CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

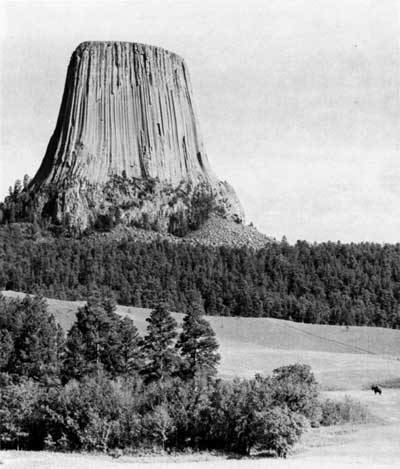

Devils Tower National Monument

NPS Centennial Monthly Feature

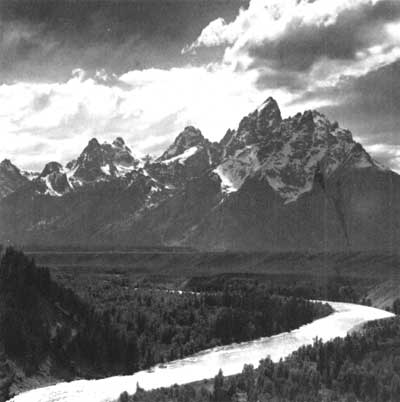

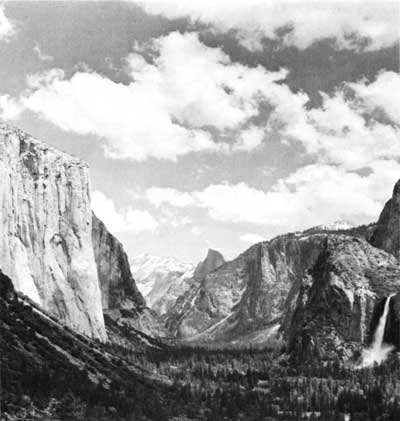

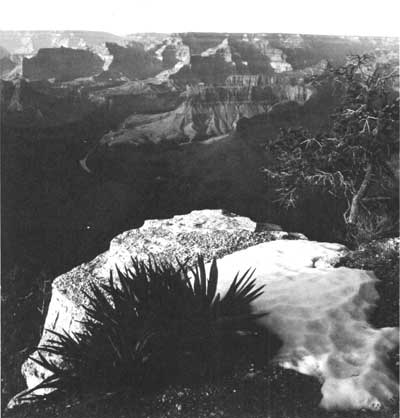

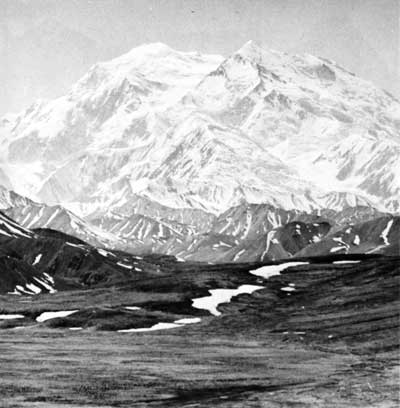

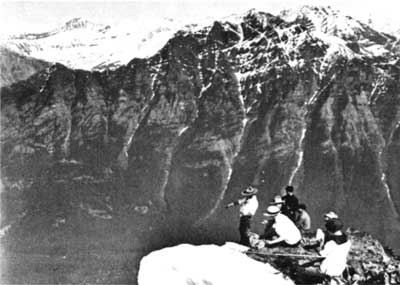

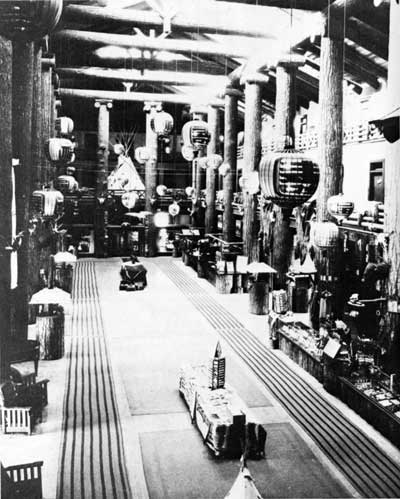

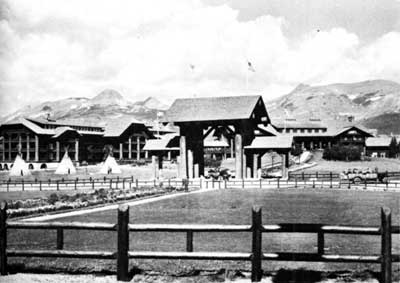

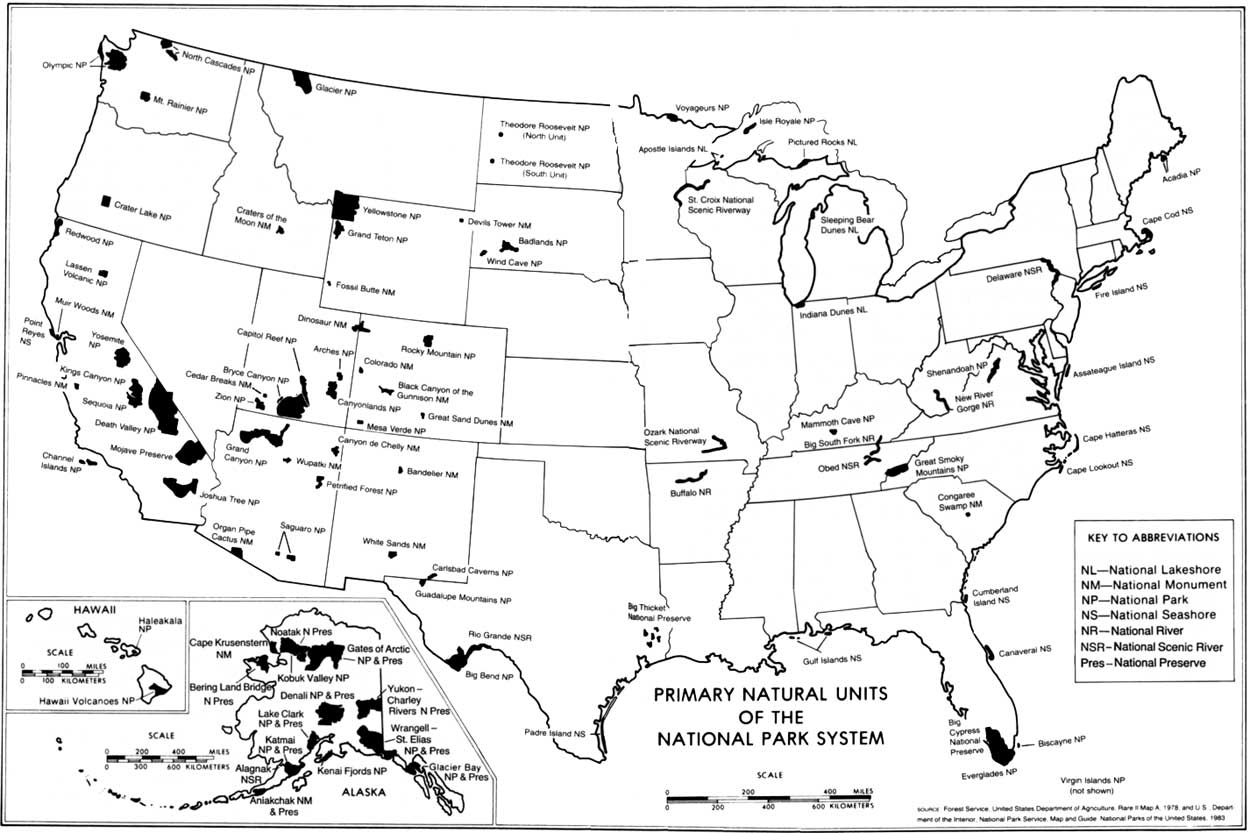

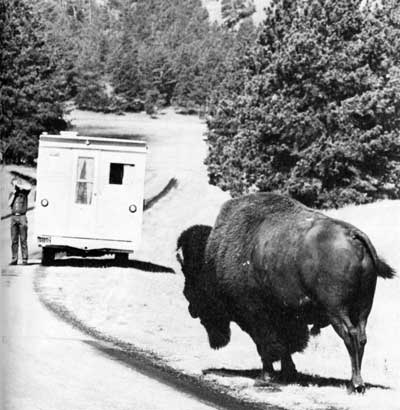

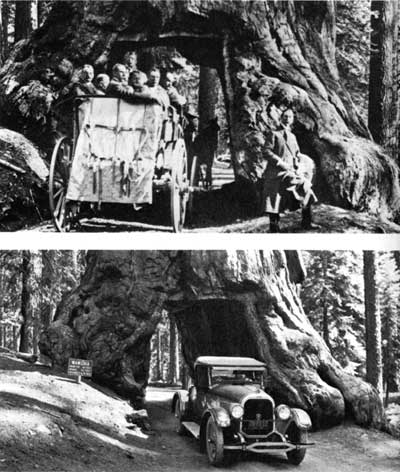

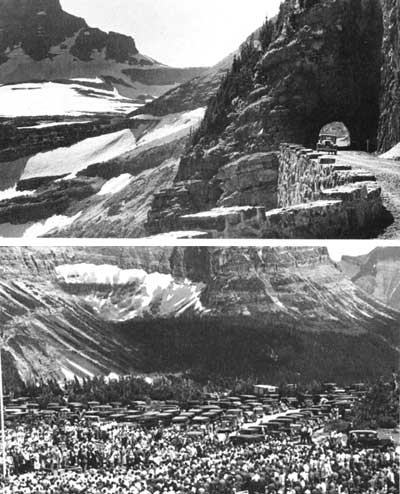

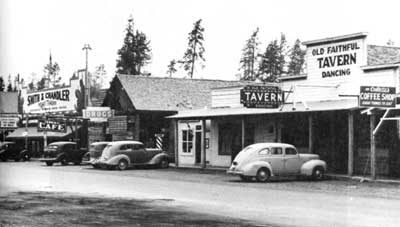

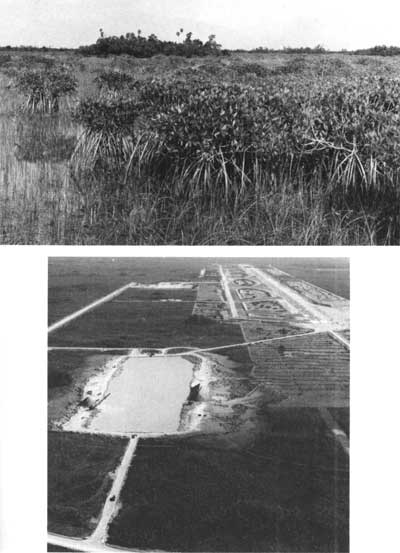

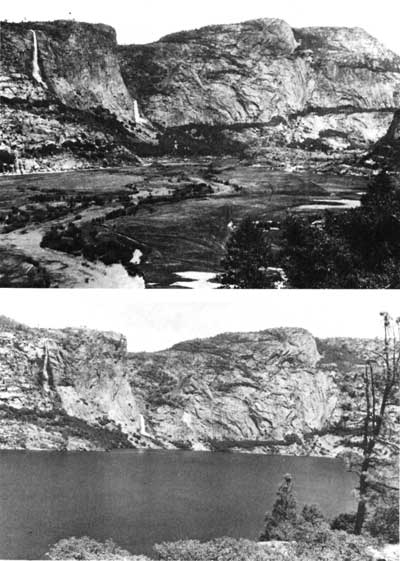

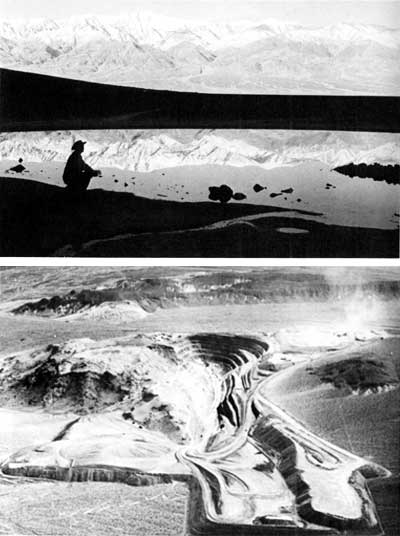

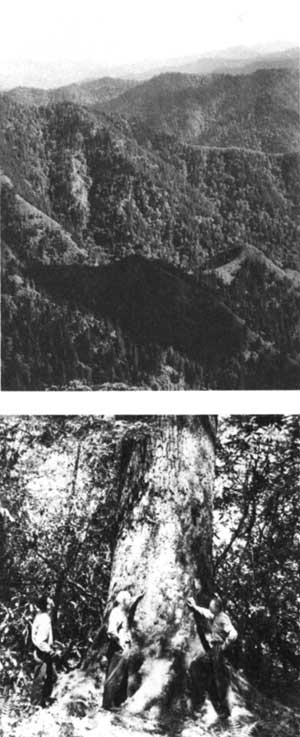

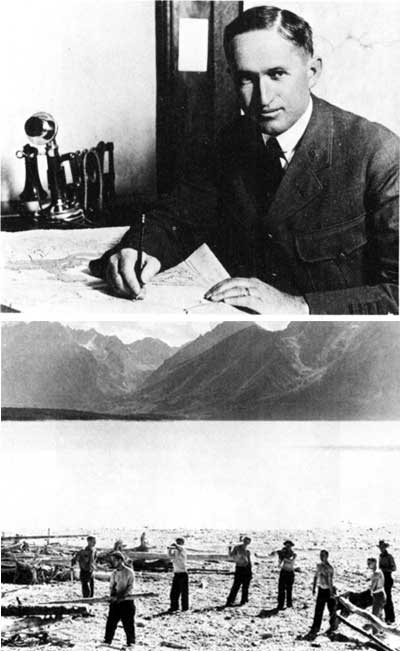

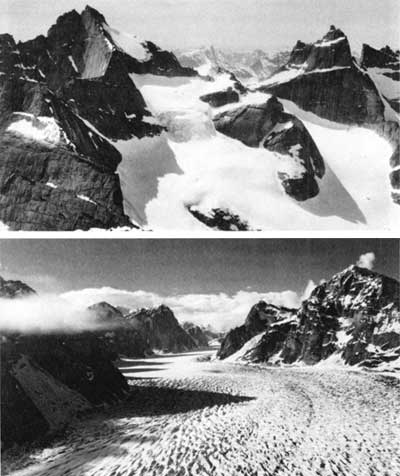

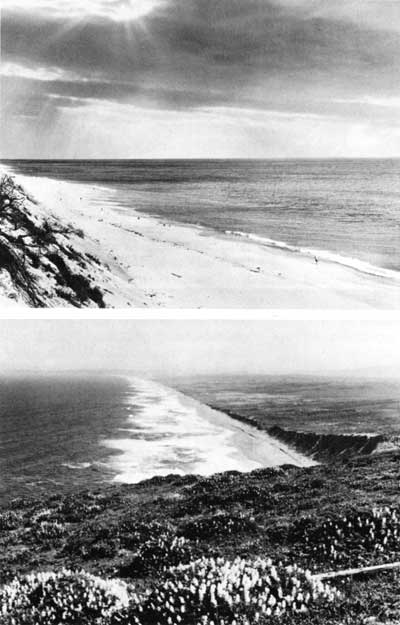

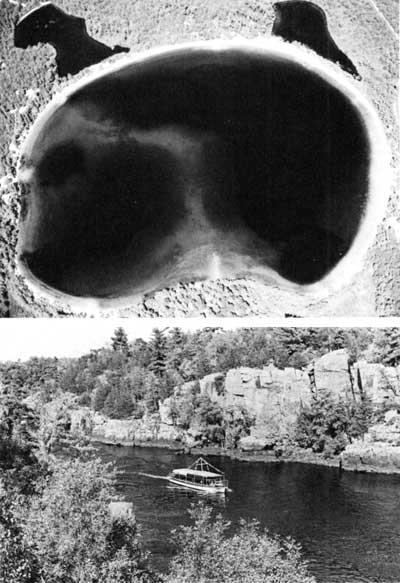

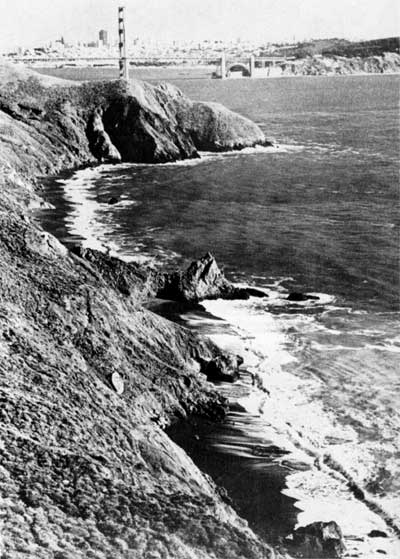

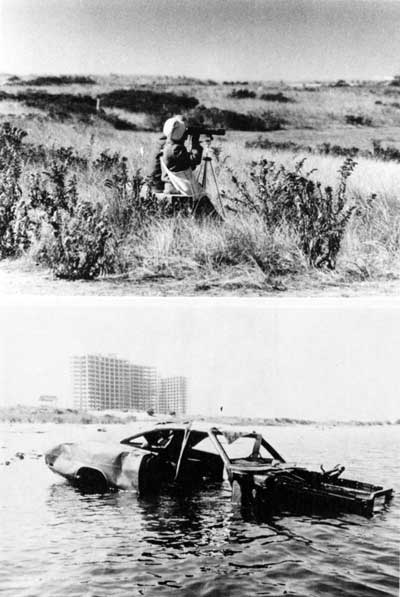

Contents List of Maps and Illustrations Frontispiece. Teton Mountains and Snake River. I. Monumentalism. Yosemite Valley; Niagara Falls; Harpers Ferry; Grand Canyon; Devils Tower; Mount McKinley; Glacier; Lower Falls of the Yellowstone; Mount Rainier; Olympic; Kansas prairie II. Railroads and the National Parks. Tourists in Yellowstone; Stephen T. Mather; Waitresses at Glacier; Gardiner, Montana, entrance to Yellowstone; Santa Fe Railway advertisement