry in Minnesota (Pipestone), an historic sanctuary and prehistoric site in Hawaii (City of Refuge), and a cave in Alabama (Russell Cave) occupied as early as 6000 B. C. Some of the most important historical additions to the System between 1933 and 1964 are almost lost to sight in this long thematic list. Jefferson National Expansion Memorial was the first National Historic Site established under authority of the Historic Sites Act. More important, its 37 square blocks embraced a key urban area on the historic St. Louis waterfront — the first major effort of the Service, after National Capital Parks, to conserve and develop a large and important urban historic site. Some architectural monuments, including the Old St. Louis Post Office and the Cathedral, have been carefully preserved, but the main feature of the area is the only major national memorial of modern design in the United States, and one of a small number in the world — Eero Saarinen's magnificent stainless steel Arch. In 1948, responding to recommendations of a study commission, Congress authorized another major urban project, the Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia, the most important historical area in the United States, embracing Independence Hall and Square, Congress Hall, Carpenters Hall, and many other sites and buildings intimately associated with the winning of our independence and the establishment of our government under the Constitution. The commission method of analyzing complex urban problems was thereafter adopted for Boston, where it led to authorization of Minute Man National Historical Park in 1959. Recommendations for other Boston sites, including the Bunker Hill Monument, Faneuil Hall, and the Old Boston State House, are still pending today. A commission was also established for New York City, where a remarkable complex of urban monuments was developed during this period, adding Federal Hall, Castle Clinton, Grant Memorial, Hamilton Grange, Theodore Roosevelt's Birthplace, and Sagamore Hill to the previously authorized Statue of Liberty National Monument, whose boundaries were extended to include Ellis Island. Seven Presidents of the United States were honored by the addition of areas to the System during this period, strengthening a trend that continues today. The Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington, D. C., was authorized in 1934, followed in 1935 by Andrew Johnson's Home and Tailor Shop in Greeneville, Tennessee. The Home of Franklin D. Roosevelt at Hyde Park, New York, was designated a National Historic Site in 1944 and his summer home on Campobello Island, Canada, was established as the Roosevelt-Campobello International Park in 1964, owned and administered by a special joint United States-Canadian Commission. The Adams House in Quincy, Massachusetts, became a National Historic Site in 1946. Theodore Roosevelt's Birthplace in downtown Manhattan and Sagamore Hill, his home at Oyster Bay, were given to the United States in 1962. The Grant Memorial was added to the System in 1958 and Lincoln's Boyhood Home in Indiana in 1962. Finally, the White House itself, by authorization of Congress and consent of the President, was made subject to the National Park Service enabling act in 1961. Each area makes its own unique contribution to the Family Tree but considerations of space preclude much further comment. The number of historic sites and buildings representing Westward Expansion increased from 6 to 22 during this period. They include seven early forts extending across the west from Fort Smith, Arkansas, and Fort Davis, Texas, to Fort Union, New Mexico, and Fort Vancouver, Washington. Sites which commemorate the history of westward migration include Cumberland Gap in Virginia-Tennessee-Kentucky, and Chimney Rock near the Oregon Trail in Nebraska, the McLoughlin House, Oregon, Whitman Mission, Washington, and the Homestead National Monument, Nebraska. A beginning was also made in preserving sites representing commercial and industrial history, including Salem Maritime, the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, Hopewell Village, an early ironmaking community in Pennsylvania, and the home and laboratory of Thomas Edison. During this period the historic preservation program was also extended well beyond the boundaries of the National Park System. The Historic American Buildings Survey was the first Service venture of this kind, organized in 1933 upon the initiative of Mr. Charles E. Peterson of the National Park Service in cooperation with officials of the Library of Congress and the American Institute of Architects. Since 1933 the HABS has gathered more than 30,000 measured drawings, 40,000 photographs, and 13,000 pages of documentation for more than 13,000 of the Nation's historic buildings. The HABS has had a deep and pervasive influence on the entire historic preservation movement, enormously benefiting scholarship as well as the preservation and restoration of individual monuments and historic districts. The staff of the National Survey of Historic Sites and Buildings, organized after passage of the Historic Sites Act in 1935, has