CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

Cedar Breaks National Monument

|

This article contains an extract from the Courier: The National Park Service Newsletter, Vol 4, No. 1, January 1981. Alaska: A New Frontier for NPSby Candace K. Garry Public Information Specialist Office of Public Affairs, WASO Author's Note: There is an element of frustration, trying to condense all of Alaska into 2 weeks. It can't be done. Also, there is the challenge to understand, in a short time, how NPS employees in Alaska feel about the Service's mission and our future there. I spent hours and hours talking to dozens of people, some new to Alaska, some who had been there for as long as 32 years. Yet, I only scratched the surface, for there is much to know and even more to understand. Many of Alaska's mysteries will unfold in the years to come, as the Park Service begins its task of managing new NPS areas created by recently passed Alaska lands legislation. The legislative mandate also will mean changes for the Park Service in Alaska. This article highlights what a few Park Service employees in the Alaska Area Office shared with me during my visit to Anchorage, just 3 months before Alaska lands legislation finally cleared the Congressional hurdles and was signed by the President. It also highlights what a few of them have shared with me since, and some of Director Dickenson's thoughts about the future of NPS in Alaska. COURIER will publish articles about individual Park Service employees and areas in Alaska, in future issues.

After years of complex negotiation and discussion, the National Park Service's role in Alaska was resolved by the passage of the Alaska Lands Bill, signed into law by President Carter on Dec. 2. The legislation supercedes the President's proclamations creating a series of national monuments in Alaska under the authority of the Antiquities Act of 1906. President Carter signed the bill 2 years and 1 day from the date he declared the monuments in Alaska. Under the new law, every Park Service area in Alaska except the two small national historical parks is affected directly. The three oldest large Alaska parks—Glacier Bay and Katmai National Monuments and Mount McKinley National Park—have new boundaries and new status as national parks, with Mount McKinley assuming the traditional native name for its dominant peak—Denali.

Five of the monuments proclaimed in 1978 have also been redesignated as national parks, two retaining the title of national monuments. Ten national preserves were created, three encompassing proclaimed monuments, seven sharing names and boundaries with adjoining national parks or monuments. The essential difference between the preserves and the national parks is a provision for public hunting and trapping within the preserves. In addition, 13 wild rivers were designated for Park Service administration, all but one lying entirely within the boundaries of the newly created parks, monuments, and preserves. The law also establishes 32.4 million acres of wilderness within the Alaska components of the National Park System. Few in NPS are more elated about the passage of Alaska lands legislation than Alaska Regional Director John Cook. He had consistently entertained only positive thoughts about the outcome of an Alaska lands bill. He would speak only of when the bill would pass rather than if the bill would pass. Despite his unyielding optimism, he is "relieved, very relieved," that there is finally a bill. "Now we have a legislative mandate and the argument over whether or not the President should have or should not have used the Antiquities Act is moot," he says. Director Dickenson characterizes the Park Service role in Alaska as one of stewardship. "If you look at what stewardship really means, you will see that it means you preserve, conserve and protect for the use and enjoyment of someone else." Dickenson adds that he believes it is important not to "force progress on Alaska" at an accelerated pace. "The important thing," he says, "is to make sure that the abundance of resources there is not subjected in any way to abuse that would preempt choices for future generations." Dickenson commends the many dedicated Park Service employees who have tromped the mountains of Alaska, kayaked its winding rivers and flown over its breathtaking landscapes in search of the best possible boundaries for Park Service areas. "They have put an awful lot of time and energy into Alaska from a professional standpoint," he says.

AAO: A REGIONAL OFFICE Culminating the changes for the Park Service in Alaska, Secretary Andrus has designated the Alaska Area Office as a full administrative region of the National Park System, placing it on equal footing with the nine existing NPS regions. The Secretary's action of Dec. 2, immediately after the signing of the Alaska legislation, is formal recognition of the vast responsibilities the new law places on the NPS administrators in Anchorage.