for Grand Canyon; Mount Stanton; Union Pacific Railroad advertisement for Bryce Canyon; Temple of Osiris, Bryce Canyon; lobby of Glacier Park Lodge; Glacier Park Lodge; Horseless carriage at Glacier Point, Yosemite III. Catering to Tourists. Camper and bison at Wind Cave; Theodore Roosevelt at Wawona Tunnel Tree, Yosemite; Automobile at Wawona Tunnel Tree; Touring cars in Glacier; Touring car at Old Faithful Inn; Going-to-the-Sun Highway; Dedication of Going-to-the-Sun Highway; West Yellowstone, Montana; Deer begging in Yellowstone; Auto log, Sequoia; Snowmobilists at Old Faithful; Easter sunrise service, Yosemite; Skating at Yosemite Winterclub; Removing debris from Blue Star Spring, Yellowstone; Bear Show, Yellowstone IV. Preserving the Environment. Everglades; Everglades Jetport; Hetch Hetchy Valley, Yosemite; Hetch Hetchy Valley, after being flooded; Crater Lake; Death Valley; Strip mine in Death Valley; Huggins Hell, Great Smokies; Tulip-Poplar tree, Great Smokies; Horace M. Albright; Removing debris at Jackson Lake; Logging near Redwood National Park; Shenandoah; Isle Royale V. National Park Expansion and Ecology. Arrigetch Peaks, Alaska; Ruth Glacier, Alaska; Cape Cod; Point Reyes, California; Great Pond, Cape Cod; St. Croix River; Marin Headlands, San Francisco; Bird watching, Gateway National Recreation Area; Abandoned high rise and car, Breezy Point; Gettysburg, Pennsylvania; Prescribed burn, Sequoia National Park; James Watt; Watt political cartoon Map 1. Primary Natural Units of the National Park System.