been the principal originator of professional recommendations to the Director, the Secretary, the Advisory Board, and Congress for the addition of Historical Areas to the National Park System. Beginning in 1960, however, the responsibilities of this Survey staff were greatly extended to include recommendation of an important series of National Historic Landmarks, officially designated by the Secretary of the Interior. On October 9, 1960 Secretary of the Interior Fred A. Seaton announced the first official list of 92 historic sites and buildings eligible for designation as National Historic Landmarks. Almost a thousand Historic Landmarks situated throughout the United States, almost all of them in non-federal ownership, have been designated during the past ten years. The Inter-Agency Archaeological Salvage Program was organized by the National Park Service in 1946 at the request of the Committee for Recovery of Archaeological Remains to coordinate the salvage of irreplaceable pre-historic and historic Indian artifacts from projected reservoir sites in river valleys throughout the United States, before flooding. This program, which has been conducted for a quarter of a century in cooperation with the Smithsonian Institution and universities, museums, and research institutions throughout the country, has enormously deepened knowledge of American prehistory. Officials of the National Park Service joined with other preservationists in 1949 to help launch the National Trust for Historic Preservation, chartered by Congress to further the national historic preservation policy set forth in the Historic Sites Act by encouraging greater public participation by the private sector in preservation work. The Secretary of the Interior is designated by statute as an ex-officio trustee. The National Trust has become the major national focus for citizen sentiment and opinion on historic preservation in the United States. Through these varied means the National Park Service reached out between 1933 and 1964, in accordance with its charter in the Historic Sites Act, to influence historic preservation not only at the national level, but also in States and communities throughout the country. RECREATION AREAS, 1933 - 1964 Between 1933 and 1964 important new terms were added to the National Park Service lexicon—"recreation," "land planning" and "state cooperation." The Service responded to the emerging social and economic forces of the New Deal era, among other ways, by greatly expanding its cooperative relationships with the States, securing enactment of the comprehensive Park, Parkway and Recreation Area Study Act of 1936, and initiating four new types of Federal park areas — National Parkways, National Recreation Areas, National Seashores and Recreational Demonstration Areas. By the end of this period fifteen such areas had been authorized or established under the administration of the National Park Service. Because they had much in common, they were collectively designated Recreation Areas in the Reorganization of 1964.

The origin of Recreation Areas as a category in the National Park System stemmed in important part from widened responsibilities assigned to the Service beginning in the 1930's. A central feature of these new responsibilities was administration of hundreds of CCC camps located in State Parks. The National Park Service had actively encouraged the state park movement ever since Stephen Tyng Mather helped organize the National Conference on State Parks at Des Moines, Iowa, in 1921. It was natural for the Service to be asked to assume national direction of Emergency Conservation Work in state parks when that program was launched in 1933. Fortunately for the Service an exceptional administrator, Conrad L. Wirth, was available to lead this complex nationwide program. It was a large and dynamic undertaking, at its peak involving administration of 482 CCC camps allotted to state parks employing almost 100,000 enrollees on work projects guided by a technical and professional staff numbering several thousand. As Freeman Tilden observes in his valuable book, The State Parks: Their Meaning in American Life, published in 1962, the fruits of CCC work are still an admired feature of state parks throughout the United States. As this program got under way it became painfully evident that in the 1930's most states lacked any kind of comprehensive plans for state park systems. Furthermore, the interrelationship of parks, parkways, and recreational areas was even less understood. Against this background the Service sought comprehensive new land planning legislation. The result was the Park, Parkway and Recreation Area Study Act of 1936. Its purpose was to enable the Service, working with others, to plan coordinated and adequate park, parkway and recreational area facilities at federal, state and local levels throughout the country. In 1941 the Service published its first comprehensive report, A Study of the Park and Recreation Problem in the United States, a careful review of the whole problem of recreation and of national, state, county, and municipal parks in the United States. Interrupted