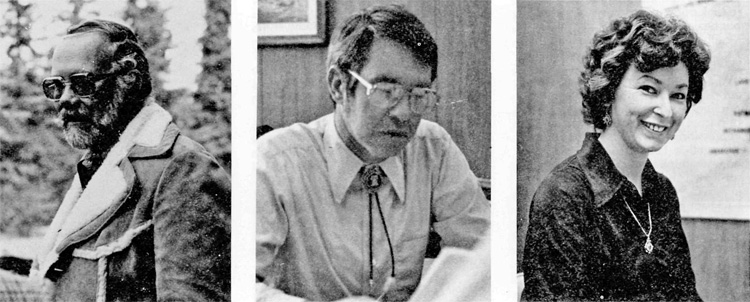

However, formal regional status for the Anchorage office won't mean major changes early on, according to NPS officials there. They say the Alaska Area Office has operated much like a regional office for quite some time. Alaska park areas, which traditionally reported to the Pacific Northwest Regional Office in Seattle, have coordinated most of their activities solely with the AAO since it was created. For sometime, AAO Director John Cook has reported directly to the Director of NPS. The transition to near-autonomy for the Anchorage office dates back to an arrangement made when Director Dickenson was Regional Director in Seattle. Although the Alaska Area Office does have a few remaining ties with Seattle in administration and payrolling, the office has worked directly with Washington in science and technology, ranger activities, legislation, and executive directions. As a result, Cook thinks there will be "few bumps in the road" as the Alaska Area Office becomes the Alaska Regional Office. "The real difference is perception, which means so much to people. There are staff people in Washington and everywhere who fail to include us in mailings to regional offices." Cook says that in the past, few recognized the AAO's need for material to meet deadlines because the office did not have the title of a regional office, even though the functions were similar. He thinks formal regional status will help change this. However, he says, the office will retain administrative ties with Seattle in payrolling and vouchering for some time. "All along, we've had an excellent relationship with the Pacific Northwest Regional Office." Before Alaska lands legislation passed there were 83 permanent, full-time NPS employees in Alaska, including 40 employees in the Anchorage office and less than 45 in field areas. Although that figure swells considerably when summer seasonals are hired, there haven't been large numbers of Park Service employees in Alaska. The bill provides for 24 positions in the new areas and six new positions in the Mining and Minerals office in Alaska. Cook says he has already classified and advertised the positions, which he expects to have filled by the end of this fiscal year. The new Alaska Regional Office will continue to adhere to an organizational plan devised and adopted while Anchorage was still an area office. Under this plan Cook, Deputy Director Doug Warnock, Public Information Officer Joan Gidlund, and Special Assistant to the Director Robert Belous comprise the top level of the organizational pyramid. Park superintendents also report directly to Cook, as do three associate directors, charged with a myriad of responsibilities within the region. Associate Director for Operations Bob Peterson is responsible for Ranger Activities & Visitor Services, Maintenance, and Natural Resources & Science Divisions. Associate Director for Professional Services Howard Wagner oversees Planning & Environmental Compliance, Cultural Resources & Compliance, Land and Minerals, and a Cooperative Park Studies Unit at the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. Personnel, Budget & Programming, Finance, and Contracting & Property Management are all divisions under the direction of Jim Behrens, associate director for administrative services. Behrens also has responsibility for a Native Liaison & Recruitment Program directed by Ellen Hayes, a Southeast Alaska Native and former Sitka National Historical Park superintendent.

DIFFERENCES IN ALASKA FOR NPS A unique feature of the Alaska lands legislation is the number and magnitude of preserves in Park Service areas in Alaska. "We're going to be dealing with such things as sport hunting in those preserves," says Deputy Regional Director Doug Warnock. "And subsistence, which is entirely foreign to our concept elsewhere in NPS, is going to be a major function." The Park Service must deal also with intrinsic differences in Alaska. Among them are the magnitude of the State itself, the often primitive conditions, and the forbidding climate in some areas. "You have to adopt a new kind of framework, a new kind of attitude, when you deal with Alaska," says Director Dickenson. "You cannot describe Alaska in terms of 'lower 48' adjectives. . . the times, the distances, heights, and conditions present there are just not duplicated in the lower 48." Deputy Regional Director Warnock thinks most people understand basically what the resources, scenery and wildlife in Alaska may be like. "Also, there may even be some realization about the difficulty of logistics in transportation and shipping because of weather conditions and that sort of thing," he says.