In Memory of My Mother and Father. No institution is more symbolic of the conservation movement in the United States than the national parks. Although other approaches to conservation, such as the national forests, each have their own following, only the national parks have had both the individuality and uniqueness to fix an indelible image on the American mind. The components of that image are the subject of this volume. What follows, then, is an interpretative history; people, events, and legislation are treated only as they pertain to the idea of national parks. For this reason I have not found it necessary to cover every park in detail; similarly, it would be impossible in the scope of one book to consider the multitude of recreation areas, military parks, historic sites, and urban preserves now often ranked with the national parks proper. Most of the themes relevant to the prime natural areas still have direct application throughout the national park system, particularly with respect to the problems of maintaining the character and integrity of the parks once they have been established. The indifference of Congress to the infringement of commercialization on Gettysburg National Military Park, for example, is traceable to the same pressures for development which have led to the resort atmosphere in portions of Yosemite, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and other parks. The reluctance of most historians and writers to dwell on the negative themes of national park history is understandable. National parks stand for the unselfish side of conservation. Take away the national park idea and the conservation movement loses its spirit of idealism and altruism. National parks justify the conviction that the United States has been as committed to do what is "right" for the environment as what is mandatory to ensure the productivity of the nation's natural resources. Without the national parks the history of conservation becomes predictable and therefore ordinary. Taking precautions to ward off the possibility of running out of natural resources was only common sense. The history of the national park idea is indeed filled with examples of statesmanship and philanthropy. Still, there has been a tendency among historians to put the national parks on a pedestal, to interpret the park idea as evidence of an unqualified revulsion against disruption of the environment. It would be comforting to believe that the national park idea originated in a deep and uncompromising love of the land for its own sake. Such a circumstance—much like the common assertion that Indians were the first "ecologists"—would reassure modern environmentalists they need only recapture the spirit of the past to acquire ecological wisdom and respect. But in fact, the national park idea evolved to fulfill cultural rather than environmental needs. The search for a distinct national identity, more than what have come to be called "the rights of rocks," was the initial impetus behind scenic preservation. Nor did the United States overrule economic considerations in the selection of the areas to be included in the national parks. Even today the reserves are not allowed to interfere with the material progress of the nation. It has been as hard to develop in the American public a concern for the environment in and of itself within the national parks as it has outside of them. For example, despite the public's growing sensitivity to environmental issues, the large majority of park visitors still shun the trails for the comfort and convenience of automobiles. Most of these enthusiasts, like their predecessors, continue to see the national parks as a parade of natural "wonders," as a string of phenomena to be photographed and deserted in haste. Thus while the nation professes an awareness of the interrelationships of all living things, outmoded perceptions remain a hindrance to the realization of sound ecological management throughout the national park system. Through personal encouragement and advice, many friends, relatives, and colleagues have contributed to the completion of this study. First mention is reserved for Marie Lundfelt Runte, who never doubted the value of this project nor wavered in her support. A special note of thanks is also due L. Moody Simms, Jr., and M. Paul Holsinger, both of the Department of History at Illinois State University, for their initial aid and counsel. Likewise, Bernard Mason, Albert V. House, Richard Dalfiume, and Robin Oggins, historians of the State University of New York at Binghamton, lent more time and attention to me as an undergraduate than either my discipline or performance then warranted. I am similarly grateful for the indulgence of my good friend and colleague Harold Kirker of the Department of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who cheered and strengthened me during my moments of frustration and indecision. An interpretative effort of this scope also owes recognition to the work of pioneers and practicing scholars in the fields of American intellectual history, the history of the West, and environmental history. Among them, Roderick Nash, Donald C. Swain, Douglas H. Strong, Richard A. Bartlett, W. Turrentine Jackson, Samuel P. Hays, Robert Shankland, John Ise, Aubrey Haines, and Hans Huth deserve special mention. I am directly indebted to Roderick Nash for encouraging this study from its inception. Richard Oglesby, also of the Department of History at the University of California, Santa Barbara, Joseph H. Engbeck, Jr., of the California Department of Parks and Recreation, and Richard A. Bartlett, professor of History at Florida State University, Tallahassee, similarly read and provided suggestions for the entire manuscript. Research was expedited by the generous cooperation of the staffs of several libraries, including the Bancroft Library, Library of Congress, National Archives, Pennsylvania Museum and Historical Commission, and University of California, Santa Barbara. Frederick R. Bell and Jonathan S. Arms of the National Park Service Photographic Division in Washington, D.C., were especially helpful in providing illustrations. In large part, my own research was made possible by Resources for the Future, Inc., of Washington, D.C., which granted me a full-year stipend during 1973-74 to complete my background work and begin writing. I am grateful to the editors of two journals for permission to repeat here ideas and information first published, in entirely different form, in "The National Park Idea: Origins and Paradox of the American Experience," Journal of Forest History 21 (April 1977): 64-75; "The Yosemite Valley Railroad: Highway of History, Pathway of Promise," National Parks and Conservation Magazine: The Environmental Journal 48 (December 1974): 4-9; and "Pragmatic Alliance: Western Railroads and the National Parks," National Parks and Conservation Magazine: The Environmental Journal 48 (April 1974): 14-21. To all of you again, my gratitude. In 1978, when I submitted the original manuscript of National Parks: The American Experience to the University of Nebraska Press, I realized the book would require periodic updating and revision. The national park system, after all, was still in the process of change and evolution. In 1978, for example, the battle for national parks in Alaska was just starting to intensify. Nearly three more years were to elapse before Congress and President Jimmy Carter approved the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. Similarly, there was serious discussion in 1978 of expanding the national park system to include a whole new assemblage of urban recreation areas, historic sites, and national trails. In the first edition, I discussed the issues of national park expansion only by inference. Now that I have had the time to reflect on the significance of these newer park categories, I consider it appropriate to devote an entire chapter to their rationale and establishment. The evolution of biological management in the national parks has marked another significant change in the direction of their history. More park administrators during the 1970s learned to respect the importance of natural processes, especially fire. Here again, the interval since my original research was completed has allowed time to consider new management ideologies in national park development. Finally, the administration of President Ronald Reagan has witnessed the rise and fall of undoubtedly the most controversial secretary of the interior in modern times, James Watt. I trust readers will therefore find it appropriate that I conclude this revision with a brief summary of Watt's impact on national park policy. These additions are themselves still selective. As I mentioned in the original preface, it would be impossible to include every citation, piece of legislation, contributing individual, or administrative detail in a history of the national park system. Some omissions are both necessary and desirable. The second edition, like the first, concentrates on the meaning of the national parks, their place in the origins and evolution of underlying perceptions of the American land. Meanwhile, I stand by my original interpretations. Among them none has been more debated than my observation that Congress allowed only those lands considered worthless from a natural resources standpoint to be set aside permanently as national parks. (See, for example, Richard W. Sellars, Alfred Runte, et al., "The National Parks: A Forum on the 'Worthless Lands' Thesis," Journal of Forest History 27 (July 1983): 130-45.) Perceptions of what Congress itself considered "worthless" varied with both the time and place, particularly after the turn of the century, when the "See America First" campaign provided the national parks with a unique commercial foundation of their own through tourism. This observation itself is not intended to refute their ecological and scenic significance. More to the point, it merely underscores the persuasiveness of economic arguments in determining precisely which scenery the nation felt it could afford to protect in perpetuity. As I originally explained, the term "worthless" grew out of the congressional debates. The word consistently referred only to the absence of natural resources of known commercial value, not to scenery, watersheds, or wildlife with obvious inspirational or biological—if not direct monetary—worth. Nor do I deny the value of national park lands purely as real estate. But of course land developers today would snatch at the opportunity to sell home lots and condominium sites along the shores of Yellowstone Lake and the rim of the Grand Canyon. Similarly, the national seashores, lakeshores, and riverways of the nation would be gold mines for such forms of development. The point is that Congress, at least with respect to the western parks, did not use the term "worthless" to describe real estate. Rather it was meant to assure prospective miners, loggers, farmers, and ranchers that national parks to be carved from the public domain were unsuitable for sustaining the traditional economic pursuits of the American frontier. Congress did, however, reassure the nation that any decision later found undesirable could just as easily be reversed. The uncertainty of preservation is itself a cornerstone of the worthless-lands thesis. As early as the Yosemite Park Act of 1864, preservationists argued that protection without permanence would be ultimately meaningless. If in fact Yosemite was sacred, then the park had to be protected not until Congress found some other use for it but rather as long as the United States existed, "inalienable for all time." The numerous compromises to the pledge of inalienability, either actual or implied, strike to the very heart of the worthless-lands argument. Like Indian reservations, the national parks have been subject to periodic readjustments. The issue, then, is not only how Congress said it would manage the parks but how Congress in fact allowed the parks to be treated. As I noted in the first edition, the "sin" of exploiting the parks has not been exploitation per se but defacement of the parks that cannot simultaneously be defended as being in the national interest. Consider again my original example of that enduring double standard, Niagara Falls. Real estate promotion led to the commercialization of Niagara Falls as early as the 1830s and 1840s. The defacement of the cataract by tourist sharks eroded its credibility as a symbol of national pride and achievement. Accordingly, as Americans entered the West, the lesson of Niagara Falls remained fresh in their minds. The natural wonders of the last frontier must not be lost to a similar fate. Niagara, however, also had great potential as a source of hydroelectric power. In contrast to the crass individualism associated with the tourist trade, the hydroelectric development of Niagara Falls promised to pay clear and unmistakable dividends to the nation's industrial base. Beginning in 1885, New York state pushed the hotels, souvenir stands, and other tourist traps back from the edge of the falls; the engineers, on the other hand, despite the tremendous impact of their own schemes on the very flow of the cataract itself, were allowed to pursue their diversions of the Niagara River well into the twentieth century. A similar situation evolved during the late 1970s along the southwestern corner of Yellowstone. No, I doubt that Congress would sell the national park itself to real estate promoters. In contrast, a geothermal project on the southwest boundary of Yellowstone has been under serious consideration since 1979 despite the risk of disrupting the underground reservoirs that feed the geyser basins within the park proper. Another example is Redwood National Park, whose expansion in 1978 came only after the logging companies had cut down the great majority of trees on the lands to be added to the existing preserve. The worthless-lands thesis does not deny the great commercial value of the redwood trees that remain; it merely underscores the observation that economic motivations have far outweighed long-range ecological considerations in deter mining how much land gets protected in the first place and, even more importantly, stays protected. Even as real estate alone, the national parks have not been immune to extensive exploitation by entrenched commercial interests. Granted, Congress has not allowed private condominiums to dot the shores of Yellowstone Lake; however, during the past century, concessionaires in the park have had great influence over the development of all of its primary attractions, including the lake, canyon, and geyser basins. The