by World War II, Director Wirth arranged for these studies to be resumed with the inception of Mission 66, and a second comprehensive report was published in 1964 entitled Parks for America, A Survey of Park and Related Resources in the Fifty States and a Preliminary Plan. Numerous land planning studies of individual areas, river basins, and regions accompanied and supported these comprehensive reports. The four new types of Federal Recreation Areas added to the System between 1933 and 1964 were generally consistent with recommendations in these studies. Descriptions of these types follow: National Parkways. The modern parkway, fruit of the automobile age, appears to have its origins in the Westchester County Parkways, New York, built between 1913 and 1930. At first, Congress also applied the idea locally — in the District of Columbia — but later undertook projects more clearly national in scope. Congress authorized its first parkway project in 1913, the four-mile Rock Creek and Potomac Parkway, to connect Potomac Park with Rock Creek Park and the Zoological Park. In 1928, Congress authorized the Mount Vernon Memorial Highway to link the District of Columbia with Mount Vernon in commemoration of the bicentennial of Washington's birth. This project fulfilled at long last an idea started in 1886 among a group of Alexandria citizens. In 1930 this highway was renamed the George Washington Memorial Parkway, and enlarged in concept to extend from Mount Vernon all the way to Great Falls in Virginia, and from Fort Washington to Great Falls in Maryland (Alexandria and the District of Columbia excepted). One leg of this parkway network — the one that links Mount Vernon to the District — has been completed for its entire length and portions of two of the other three legs constructed. The George Washington Memorial Parkway was added to the National Park System in the Reorganization of 1933, the first Recreation Area to be incorporated into the System. During World War II Congress extended the National Capital parkway network by authorizing the Suitland Parkway to provide an access road to Andrews Air Force Base, and the Baltimore-Washington Parkway, whose initial unit provided access to Fort George G. Meade. The first was added to the National Park System in 1949 and the second in 1950. With these projects National Park Service responsibility for parkways in the vicinity of the National Capital reached its present limits. The Colonial Parkway in Virginia was the first authorized by Congress beyond the District of Columbia vicinity. It provided a landscaped 23-mile roadway link between Jamestown Island, Colonial Williamsburg, and Yorktown Battlefield as part of Colonial National Monument, authorized in 1930. The National Park Service now considers Colonial Parkway an integral part of Colonial National Historical Park rather than a separate area. A new era for National Parkways began with authorization of the Blue Ridge and Natchez Trace Parkways during the 1930's. These were not fairly short county or metropolitan parkways serving a variety of local and national traffic but protected recreational roadways traversing hundreds of miles of scenic and historic rural landscape. These different National Parkways started out as public works projects during the New Deal and were transformed into units of the National Park System. The Skyline Drive in Shenandoah National Park served as a prototype for the Blue Ridge Parkway. President Herbert Hoover conceived the idea of the Skyline Drive during vacations at his camp on the Rapidan. It was planned in 1931 and begun as a relief project in 1932. Following President Roosevelt's election Congress quickly enacted the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 to stimulate the economy. Among other provisions it authorized the Public Works Administrator, Secretary of the Interior Harold L. Ickes, to prepare a comprehensive program of public works including the construction, repair, and improvement of public highways and parkways. Senator Harry F. Byrd of Virginia, aided by others, seized the opportunity to propose the construction of a scenic roadway linking Shenandoah and Great Smoky Mountains National Parks as a public works project. President Roosevelt and Secretary Ickes embraced this proposal provided the states donated the rights-of-way. They agreed to do so and on December 19, 1933, the National Park Service received an initial allotment of four million dollars to start the Blue Ridge Parkway. It was jointly planned by the National Park Service and the Bureau of Public Roads. Congress formally added the Blue Ridge Parkway to the National Park System in 1936. The Blue Ridge Parkway is considered by many to be a Service triumph in parkway design, providing the motorist with a serene environment conducive to leisurely travel and enjoyment while affording him many insights into the beauty, history, and culture of the Southern Highlands. The 469-mile parkway, sometimes called a grand balcony, alternates sweeping views of mountain and valley with intimate glimpses of the fauna and flora of the Blue Ridge and close-up views of typical