Logistics is precisely why Becky Kaiser, Administrative Assistant to Regional Director Cook, likes to have people visit Alaska. "It's important for them to see our physical layout, our working space, and to understand the vastness of the areas by seeing them first-hand," she says. Becky, who also arranges trips to NPS areas in Alaska for Interior officials and VIPs, says it can sometimes be difficult if people don't understand the geography of the unique nature of Alaska. "The easiest way to explain the vastness, the mobility problems, is to remind them that Alaska spans four time zones. . . most people don't stop to realize that!" She chuckles a bit when she tells about a recent caller who asked her to connect him with Mount McKinley (now Denali). "Mount McKinley is about 270 miles from Anchorage, and yet most people who have never been here think it's just on the outskirts of Anchorage." Planning could prove to be a different kind of challenge for the Park Service in this vast new land. "Planning will boom under this legislation," says Chief of Professional Services Howard Wagner, "because we have only 5 years to produce master plans for all the new areas." Wagner says the areas will work with the Denver Service Center for much of the planning. "This is truly different up here, and many of the problems we face will involve a hard look at our internal policies in personnel, logistics, and visitor wants and needs. All these things have to be carefully planned for," he adds. Regional Director Cook says he prefers a very pragmatic, conservative approach to planning for the areas in Alaska. "As we develop the planning, we need to zero in on each area, first as its own entity, and then as it fits into the Alaska system and to the National Park System." For example, access and visitor services will be more crucial at some areas than at others, according to Cook. "Development may never be right for some of these areas," he adds. "We have to evaluate the resources, the accessibility, and the types of use that each area can take. We must, in our planning, project visitation trends, and look at national economic trends, transportation trends. . . it all affects what we do." Cultural resources are another unique challenge in Alaska NPS areas. Regional Cultural Resources Director Bill Brown says he finds that he and others have learned that many Park Service values are "turned upside down" by the very nature of the unusual, different culture in parts of Alaska. "Our challenges are great because we have Natives living in the areas and their lifestyle is a significant part of the cultural resources," he says. He cautions that we must be sensitive to these delicate cultural landscapes.

ATTITUDES AND COMMUNICATIONS

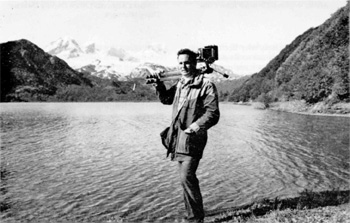

Attitudes toward the Park Service in Alaska range from respect and gratitude to old-fashioned, anti-government resentment. "There is no homogenous attitude here," says Bob Belous, a special assistant to John Cook. Belous, a well-known photographer, has traveled the far corners of Alaska, and knows many of the Natives in villages and remote areas across the State. He claims attitudes vary greatly, but that this variance does not appear in the news media. "The attitudes reflected in the media here used to be generally negative, but they are changing." He points out that in many areas the Park Service is well-respected and that it "has a positive rapport with people," but he adds that this is rarely reflected because "the press reflects Anchorage, Fairbanks, and Juneau." This, according to Belous, does not give a true picture of what is going on in the remote places where Park Service areas are. "The only part of the Park Service in Anchorage is the Regional Office. The parks themselves are far removed, and that's where the action is" adds Belous. However, the Park Service, he says, is seen by an increasing number of Alaskans as a "protector of landscapes and resources that have been recognized as vital to people in certain parts of the State." Regional Director Cook thinks once-negative attitudes are changing. "I look at the first time Doug Warnock and I flew into Eagle or when I went into Duffy's Tavern in McCarthy a year and-a-half ago, and I compare that with when we had our first task force meeting up here last summer. . . it's incredible, and rewarding, how the level of acceptance, understanding, and communications has improved," he says. Cook refuses to replace the "bullet-bitten" glass in what was his office window when he first became AAO director. "When the time comes, I'm going to take out that glass with five bullet holes in it, frame it, and it's going to be a part of a montage of keepsakes," he laughs. "I think we have begun to turn a corner and I would like to look upon us as not wheeler-dealers, but healer-dealers." Still, rumors run rampant about the Park Service in Alaska. "I've never seen anything like it in my life," says Cook. "Miscommunications and rumors are atrocious up here at times." The Anchorage office, for example, receives calls from frantic backpackers under the impression they cannot set foot in Wrangell-St. Elias. "These people honestly think the entire area is totally off-limits!" exclaims one NPS employee in Alaska. Not so, people not only backpack in the Wrangells and all other Park Service areas, but they can also camp, fish, hike, and even hunt and trap in the preserves.