cabins, hotels, stores, motels, gas stations, and souvenir shops may be controlled by corporations rather than individuals but the proliferation of structures is nonetheless just as real and just as intrusive on the resource. The commercialization of Yellowstone and its counterparts invites historians, both now and in the future, to inquire again whether Americans truly value the protection of wilderness and wildlife, or whether most people simply prefer (or at least accept) that the parks be resorts ensconced in a more pristine setting. The evidence for this interpretation is abundant; it is simply not always popular to accept. To reemphasize, Americans prefer to think of their national park system as an unqualified example of their statesmanship and philanthropy. Critics of the worthless-lands thesis in particular have resorted to comforting but nonetheless undocumented speculation. Above all, they have argued that the worthless-lands speeches in Congress were nothing more than a "rhetorical ploy" to confuse potential opponents of the parks. Whoever the target of deception was, of course, the very act of deception may be seen as proof of its necessity. It would still follow that opposition to the parks on economic grounds was in fact both serious and legitimate. In either case, critics of the worthless-lands thesis have conveniently ignored how opponents of parks later would have reacted to the discovery of their having been duped by their associates. Afterward, it stands to reason, among the victims of deceit the opposition to further park proposals would have been even more serious, outspoken, and unyielding. Whatever else may be said in defense of speculation, it is still neither convincing nor definitive history. Granted, a long line of senators and congressional representatives friendly to the parks may have described those parks as "worthless" merely to throw their opponents off balance. Even with documentation to support that argument, however, the fact would remain that Congress, on nearly every occasion when important natural resources were located within major parks, seriously reconsidered the boundaries of those preserves. Most notably, in 1905 Congress reduced Yosemite National Park by 542 square miles to quiet objections raised by mining, logging, and grazing interests. In 1913, Congress further granted the Hetch Hetchy Valley within Yosemite National Park to the city of San Francisco for a municipal water supply reservoir. In other words, confronted with the evidence that it had mis judged the actual worth of those lands in 1890, Congress reneged on its misguided generosity. The worthless-lands speeches were not "rhetorical ploys." They were, in fact, serious assessments of national park lands based substantially on the findings of government resource scientists. I have not, as a result, found it necessary to change either the prologue or the original eight chapters of the book. If I were writing them today, I would add only a few more examples and quotations to support my initial discussions of monumentalism and the worthless-lands thesis. For instance, I would include additional evidence indicating that monumentalism was more than a metaphor, a simple effort to help the average American more easily visualize the natural wonders of the West. It is true that the landmarks of the region invited general comparisons to castles, cathedrals, and ruins. My point is that the imagery still had important cultural significance as well. In as many instances such comparisons were not general but rather site specific in nature. Observers of the West frequently depreciated the best of Europe's architectural attractions by describing them as inferior to the natural wonders of the region. On such occasions, when description turned into a strident defense of American landscapes over European art, cultural anxiety was clearly an important provocation. Lingering perceptions of the national parks as monuments of nature in large part explain why the American public is still distracted from perceiving current ecological problems. Indeed, were I attempting a complete revision of the book at this time, the one topic I would examine more closely would be wildlife conservation. The dilemma of protection is nonetheless obvious: protecting wildlife relies heavily on habitat preservation both outside and inside the parks. By the middle of the 1890s, government scientists, military park superintendents, and other observers had recognized the importance of expanding Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia national parks to include neighboring wildlife range and breeding grounds. That those parks, and others established later were only rarely enlarged to include other than rugged terrain explains why park scientists today still face an uncertain future in efforts to protect wildlife through the remainder of the century and beyond. Here again, I have not read recent struggles between environmentalists and developers back into park history. The concept of sanctuary is as old as the national park idea itself. Monumentalism inspired the national park idea among Americans and early preservationists at large. Defenders of the parks, however, especially those with an intimate knowledge of their plants, animals, and natural environments, spoke in terms of managing the national parks as sanctuaries from the very beginning. Frederick Law Olmsted, John Muir, and George Bird Grinnell, to mention only a few of those prophets, did not consistently advocate expansion of the parks simply to include only scenery within their borders. I begin my revision with an expanded version of the original epilogue, noting the importance of the environmental battles of the 1960s and 1970s in shaping the development of the national park system during those decades. Chapter 10, "Management in Transition," concentrates on fire ecology as an example of new trends in biological awareness. Chapter 11, "Ideals and Controversies of Expansion," traces the development of the so-called nontraditional parks, including seashores, lakeshores, wild and scenic riverways, and urban recreation areas. Chapter 12, "Decision in Alaska," further notes the influence of national park history on the great ecological preserves of the forty-ninth state. Even in Alaska, with its abundance of territory, Congress was careful to include only more marginal lands in national park areas. As a result, the book once more concludes on a note of uncertainty, emphasizing that the national parks throughout the continental United States in particular have finally arrived at their moment of truth. If the parks are to survive as ecosystems, not just as natural monuments, the time of decision is clearly at hand. If my fascination with the national parks initially inspired this book, then my concern about their future has certainly heightened my interest in their history. Although I am confident my interpretations will stand the test of time, I am obligated, as a professional historian, to remind the reader that I have lived through the period the revised chapters now address in the past tense. My perceptions of the national parks have been further shaped through several recent seasons as a ranger-naturalist and historian in Yosemite National Park. Again, it is only fair to acknowledge that any interpretation, however honestly conceived, can be subtly influenced by such personal experiences. My summers in Yosemite Valley educating the general public have been among the most challenging and rewarding of my entire career. I am especially grateful to all of my friends and colleagues in the Park Service who have shared with me their own observations and thoughts about the significance of national parks. I am also indebted to Frank Freidel, Frank Conlon, Robert Burke, Carlos Schwantes, Lewis Saum, and Arthur D. Martinson for their encouragement, interest, and support. Similarly, Richard A. Bartlett, Mott Greene, Lisa Mighetto, and Michael Frome offered me sound advice following close, critical readings of the entire revision. I also thank Thomas A. DuRant, Librarian, Branch of Graphics Research, National Park Service, Springfield, Virginia, for locating the additional illustrations. Finally, I thank my wife, Christine, for her patience and understanding while I clacked away on my typewriter instead of spending more of our first year of marriage with her. At the very least, I owe her a second honeymoon at Zion, Bryce, and the North Rim of the Grand Canyon. Yellowstone at 125: Now a century and a quarter old, Yellowstone maintains its popularity as the landscape closest to every ideal of what comprises a national park. Nor should the story of its exploration and founding as a scenic refuge ever grow tiresome. It is just that the story may never again seem as inspirational as when the country itself was young. Mounting pressures on the environment now betray the erosion of cultural attachments to both regional and national landscapes. Initially, in 1972, my research itself dampened the celebration of the Yellowstone Centennial. A hundred years earlier, I noted, the opponents of Yellowstone Park had insisted that it include nothing of proven commercial value.1 My cause for despair was my own preference for the utopian version of the evolution of national parks, in the words of the historian Wallace Stegner still "the best idea we ever had."2 The lost innocence of the national parks may indeed be the dominant theme of preservation in the twenty-first century. When this book originally went to press, the United States was preoccupied with the protection of national parks and wilderness. Now the future of Yellowstone, its fame aside, is but one of many concerns competing for the attention of the public and the media. Historians themselves remain divided between sentiment and objectivity. Like Wallace Stegner, many are tempted to celebrate national parks as the ideal expression of landscape democracy, despite evidence reaffirming that many parks have also been compromised or mismanaged.3 One inescapable cause of management problems is the extraordinary growth in traffic and visitation. The country that invented national parks held just thirty million people. As late as World War I, Yellowstone's annual visitation rarely exceeded 50,000. Moreover, the large majority came by train and stagecoach, part of a community of travelers bound to responsibility by limited access, poorer roads, and rustic accommodations. The nation about to carry Yellowstone into another millennium has ten times the population of 1872. Park visitation, both domestic and foreign, now exceeds three million every year. The park's sense of timelessness and benediction, of summer renewal and winter sleep, is lost amid a million cars and the drone of a hundred thousand snowmobiles. No different from any urban landscape, Yellowstone is constantly importuned, providing digression, but hardly sanctuary, from the complexities of the modern world.4 Meanwhile, economic forces dictate that extractive industries are still of greater value to the West than either wilderness or tourism. Thus, Noranda Minerals Inc., a Canadian conglomerate, opened the 1990s by pressuring federal officials to authorize a large gold and silver mine near Cooke City, Montana, barely two miles outside Yellowstone's northeastern boundary. For obvious reasons, any prior conviction that the region should be added to Yellowstone National Park had never been taken seriously, even though mining, first advanced more than a century ago, suggested only a modest strike. Over the years, existing mines were occasionally reworked and other mountainsides freshly scarred, little of which, it was argued, had spilled over into the park. Finally, technology overtook preservation with the invention of new extractive options. One technique, using cyanide as a leaching agent, coaxed as little as an ounce of gold from several tons of low-yield ore. Suddenly, what had once been only a marginal deposit was being hailed as the West's newest bonanza. Unfortunately, this time the mounds of tailings and a reservoir of toxic wastes might loom over a watershed feeding directly into Yellowstone.5 The so-called New World Mine brought home in the twilight of the twentieth century what had been true of the park ever since its establishment. Even as Congress in 1872 pledged its commitment to scenic preservation, it qualified repeatedly that Yellowstone's future indeed hinged on reassurances that only scenery was at stake. The mine was just the latest example of that historical precondition. In the end, the ambitions of American materialism still favored development over the ideals of conservation. To be sure, Congress had established many additional categories of national parks and their equivalent, including recreation areas, historic sites, wild rivers, and scenic trails. However, most tended to be corridors or islands on the American landscape, the majority significantly altered by prior development. Urban parks especially portended enormous costs for cleanup and maintenance, expenses generally not associated with areas traditionally reserved from the western public lands. Accordingly, if federal budgets persistently dwindled, as a mounting deficit seemed logically to predict, there was reason to fear that protection in the original natural units would also erode as one result. As if to sharpen that debate, in the summer and fall of 1988 Yellowstone was swept by a series of unprecedented wildfires. Virtually all of the park was affected by drifting smoke and ash, and approximately half of its forests burned, although intensities and tree loss widely varied. Dramatically, in late August and early September flames literally raced across the park, forcing firefighters into "last stands" around Yellowstone's endangered historic buildings. Other contingents battled to protect adjacent forests framing its primary scenic wonders. Weeks later, costs had surpassed a hundred million dollars to maintain an assault force still numbering several thousand people, including rangers, military personnel, and members of the National Guard.6 Finally, as the first snows of autumn snuffed out the still stubborn flames and hard-to-reach embers, the country began taking stock of its legendary landscape. The obvious reaction was despair, to pronounce Yellowstone hopelessly burned beyond historical recognition. And yet, the biological value of fire had many defenders, most insisting that any talk of tragedy had been grossly overstated. Granted, the fires had been serious and their intensity unforeseen. Too late, the Park Service had moved to suppress back-country burns worsened by lengthening weeks of heat and