mountain structures, like Mabry's Mill, built of logs by pioneers and still operating. Begun in 1933 and well on its way toward completion in 1964, the Blue Ridge Parkway is the best known and most heavily used Recreation Area established by the Service during this period. The Natchez Trace Parkway is the second major National Parkway, a projected 450-mile roadway through a protected zone of forest, meadow, and field which generally follows the route of the historic Natchez Trace from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez, Mississippi. The Old Natchez Trace was once an Indian path, then a wilderness road, and finally from 1800 to 1830 a highway binding the old Southwest to the Union. In 1934 Congress authorized a survey of the Old Indian Trail known as the Natchez Trace for the purpose of constructing a national road on this route to be known as the Natchez Trace Parkway. The survey was completed the next year and in 1938 construction was authorized. By 1964 about half the parkway had been completed linking many historic and natural features including Mount Locust, the earliest inn on the Trace, Emerald Mound, one of the largest Indian ceremonial structures in the United States, Chickasaw Village and Bynum Mounds in Mississippi, and Colbert's Ferry and Metal Ford in Tennessee. Projects for additional parkways proliferated during the 1930's and many were revived after World War II. Among proposals seriously advanced, some of which were carefully studied were:

In 1964 the Recreation Advisory Council, established by Executive Order 11017, recommended that a national program of scenic roads and parkways be developed. Following President Johnson's Message to Congress on Natural Beauty in February 1965, such a program was prepared by the Department of Commerce entitled A proposed program for roads and parkways. It contemplated a $4 billion dollar program between 1966 and 1976. However, the Viet Nam war intervened and no new National Parkways have been authorized in recent years. With deepening national concern for the quality of our environment, in which proliferating automobiles appear to pose more problems than solutions, it seems likely the parkway branch of the Family Tree will remain much as it is for sometime to come. It is revealing to recall that the Wilderness Society was organized in 1935 partly to protest such crest-of-the-ridge roadways as the Skyline Drive and the Blue Ridge Park way, which its members viewed as intolerable intrusions into unspoiled wilderness. Only a small voice in 1935, the Wilderness Society grew in a single generation to become the single most influential citizen voice among many others behind the Wilderness Act of 1964 which, among other provisions, is intended to keep wilderness roadless. Recreational Demonstration Areas. Like the Blue Ridge Parkway, two other Recreation Areas in today's National Park System trace their origin back to the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 — Catoctin Mountain Park, Maryland, and Prince William Forest Park, Virginia. Among many other features, the National Industrial Recovery Act authorized federal purchases of land considered submarginal for farming but valuable for recreation purposes. The land purchases were made initially by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, but later transferred to the Resettlement Administration so the farmers could be resettled, and then, in 1936, turned over to the National Park Service as Recreational Demonstration Projects. By 1936, 46 projects containing 397,000 acres had been set up in 24 different states, mostly near metropolitan centers, to provide outdoor recreation for people from crowded cities. It was intended from the beginning that most of these projects would be turned over to states and cities for operation and in 1942 Congress provided the necessary authority. By 1946 most of the conveyances had been completed. The National Park Service retained Catoctin Mountain Park, site of Camp David, but 4,500 of its acres were transferred to Maryland. Prince William Forest Park (formerly Chopawamsic) was retained as a unit administrated by National Capital Parks. Some recreational demonstration lands were also added to Acadia, Shenandoah, White Sands, and Hopewell Village. Now largely forgotten, recreational demonstration projects left several permanent marks on the National Park System and illustrated again the ability of the Service to help meet changing social and economic conditions in the nation. Reservoir-related Recreation Areas. Five National Recreation Areas were added to the System between 1933 and 1964. This new type of federal park area grew out of large scale reclamation projects like Hoover Dam and multi purpose river basin development programs like the Tennessee Valley Authority which began in the 1930's and spread to river valleys in all parts of the country after World War II. Lake Mead was the first National Recreation Area. The Boulder Canyon Project Act, passed in 1928, authorized the Bureau of Reclamation to construct Hoover Dam on the Colorado River. Work began in 1931 and the dam, highest in the Western