Communications, then, provides special challenges for the Park Service in Alaska. "The big challenge for me in public affairs," says Assistant to the Regional Director for Public Affairs Joan Gidlund, "is explaining exactly what the D-2 legislation means to Alaska now that it's passed. There is a log of misinformation floating around out there, and it is our job to correct that and explain things to these people." Gidlund knows that the traditional news release is not enough in Alaska. Besides using conventional media and public involvement meetings to communicate both in Alaska and nationally, she works with other land management agencies in cooperative efforts. All Interior Department bureaus in Alaska participate in the Alaska Land Managers Task Force. Gidlund heads a subcommittee of the task force that is charged with refining and improving public information efforts about Alaska. The task force is planning a joint-agency radio series on the Alaska Radio Network to inform and educate citizens about land issues and regulations in the State. Communication vehicles in Alaska are not always the same ones used in the lower 48. Personal contact although difficult in an area so vast, is essential. "No media routine of getting out information about regulations is enough in Alaska," according to Bob Belous. "While media is important, the Park Service in Alaska has not relied on that alone. Public involvement meetings have helped Alaskans affected by NPS regulations to understand in depth what they mean, and the meetings have allowed the Alaskans to have input." Belous says public involvement comes in a special form in Alaska. "Often it means making a little extra effort, like having English translated into a Native language that is better understood in a particular locale." But more important, says Belous, communications must not be one way. "Our meetings have emphasized this."

STAFFING AND EMPLOYEE PREPARATION

Selecting the right employees for work and life in Alaska will be yet another challenge for the Park Service, according to Associate Regional Director Jim Behrens. "Our method of selection for employees is going to be very important, because not everybody and his family can come up here and live in the boondocks the way some people are going to have to live," he says. Associate Director for Operations Bob Peterson doesn't think Alaska is unique in this respect. "The same principle applies to people who might transfer to the Everglades or to Washington, D.C., or to Philadelphia or Boston," he says. "One of the things that has to be considered is whether or not the employee really wants to make the move." Peterson does acknowledge that it is important for employees to understand what they are getting into, especially for their families. "The field areas in Alaska, although surrounded by great beauty, may not be a desirable place to live for some people," he adds. Some think Alaska could be a "rude awakening" for those who are unfamiliar with the conditions there. Employees and their families must be well-prepared for life in some of the remote, isolated areas of the State. The Alaska Land Managers Task Force has developed special personnel management guidelines for Alaska that discuss recruiting, training and the kinds of information that people moving to Alaska need to have. Since there won't be many NPS employees in Alaska initially, Director Dickenson says the Service need not organize a large, formal orientation process for newcomers. He, like Regional Director Cook, prefers training and orientation that is more personal and "one on one" with a focus on specific locations where employees will serve. Both Dickenson and Cook stress the importance of training of employees being sent to new areas by individuals very familiar with the areas where the new employees will be sent. Furthermore, "care ought to be exercised in selecting people who are stable and have no psychological problems in the first place, and have very stable family relationships," says Dickenson. "It's important that they have shown through past experience that they can handle stressful situations," he adds, "because significant psychological and sociological differences exist in Alaska. The whole pattern of human activity there produces stress that may not be experienced by those of us who are used to the rhythm of life in the lower 48."

THE CHALLENGES, THE FUTURE Although we finally have an Alaska lands bill, much remains to be seen about the long term effects the Park Service will have on Alaska, and about the effects Alaska areas will have on the Park Service. One thing is for certain: NPS employees in Alaska are looking forward to the challenges and excitement that lie ahead. Most of them agree that how Alaskans and other observers worldwide will feel about the Park Service in Alaska depends on how well NPS manages areas there. They add that it will also depend on how the Service adjusts, how sensitive it is, and how careful it is.

"Visitation, interpretation and the activities routinely performed in other national parks are important. But we must be careful that these activities do not submerge some of the local activities and values that are very important to the people living in these areas," cautions Bob Belous. No one knows how long it will take to decide on development or "non-development" of the various Park Service areas in Alaska. These areas are very large, very isolated, and access to many of them is difficult. "The number of users of these areas today is extraordinarily small," says Director Dickenson, "compared to the resources available." Looking to the future, Dickenson predicts there will not be major public use of the new areas until more facilities are available. Regional Director Cook sums up the feelings of many about the Service's challenge in this vast new land. He says that in Alaska we have the "opportunity to be doing what Stephen Mather and Horace Albright did at the very start of the National Park Service." He says we must be very careful about the decisons we make today because we are "laying the foundation for the future." For many dedicated Park Service employees, he adds, "That's the challenge."

Alaska Units of the National Park System

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||