drought. Even so, Yellowstone in time would surely recover. In retrospect, fire seemed less an enemy of preservation than did a century of human abuse and manipulation.7 As another pivotal event in the history of the national parks, the Yellowstone fires refocused every debate regarding when to intervene in the management of natural environments. For a majority of Americans, Yellowstone's obvious appeal was still as the nation's distant, fabled "wonderland." Much relieved, everyone applauded that its geyser basins, canyon, and waterfalls had survived the flames intact. For others, however, wilderness was indeed the new criterion for maintaining the integrity of every natural area. In Yellowstone, the wolf had been exterminated and the grizzly bear long threatened with extinction. By implication, Yellowstone itself was hardly perfect. The term wilderness implied sanctuary, a landscape reserved for every native plant and animal as well as scenic wonders. Literature buttressed such convictions, including environmental history, which by now had also left the romanticism of the nineteenth century far behind. Notable books included Yellowstone: A Wilderness Besieged (1985), by the historian Richard A. Bartlett, and Playing God in Yellowstone: The Destruction of America's First National Park (1986), by a journalist, Alston Chase. Using different styles and approaches, both authors challenged the historical and contemporary priorities of the National Park Service. Development, they argued, often took precedence over the protection of key natural features.8 In another critical review, the historian Stephen J. Pyne noted the agency's tendency to ignore obvious distinctions between good and bad fires. Yellowstone, he concluded, had survived only because the park was truly big enough to absorb a million-acre holocaust, defined either as a natural occurrence or a management mistake.9 Regardless, within months of the fires, efforts to assess their long-term damage evinced a dwindling air of certainty. Through winter and into spring precipitation returned to normal. A minuscule percentage of the park, that portion where soils had been sterilized by the flames, showed no signs of imminent recovery. Elsewhere, in 1989 Yellowstone came alive in a sea of grass and wildflowers. It was, even skeptics admitted, one of the most glorious springs on record. Off through the blackened trees, long-forgotten vistas had reopened while, underfoot, millions of new seedlings were already taking root. Granted, many areas would take decades, even a century or more to recover fully. Then again, fires historically had reduced forest litter and undergrowth in cycles measured in years instead of centuries. What had appeared "natural" before the fires might be deceptive in its own right, self-generating, perhaps, but a landscape no less artificial than any of Yellowstone's most popular, developed areas.10 In that respect, the question of natural fire was part of the larger issue of Yellowstone's long-term survival. In the 1990s a new definition, Greater Yellowstone, addressed the park in further relation to the health of its neighboring lands. The thrust of its argument obvious, Greater Yellowstone included all potential wilderness surrounding the national park, another eight to ten million acres in addition to Yellowstone's original two. In short, Greater Yellowstone departed dramatically from cultural biases limiting preservation only to "worthless" lands. Inside the park, that criterion still prevailed; adjacent, however, lay many areas now designated for all forms of commercial development, including ranches, mining claims, logging operations, resorts, and summer homes.11 True, Greater Yellowstone referred primarily to lands still held in trust by the federal government. The vast majority, in national forests, further embraced several million acres already protected under the Wilderness Act of 1964. Even so, the national forests themselves were often pockmarked with commercial claims and private property. More critically, the U.S. Forest Service fundamentally disagreed that so much territory deserved set-asides as wilderness. On paper, the idea of buffering Yellowstone with everything outside the park might seem comforting and attainable. The hurdle, so easily discounted, was that it was no longer 1872. The reintroduction of the wolf in 1995 further aroused complaints of government indifference to the needs of local residents. Like the grizzly bear, wolves were prone to wander beyond the boundaries of the park itself. Among critics, the reintroduction cemented arguments that Greater Yellowstone presaged a government "taking," allegedly, a subtle but overt attempt to limit the rights of property holders without just compensation.12 Once again, the matter illustrated the futility of visualizing wilderness as something behind a fence. Wilderness was hardly real estate; it was a landscape immune to zoning or other forms of subdivision. Short of some sentiment for wilderness on private lands bordering any national park, wildlife as mobile as the wolf and grizzly bear was certain to face continuing persecution. Once again, any expansion of the national park system to round out the integrity of natural environments was restricted to topographic provinces where such additions would not impinge on civilization. Thus, the battle for Alaska behind them, preservationists renewed their interest in the deserts of California, Nevada, and Arizona. Yellowstone, as one result, ironically lost its preeminence as the largest national park in the continental United States. Under terms of the Desert Protection Act of 1994, Death Valley National Monument, expanded and redesignated as Death Valley National Park, now surpassed Yellowstone by more than a million acres.13 The successful outcome of the Desert Protection Act had indeed hinged on the matter of expansion without sacrifice. Greater Yellowstone conflicted with productive forests, growing communities, and several important watersheds. In contrast, the word desert seemed self-explanatory. The barren outcroppings of Joshua Tree National Monument, simultaneously expanded and renamed a national park, suggested, like Death Valley, the absence of traditional commercial values. Weeks earlier, Saguaro in southern Arizona made the same transition from a monument into a park. However, where mining, hunting, and grazing were still deemed significant, principally in California's East Mojave Desert, even a landscape so inextricably linked with visions of waste and hopelessness guaranteed no priorities for wilderness preservation. Designated only a national preserve, the East Mojave Desert served further notice of that enduring contradiction, the one bent on appeasement rather than closure of commercial claims to the nation's public lands.14 Although a century and a quarter old, the national park idea still awaited true consensus, a confirmation of cultural significance unaffected by expedience or remoteness. Indeed, earlier visionaries had considered parks but a necessary stage in the evolution of a more enduring ethic, one transcending political and social boundaries to see all land as sacred space.15 The proper evolution from Yellowstone into Greater Yellowstone was ultimately America the Beautiful. National parks should be more than reservations separating wilderness from the grasp of civilization. Rather, they should inspire Americans to care for every landscape, especially those enveloping their daily lives. Ideally, the future of the parks was projection, awareness rippling outward as well as people flowing in. A new philosophy, as it were, first demanded a new maturity. Behavior inappropriate to a national park was likely to be inappropriate anywhere. In that respect, the events preceding another major Yellowstone anniversary foretold an uncertain future for national parks and wilderness. For every achievement there was still ambivalence; for every success an element of national doubt. At least on the eve of the anniversary the news was mostly positive. In August 1996, President William Clinton announced an agreement with the Noranda company liberating Yellowstone from the proximity of the New World Mine. On payment of $65 million, and in exchange for other federal properties yet to be determined, Noranda pledged to relinquish all of its historical claims to the controversial New World site.16 Apparently, both Yellowstone and Greater Yellowstone had dodged a crippling blow to their respective identities as national park and wilderness. History alone raised the discomforting question: How long would any such agreement last? The euphoria of the moment conveniently masked that larger reality. For every victory came only the certainty of a different renewal of the threat. In that respect, Yellowstone at one hundred and twenty-five was really no more secure than Yellowstone at any anniversary in between. Earlier preservationists simply had the luxury of a smaller, less demanding population. No longer could Yellowstone, or any national park, survive all that civilization now portended. Contemporary celebrants could only hope the twenty-first century would bring no threat so serious it might undo every past success. If so, the original conviction of American nationalism would obviously have to hold. The glory of the United States lay in landscapes still pristine and undeveloped. Only then might wilderness survive the social and cultural changes spilling over into the next millennium. Only then might restraint possibly sustain the limitations of tradition, ensuring the timelessness of the national parks as the best idea America ever had. No institution is more symbolic of the conservation movement in the United States than the national parks. Although other approaches to conservation, such as the national forests, each have their own following, only the national parks have had both the individuality and uniqueness to fix an indelible image on the American mind. The components of that image are the subject of this volume. What follows, then, is an interpretative history; people, events, and legislation are treated only as they pertain to the idea of national parks. For this reason I have not found it necessary to cover every park in detail; similarly, it would be impossible in the scope of one book to consider the multitude of recreation areas, military parks, historic sites, and urban preserves now often ranked with the national parks proper. Most of the themes relevant to the prime natural areas still have direct application throughout the national park system, particularly with respect to the problems of maintaining the character and integrity of the parks once they have been established. The indifference of Congress to the infringement of commercialization on Gettysburg National Military Park, for example, is traceable to the same pressures for development which have led to the resort atmosphere in portions of Yosemite, Yellowstone, Grand Canyon, and other parks. The reluctance of most historians and writers to dwell on the negative themes of national park history is understandable. National parks stand for the unselfish side of conservation. Take away the national park idea and the conservation movement loses its spirit of idealism and altruism. National parks justify the conviction that the United States has been as committed to do what is "right" for the environment as what is mandatory to ensure the productivity of the nation's natural resources. Without the national parks the history of conservation becomes predictable and therefore ordinary. Taking precautions to ward off the possibility of running out of natural resources was only common sense. The history of the national park idea is indeed filled with examples of statesmanship and philanthropy. Still, there has been a tendency among historians to put the national parks on a pedestal, to interpret the park idea as evidence of an unqualified revulsion against disruption of the environment. It would be comforting to believe that the national park idea originated in a deep and uncompromising love of the land for its own sake. Such a circumstance—much like the common assertion that Indians were the first "ecologists"—would reassure modern environmentalists they need only recapture the spirit of the past to acquire ecological wisdom and respect. But in fact, the national park idea evolved to fulfill cultural rather than environmental needs. The search for a distinct national identity, more than what have come to be called "the rights of rocks," was the initial impetus behind scenic preservation. Nor did the United States overrule economic considerations in the selection of the areas to be included in the national parks. Even today the reserves are not allowed to interfere with the material progress of the nation. It has been as hard to develop in the American public a concern for the environment in and of itself within the national parks as it has outside of them. For example, despite the public's growing sensitivity to environmental issues, the large majority of park visitors still shun the trails for the comfort and convenience of automobiles. Most of these enthusiasts, like their predecessors, continue to see the national parks as a parade of natural "wonders," as a string of phenomena to be photographed and deserted in haste. Thus while the nation professes an awareness of the interrelationships of all living things, outmoded perceptions remain a hindrance to the realization of sound ecological management throughout the national park system. Previous editions of this book have gratefully acknowledged the many friends, relatives, and colleagues who contributed to its research and completion. All, accordingly, will understand if I now refrain from simply listing them yet again. Instead, I would like to give brief acknowledgment to the debt I owe an era, that time when history was about achievement more than about who had done what to whom. Perhaps, in everyone's insistence to be inclusive, historians have forgotten what true achievement means. I came from that side of the tracks where history now spends most of its time. No one need tell me how hard it was for immigrants, minorities, and working class families to get ahead. I know, because my parents were part of that struggle, wondering like everybody else how to get through another day. The point is that struggle also meant advancement, not only heartache but opportunity. History as I discovered it lifted the story of America to a higher plane, and me as well. I thank that age for its inspiration if not for its perfectibility, leaving perfection to those who really believe only remorse is now the answer.