Hemisphere, was completed in 1935. The next year, under provisions of an agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation, the National Park Service assumed responsibility for all recreational activities at Lake Mead. These were to become extensive, for Lake Mead is 115 miles long with 550 miles of shoreline, several ancient Indian sites, much natural history, and numerous facilities for camping, boating, swimming, and fishing. By 1952 Davis Dam had been built downstream, impounding 67-mile Lake Mohave whose upper waters lapped the foot of Hoover Dam. The National Park Service accepted responsibility for recreational activities around Lake Mohave as part of the Lake Mend National Recreation Area. The great size and importance of this combined recreational complex is easily under-estimated by persons who have not seen it. This one National Recreation Area contains 1,913,816 acres, making it roughly the size of Mount McKinley National Park or Death Valley National Monument. On October 8, 1964, Lake Mead was formally established as a National Recreation Area by Act of Congress. Coulee Dam National Recreation Area was established in 1946, under an agreement with the Bureau of Reclamation patterned after Lake Mead. Construction of Grand Coulee Dam began in 1933 and the dam went into operation in 1941. It impounds a huge body of water named Franklin D. Roosevelt Lake, 151 miles long with 660 miles of shoreline. The National Park Service has developed recreation facilities for camping, boating, swimming, and fishing at 35 different locations around the Lake. Coulee Dam is also well known for its visual and educational interest — the immense dam, long views across blue water and rolling hills, unusual geological features, and a variety of plants and animals, all in an historic context of Indians, trappers, soldiers, and pioneers. Although Millerton Lake, California, Lake Texoma, Oklahoma-Texas, and the north unit of Flaming Gorge, Utah-Wyoming were administered by the Service for a time, the first was subsequently turned over to the State of California, the second to the Army Corps of Engineers, and the last to the Forest Service. Three more National Recreation Areas established during the 1950's are still in the National Park System today. Shadow Mountain, adjoining the west entrance to Rocky Mountain National Park, embraces the recreational features of Lake Granby and Shadow Mountain Lake, two units of the Colorado-Big Thompson Project. Glen Canyon was established in 1958 to provide for recreational activities on Lake Powell formed behind Glen Canyon Dam on the Colorado River, one of the highest dams in the world. Both these areas are administered by the Service pursuant to agreements with the Bureau of Reclamation. The Whiskeytown-Shasta-Trinity National Recreation Area, California, was established by Act of Congress in 1962. The National Park Service, however, administers the recreational facilities only at Whiskeytown Reservoir, while the Forest Service takes care of similar, more extensive facilities at Shasta and Trinity. By 1964, application of the National Recreation Area concept to major impoundments behind Federal dams, whether constructed by the Bureau of Reclamation or the Corps of Engineers, appeared to be well accepted by Congress. Eight more reservations of this type were authorized as additions to the National Park System between 1964 and 1972. National Seashores. The National Park Service made its first seashore recreation survey in the mid-1930's. It resulted in a recommendation that 12 major stretches of unspoiled Atlantic and Gulf Coast shoreline, with 437 miles of beach, be preserved as national areas. World War II intervened and by 1954 only one of the 12 proposed areas had been authorized and acquired — Cape Hatteras National Seashore, North Carolina. All the others save one — Cape Cod — had long since gone into private and commercial development. Seashore studies were resumed by the Service in the mid-1950's through the generous support of private donors. These new shoreline surveys resulted in several major reports including Our Vanishing Shoreline (1955); A Report on the Seashore Recreation Survey of the Atlantic and Gulf Coasts (1955); Our Fourth Shore, Great Lakes Shoreline Recreation Area Survey (1959); and Pacific Coast Recreation Area Survey (1959). Detailed studies of individual projects were also prepared as a part of the Service's continuing efforts for shoreline conservation. By 1972 fruits of this program included eight National Seashores and four National Lakeshores of which the first four were authorized before 1964. Cape Hatteras, North Carolina, was authorized as the first National Seashore by Congress in 1937. Land acquisition lagged, however, until after World War II. Then two generous benefactors, the Old Dominion Foundation, established by Mr. Paul Mellon, and the Avalon Foundation, created by Mrs. Ailsa Mellon Bruce, made substantial and equal grants to the National Park Service which, matched by the State of North Carolina, made acquisition of Cape Hatteras possible. Cape Hatteras protects almost 100 miles of