The Heritage of Achievement and Indifference

More than a century ago, a small group of Americans pioneered a unique idea—the national park idea. It was the contention of this group that the natural "wonders" of the United States should not be handed out to a few profiteers, but rather held in trust for all people for all time. Gradually, as perceptions of the environment changed, national parks also became important for wilderness preservation, wildlife protection, and purposes closer to the concerns of ecologists. To be sure, the national park idea as we know it today did not emerge in finished form. More accurately, it evolved. Still, the values of the nineteenth century have remained influential, a fact which does much to explain why many national parks are still torn between the struggle for preservation and for use. Especially because most Americans still seek out spectacular scenery and natural phenomena, environmentalists caution that the public has little understanding of the restraints on visitation needed to protect the diversity of the parks as a whole.1 Who first conceived the idea of preservation is not known. Ancient civilizations of the Near East fostered landscape design and management long before the birth of Christ. By 700 B.C., for example, Assyrian noblemen sharpened their hunting, riding, and combat techniques in designated training reserves. These were copied by the great royal hunting enclosures of the Persian Empire, which flourished throughout Asia Minor between 550 and 350 B.C. It remained for the Greeks to democratize landscape esthetics; their larger towns and cities, including Athens, provided citizens with the agora, a plaza for public assembly, relaxation, and refreshment. Known for its fountains and tree-shaded walkways, the agora has been compared to the modern city park.2 Although urbanization throughout the Roman Empire led to similar experiments, Medieval Europe, like Asia Minor, reverted to the maintenance of open spaces exclusively for the ruling classes. Hunting once more became a primary use of these lands; in fact, the word "park" stems from this usage. Originally "parc" in Old French and Middle English, the term designated "an enclosed piece of ground stocked with beasts of the chase, held by prescription or by the king's grant."3 Trespassers were punished severely, especially poachers who often were put to death. With the possible exception of the Greeks and Romans, therefore, the park idea as now defined is modern in origin; only recently has it come to mean both protection and public access. Not until the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries did the appreciation of landscapes and democratic ideals rise to prominence throughout the Western world. In Europe, and later the United States, with the rapid spread of cities, factories, and their attendant social dislocations, people came to question whether the Industrial Revolution really represented progress. Locked into the drudgery and grime of manufacturing communities, more and more people followed poets and philosophers in embracing nature as the avenue of escape. The Romantic Movement, for example, in its praise for the strange and mysterious in nature, by definition preferred landscapes only suggestive of human occupation. Thus ruined castles or crumbling fortresses were valued because of what they implied; a concern for detail would have destroyed the enjoyment of trying to recall their former grandeur through one's own imagination. Others held that the ultimate state of nature might be the absence of civilization altogether. So argued deists and primitivists, at least, the former because man's works supposedly obscured God's truths, the latter in the conviction that man seemed happiest in direct proportion to the absence of his own creations.4 The egalitarian ideals of the American and French revolutions further joined urbanization and industrialization in undermining traditional beliefs. As a result, throughout Europe royalty finally lost the power to dictate solely when and how parklands were to be opened to the public at large. In 1852, for example, the city of Paris took over the popular Bois de Boulogne from the crown, with the agreement that its woods and promenades would be cared for and improved. London's royal parks, initially opened to the populace during the eighteenth century at the discretion of the monarch, similarly were enlarged and maintained for public benefit. Another important milestone on the road to landscape democracy in Great Britain was Victoria Park, carved from London's crowded East End. Authorized in 1842, it was the first reserve not only managed, but expressly purchased, for public instead of private use. Its counterpart in Liverpool, Birkenhead Park, likewise was to remain, in the words of one American admirer, Frederick Law Olmsted, "entirely, unreservedly, and for ever, the people's own. The poorest British peasant is as free to enjoy it in all its parts as the British queen. ... Is it not," he concluded, "a grand, good thing?"5 Olmsted, the son of a prosperous Connecticut family, returned home from his first visit to the Continent in 1850. He was then twenty-eight years old, and his career as America's foremost designer and proponent of urban parks lay some years in the future.6 Yet even as he praised Great Britain's commitment to provide urban refuges for the common man, the climate of opinion in the United States was already swinging decidedly in favor of the city park idea. As early as 1831 the Massachusetts legislature approved a "rural cemetery" on the outskirts of Boston, to be known as Mount Auburn. Shortly after its completion urban residents favored the site for picnicking, strolling, and solitude. Rural cemeteries caught on throughout the Northeast. By 1836 Brooklyn and Philadelphia, among other cities, were equally renowned for this popular, if unconventional, means of providing open space.7 If the nation could provide parklands for the dead, parklands for the living might also be realized. Two of the earliest proponents of the city park idea were Andrew Jackson Downing, a horticulturist, and the poet William Cullen Bryant. During the 1840s they called for the establishment of a large reserve within easy reach of New York City. Finally, in 1853 the New York legislature agreed to the plan by purchasing a rectangular site (the equivalent of approximately one square mile) on the outskirts of the metropolis. To be known as Central Park once the city had built up around it, the project launched Frederick Law Olmsted and his partner, Calvert Vaux, on their distinguished careers.8 Central Park set a precedent for preservation in the common interest more than a decade before realization of the national park idea. Still, while its debt to the city park is obvious, the national park evolved in response to environmental perceptions of a dramatically different kind. City parks were an eastern phenomenon, a refuge from the noise and pace of urban living. City dwellers wanted facilities for recreation, not scenic protection per se. Convenient access was of primary concern; a city park could be located anywhere, however distasteful the site. Portions of Central Park itself replaced run down farms, pig sties, and garbage dumps. Once a site had been obtained, the landscape architect readily made it pleasing to the eye by adding lakes, walkways, gardens, or playing fields as public demand warranted. Later, of course, the placement of roads, trails, and over night lodgings in the national parks called upon similar artistry and sensitivity to existing natural features. Yet beyond these concessions to access and convenience, from the outset Americans understood intuitively that the national parks were different. The striking dissimilarity was topographical. Unlike those who sought relief from the crowdedness and monotony of city streets, proponents of the national parks unveiled their idea against the backdrop of the American West. Grand, monumental scenery was the physical catalyst. The pioneers and explorers who emerged from the more subdued environments of the East found the Rocky Mountains, Cascades, and Sierra Nevada overpowering in every respect. Cliffs and waterfalls thousands of feet high, canyons a mile deep, and soaring mountains covered with great conifers were awesome to people born and bred within reach of the Atlantic seaboard. It is therefore understandable why many national parks, as distinct from urban parks, were established long before their potential for recreation could be realized. In the West the protection of scenery by itself was justification enough for modifying the park idea. As a visual experience, national parks went beyond the need for physical fitness or outdoor recreation. Indeed, the parks did not emerge merely as the end product of landscape appreciation for its own sake. Simply admiring the natural world was nothing unique to the people of the United States; the transcendentalists, including Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau, themselves followed the example of the likes of Shelley, Byron, Wordsworth, and Keats. The intellectual subtleties of transcendentalism, in any case, could hardly sustain the national park idea in a country as firmly committed to material progress as the United States. The decision not only to admire nature but to preserve it required stronger incentives. Specifically, the impulse to bridge the gap between appreciation and protection needed catalysts of unquestionable drama and visibility. In the fate of Niagara Falls Americans found a compelling reason to give preservation more than a passing thought. Although then recognized both at home and abroad as the nation's most magnificent natural spectacle, as early as 1830 the falls suffered the insults of so-called sharpers and hucksters of every kind. While some located adjacent to the cataract to tap its endless stream of power, still more came to fleece the growing number of tourists attracted by completion of the Erie Canal, and, close behind, the railroads. The mixed blessings of Niagara's popularity were soon apparent. Private developers quickly acquired the best overlooks, then forced travelers to pay handsomely for the privilege of using them. By 1860 gatehouses and fences rimmed the falls from every angle. No less offensive were hackmen, curio hawkers, and tour guides, who matched their dishonesty with annoying persistence.9 A continuous parade of European visitors and commentators embarrassed the nation by condemning the commercialization of Niagara.10 To be sure, although half the falls belonged to Canada, few mentioned this fact in defense of the United States; if Americans had no pride in their portion of the falls, they deserved no excuse. Among the earliest critics to write in this vein was Alexis de Tocqueville. In 1831, during the extended visit to the United States that led to his classic work, Democracy in America, he urged a friend to "hasten" to Niagara if he wished "to see this place in its grandeur. If you delay," he warned, "your Niagara will have been spoiled for you. Already the forest round about is being cleared... . I don't give the Americans ten years to establish a saw or flour mill at the base of the cataract." 11 By 1834 Tocqueville's worst fears had been confirmed, most memorably in the observations of a pair of English Congregational ministers, Andrew Reed and James Matheson. They noted that the American side now boasted the "shabby town" of Manchester. "Manchester and the falls of Niagara!" They made no effort to veil their disgust. "One has hardly the patience to record these things." Surely some "universal voice ought to interfere and prevent the money-seekers." The divines followed with nothing less than an appeal for international protection of the cataract. "Niagara does not belong to [individuals]; Niagara does not belong to Canada or America," they asserted. Rather "such spots should be deemed the property of civilized mankind." Their destruction, after all, compromised "the tastes, the morals, and the enjoyments of all men."12 If Reed and Matheson could have inspired their own countrymen to take action, perhaps England, and not the United States, would now be credited as the inventor of the national park idea. England certainly had a comparable opportunity, until Canada won its independence in 1867; the provinces boasted a variety of natural wonders, many on a par with those of the western United States. European countries simply lacked an equal provocation to originate the national park idea. If not for Great Britain, whose cultural identity was secure, for the United States each disparagement about its indifference to the fate of its natural wonders hit home. Although only verbal barbs, they unmistakably accused Americans of having no pride in themselves or in their past. "By George, you would think so indeed, if you had the chance of seeing the Falls of Niagara twice in ten years," said another English traveler, Sir Richard Henry Bonnycastle, repeating the popular charge in 1849. Granted, by now the fate of the falls was "a well-worn tale." Yet "so old a friend as the Falls of Niagara; for you must have read about those before you read Robinson Crusoe," surely deserved better than injury "by the Utilitarian mania." But "the Yankees [have] put an ugly shot tower on the brink of the Horseshoe," he lamented, "and they are about to consummate the barbarism by throwing a wire bridge ... over the river just below the American Fall.... What they will not do next in their freaks it is difficult to surmise," he concluded, then echoed Reed's and Matheson's disgust: "but it requires very little more to show that patriotism, taste, and self-esteem, are not the leading features in the character of the inhabitants of this part of the world."13 Later in United States history, when intellectuals had greater confidence in their nation's achievements, such derision would be more easily discounted. But now the United States agonized in the shadow of European standards. Unlike the Old World, the new nation lacked an established past, particularly as expressed in art, architecture, and literature. In the Romantic tradition nationalists looked to scenery as one form of compensation. Yet even the landscapes of the United States, knowledge of which was then confined to those in the eastern half of the continent, were nothing extraordinary. Confronted with the obvious, Americans had little choice but to admit that the landmarks of Europe, especially the Alps, were no less magnificent. Prior to 1850 America's best claim to scenic superiority was Niagara Falls, which, most Europeans themselves conceded, surpassed comparable examples in the Old World. But the onslaught of commercialism robbed the cataract of credibility as a cultural legacy. A monument, whether human or natural in origin, implies some semblance of public control over its fate. But the private ownership of the land adjoining Niagara Falls compromised that ideal, as noted by Tocqueville, Reed, Matheson, Bonnycastle, and their contemporaries. Redemption for the United States lay in westward expansion. As if reprieved, between 1846 and 1848 the nation acquired the most spectacular portions of the continent, including the Rocky Mountains and Pacific slope. Distance magnified their appeal, the more so as easterners endured urban drudgery, crowdedness, and monotony. This dichotomy between the settled East and frontier West further explains the timing of the national park idea. In effect the East was the audience to frontier events. For the West was a stage, a setting for the adventure stories, travel accounts, and dramatic paintings that characterized so much of the period. Indeed, Americans conquered the region precisely as popular literature, art, and professional journalism came of age. While the last frontier passed into history, the nation watched intently, if not in the field then through its dime novelists, newspaper correspondents, engravers, artists, and explorers. 14 As each of these groups glorified the West, Americans became aware that here the nation could redeem itself of the shame of Niagara Falls and prove its citizens worthy of great landmarks. Much as Europe retained custody of the artifacts of Western Civilization, so in the West the United States had one final opportunity to protect a truly convincing semblance of historical continuity through landscape. Niagara Falls, as the lesson of past indifference, warned Americans about the need to guard against similar encroachments on their new-found wonderland. For although the grandeur of the Far West inspired the national park idea, eastern men invented and shaped it. Thus as the nation moved west, the specter of Niagara remained fresh in the minds of those many people who had witnessed its disfigurement firsthand. These included Frederick Law Olmsted, whose familiarity with the cataract dated as far back as boyhood visits in 1828 and 1834.15 Between 1879 and 1885 he and a few close associates aroused the nation in support of efforts by the state of New York to restore the cataract and its environs to their natural condition.16 (Ontario followed suit with dedication of its provincial park in 1888.) Still, having opened the West, Americans finally could admit that the East as a whole was too commonplace to surpass the scenic landmarks of Europe. The likes of Yosemite Valley and Yellowstone, by way of contrast, needed no apologies. But only if they were faithfully preserved from abuse (the fate of Niagara still aroused the nation's conscience) would they be truly convincing proof of the New World's cultural promise. Here at last—in the blending of the eastern mind and the western experience—was the enduring spark for the American inspiration of national parks.