barrier islands and beach along the North Carolina coast. The National Seashore combines preservation of unspoiled natural and historical areas with provision, at suitable locations, for beachcombing, surf bathing, swimming at protected beaches, surf and sport fishing, bird-watching and nature study, and visits to such historic structures as Cape Hatteras Lighthouse and the remains of shipwrecks still buried in the sand. Cape Hatteras was a pioneering example of a new type of area in the National Park System. Cape Cod National Seashore, authorized in 1961, followed Cape Hatteras into the System. But it was the first of the great series of eleven post-World War II seashores and lakeshores approved by Congress in the last dozen years. It was the first large recreational or natural area for which Congress at the very outset authorized use of appropriated funds for land acquisition. An unusual provision of the Cape Cod act also authorized the Secretary of the Interior to suspend exercising the power of eminent domain to acquire private improved property within seashore boundaries as long as the town involved adopted and retained zoning regulations satisfactory to him. This provision resolved serious problems of conflict between long-settled private owners, the historic towns, and the Federal Government and helped stabilize the landscape without the forced resettlement of numerous families. It also created an important precedent for parallel provisions in legislation authorizing other national seashores and lakeshores where Federal, State, local, and private property interests required similar reconciliation. This National Seashore protects the great outer arm of Cape Cod, known to mariners from the days of the explorers and Pilgrims. Thoreau named it the Great Beach and said "A man may stand there and put all America behind him." For three centuries, Cape Cod, with its magnificent shoreline, was spared the great industrial buildup of our eastern coast. Combined with a seafaring way of life and a proud heritage, this isolation produced a memorable scene: great sand dunes, salt and fresh water marshes, unique villages, weathered gray cottages, fishing wharves, windmills, lighthouses, and an abundance of shore birds, migratory waterfowl, and other natural and historic features. Real estate subdivisions and commercial development threatened Cape Cod in the late 1950's, and Congress authorized permanent protection of some 27,000 acres of seashore and dune lands embraced in a narrow strip almost 40 miles long, from Provincetown to Chatham. The National Seashore concept reached the Pacific Coast in 1962 with authorization of Point Reyes, California, embracing more than forty miles of shoreline including historic Drakes Bay, Tomales Point, and Point Reyes itself. Acquisition of lands is still in progress. Protection of this immensely important and relatively unspoiled shoreline resource, only an hour's drive northward from Golden Gate, is the objective and obligation of the National Park Service under the 1962 act. The National Seashore concept reached the Gulf Coast in 1962 also with authorization of Padre Island, Texas. This great shore island stretches for 113 miles along the Texas coast from Corpus Christi on the north almost to Mexico on the south, and varies in width from a few hundred yards to about three miles. There is some private development at each end of the island. The National Seashore boundaries encompass the undeveloped central part of the island, over eighty miles long. Padre Island is a textbook example of a barrier island built by wave action and crowned by wind-formed dunes. CONCLUSION The above account of Recreation Areas added to the National Park System provides only a partial glimpse of the exceptional momentum developed by the national movement for parks and recreation between 1933 and 1964. The National Park Service, especially through the leadership of Conrad L. Wirth, as CCC administrator, planner and Director, played an influential role in that movement throughout this period. The need for more outdoor recreation facilities approached crisis proportions before the end of the 1950's, the result of growing population, increasing leisure time, rising incomes, and the automobile age. In 1958 Congress created an Outdoor Recreation Resources Review Commission to make a new comprehensive study of recreation facilities in the United States. The Commission presented its report, Outdoor Recreation for America, to President John F. Kennedy in 1962. Based on that report, Secretary Udall established the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation in the Department of the Interior in April 1962 and transferred longstanding National Park Service responsibilities for the formulation of a nationwide outdoor recreation plan and important aspects of cooperative relationships with States to the new bureau. In May 1963, Congress passed organic legislation confirming the responsibilities of the Bureau of Outdoor Recreation. With this action a new chapter in federal participation in outdoor recreation began. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||