When national parks were first established, protection of the "environment" as now defined was the least of preservationists' aims. Rather America's incentive for the national park idea lay in the persistence of a painfully felt desire for time-honored traditions in the United States. For decades the nation had suffered the embarrassment of a dearth of recognized cultural achievements. Unlike established, European countries, which traced their origins far back into antiquity, the United States lacked a long artistic and literary heritage. The absence of reminders of the human past, including castles, ancient ruins, and cathedrals on the landscape, further alienated American intellectuals from a cultural identity.1 In response to constant barbs about these deficiencies from Old World critics and New World apologists, by the 1860s many thoughtful Americans had embraced the wonderlands of the West as replacements for man-made marks of achievement. The agelessness of monumental scenery instead of the past accomplishments of Western Civilization was to become the visible symbol of continuity and stability in the new nation. Of course the great majority of Americans took pride in the inventiveness and material progress of the nation; the search for a "traditional" culture was not among the public's chief concerns. Yet in order to claim that the general populace did not at least sympathize with the doubts of artists and intellectuals, first it would be necessary to discount the observance of their ideals in the popular as well as professional literature of the period. Indeed, much as Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and others fostered an appreciation of landscapes on an intellectual plane, so publicists of a more common bent aroused support for preservation while introducing their readers to the scenery of the Far West. Among the more articulate spokesmen of this genre was Samuel Bowles, editor and publisher of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican. Learned, socially respected, and well-to-do, Bowles typified the class of gentlemen adventurers, artists, and explorers who conceived and advanced the national park idea during the second half of the nineteenth century.2 With the conclusion of the Civil War in 1865, Bowles realized a long-held dream to see the West firsthand. The trip was made all the more enjoyable by the companionship of two prominent friends, Schuyler Colfax, Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives, and Albert D. Richardson, recently distinguished for his coverage of the war as a correspondent for the New York Tribune. The overnight success of Bowles and Richardson confirms how important the popular press was in laying the foundations of the national park idea. In contrast to the writings of Thoreau, which had a very limited following during his own lifetime, the Springfield Republican as early as 1860 enjoyed a strong circulation as far afield as the Mississippi Valley. The New York Tribune's circulation of 290,000 nationwide similarly reflected the growing popularity of general publications. Although much of this readership can be linked to interest in the Civil War, articles about the West remained in great demand throughout the conflict. And with the close of hostilities both Bowles and Richardson became best-selling authors. Bowles essays for the Republican alone sold 38,000 copies when collected and republished as Across the Continent and Our New West, released in 1865 and 1869 respectively.3 Richardson's Beyond the Mississippi, published in 1867, was equally popular. Like Bowles, Richardson therefore excited the East's fascination with the West. Curiosity about the great physical disparity between the landscapes of the two regions was especially great. "The two sides of the Continent," Bowles observed, "are sharp in contrasts of climate, of soil, of mountains, of resources, of production, of everything." Indeed, only in the "New West" had nature wearied "of repetitions" and created so "originally, freshly, uniquely, majestically." Throughout the Rocky Mountains and along the Pacific slope lay scenery "to pique the curiosity and challenge the admiration of the world." Surely none could doubt, he therefore concluded, that the West would contribute to the lasting fame and glory of the entire United States.4 Although Bowles addressed the issue of preservation only briefly, the evolution of his thinking demonstrates how cultural anxiety turned appreciation of the West into bona fide efforts to protect it. He arrived in Yosemite Valley in 1865 to find the gorge already set aside by Congress the previous year. The "wise cession," as he immediately praised the grant, should be looked to as "an admirable example for other objects of natural curiosity and popular interest all over the Union." New York State, for example, "should preserve for popular use both Niagara Falls and its neighborhood"; similarly, the state would be well advised to set apart "a generous section of her famous Adirondacks, and Maine one of her lakes and surrounding woods." By 1869, when Bowles revised the statement, he had grown even more outspoken. He now considered it nothing less than "a pity" that the nation had failed to duplicate the Yosemite grant during the past four years. Moreover, the rewritten paragraph concluded with an appeal to national pride. Consider "what a blessing it would be to all visitors" for these areas to be "preserved for public use," he asked, "what an honor to the Nation!"5 Widespread indifference was still a major hurdle. Especially during the nineteenth century, distance and income prohibited most Americans from ever knowing the wonders of the West firsthand. Nor could literature alone bring its wonderlands within reach. As a result, landscape painters and photographers were equally important in furthering the spirit of concern that led to the national park idea. Foremost among artists to portray the region were Albert Bierstadt and Thomas Moran, whose works gave impetus to the establishment of Yosemite and Yellowstone parks respectively.6 Indeed, the success of scenic protection depended on visual proof of the uniqueness of western landmarks. Once their beauty had been confirmed by artists as well as nationalists, Congress responded favorably to pleas that the most renowned wonderlands should be set aside, first as symbols of national pride and, in time, as areas for public recreation. The reliance on nature as proof of national greatness began in earnest immediately following American independence from Great Britain. A clearly undesirable side effect of political freedom was the rending of former ties with European culture. No longer could the United States lay claim to the achievements of Western civilization merely by recalling its membership in the British Empire. In recognition of this disquieting fact, patriots tried to reassure themselves that the United States was destined for a grand and glorious future in its own right. Yet doubts were bound to persist, especially when American intellectuals dared to consider whether or not their culture really could survive apart from Europe. Since the achievements of their own artists and writers were negligible, nationalists turned to nature as the only viable alternative. As early as 1784, for example, Thomas Jefferson singled out portions of the American landscape to support his conviction that the environment was ideal for future national attainments. He was especially proud of two wonders native to Virginia, the Natural Bridge, south of Lexington, and the Potomac River Gorge, which pierces the Blue Ridge Mountains at Harpers Ferry. High above the river, on a large rock later named in his honor, he declared the panorama of rapids and cliffs "worth a voyage across the Atlantic."7 Other essayists were far less restrained. Philip Freneau, for example, focused his defense of national pride farther westward, where he crowned the Mississippi the "prince of rivers, in comparison of whom the Nile is but a small rivulet, and the Danube a ditch."8 Even the most spirited nationalists, however, could not be blind to the obvious distortions of such claims. That the Danube was not a ditch went without saying. And why should Europeans risk the long and dangerous Atlantic crossing just to see the Potomac River, especially when the Old World possessed its equivalent—or better—in the scenery of the Rhine? Clearly Americans had to do more than stretch reality if Europeans were to concede any validity to the New World point of view. Unfortunately for America's nationalists, their subsequent attempts to distinguish the United States from Europe through the medium of nature proved no more convincing. Landscapes in the New World were simply too lacking in history for those many intellectuals who longed for stronger emotional attachments to their culture than great rocks, waterfalls, or rivers. Few voiced their doubts more poignantly than Washington Irving. In 1819 he confided to his Sketch Book that he preferred "to wander over the scenes of renowned achievement—to tread, as it were, in the footsteps of antiquity—to loiter about the ruined castle—to meditate on the falling tower—to escape, in short, from the commonplace reality of the present, and lose myself among the shadowy grandeurs of the past." Thus Irving was among those who satisfied his fantasies abroad, although he conceded that no American need "look beyond his own country for the sublime and beautiful of natural scenery."9 Irving's qualification, however, was little more reassuring than nationalists' prior distortions. At best it allowed the United States to claim equality with European landscapes only in the category of visual impact. This did nothing to ease the discomfort of those who still struggled to link American scenery with deeply emotional and spiritual values as well. In this vein James Fenimore Cooper revealed the inner misgivings of everyone concerned when he admitted their dilemma was beyond resolution until civilization in the New World had also advanced to "the highest state." Meanwhile Americans must "concede to Europe much the noblest scenery...in all those effects which depend on time and association."10 Shortly before his death, in September 1851, Cooper still maintained that "the great distinction between American and European scenery, as a whole," lay "in the greater want of finish in the former than in the latter, and to the greater superfluity of works of art in the old world than in the new." Specifically, European landscapes included castles, fortified towns, villages accented by towering cathedrals, and similar "picturesque and striking collections of human habitations." Although nature had "certainly made some differences" between the two continents, still no one could deny Europe's superiority over the United States in the possession of landscapes blessed with "the impress of the past."11 First published in The Nation, Cooper's assessment later appeared in The Home Book of the Picturesque. Among the volume's other contributors were William Cullen Bryant, Washington Irving, and Nathaniel Parker Willis, all of whom had achieved prominence in writings about the American scene. Indeed no book contains a more comprehensive overview of the anxieties aroused by America's search for distinction through landscape. Cooper's daughter, Susan, for example, who also contributed to the collection of articles, likewise revealed the depth of misgivings about the sense of impermanence and instability in a typical northeastern landscape. One "soft hazy morning, early in October," she began, "we were sitting upon the trunk of a fallen pine, near a projecting cliff which overlooked the country for some fifteen miles or more; the lake, the rural town, and the farms and valleys beyond, lying at our feet like a beautiful map." Yet when she compared the scene below to similar examples in Europe, her cheerfulness faded. Suddenly the taverns and shops of the village only reminded her of the "comparatively slight and furtive character of American architecture." Indeed, she said, echoing her father's lament, "there is no blending of the old and new in this country; there is nothing old among us." Even if Americans were "endowed with ruins"—her bitterness grew—"we should not preserve them"; rather "they would be pulled down to make way for some novelty." She could only imagine that the village had been miraculously transformed into an Old World hamlet, but this fantasy, too, failed in the least to comfort her. Forced to abandon her daydream, her visionary bridge "of massive stone, narrow, and highly arched," the "ancient watch-tower" rising above the trees, and the old country houses and thatched-roof cottages all vanished into nothingness. Her spell broken, "the country resumed its every-day aspect."12