CELEBRATING THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CENTENNIAL • 1916-2016

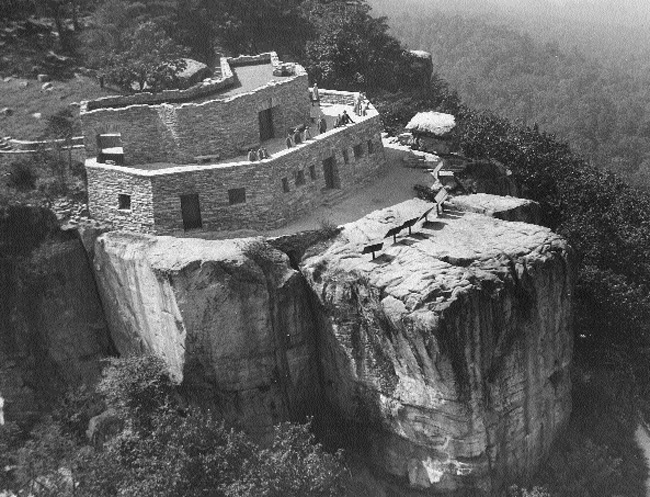

Bryce Canyon National Park

|

NPS Centennial Monthly Feature

This month we explore another key component of National Park Service management: cultural resource management (CRM). Part of the National Park Service mandate, as outlined in the NPS Organic Act, is to conserve both "the natural and historic objects" (emphasis added). We begin by briefly outlining some of the modern-day programs the National Park Service has developed to perform cultural resource management responsibilties. The American Battlefield Protection Program (ABPP) promotes the preservation of significant historic battlefields associated with wars on American soil. The goals of the program are 1) to protect battlefields and sites associated with armed conflicts that influenced the course of our history, 2) to encourage and assist all Americans in planning for the preservation, management, and interpretation of these sites, and 3) to raise awareness of the importance of preserving battlefields and related sites for future generations. The ABPP focuses primarily on land use, cultural resource and site management planning, and public education. The Archeology Program has archeologists at work throughout the national park system, though an essential part of the effort is ensuring that sites are not disturbed by visitors, thieves, erosion, or other forces. As outlined in the Director's Order #28A: Archeology: As one of the principal stewards of America's heritage, the NPS is charged with the preservation of the commemorative, educational, scientific, and traditional cultural values of archeological resources for the benefit and enjoyment of present and future generations. The Service does this through (1) archeological resource stewardship within the national parks, and (2) assistance to partners, including Federal, State, tribal, and local government agencies; individuals; and private organizations outside the national parks. The Cultural Anthropology Program harnesses the power of research and communication to connect cultural communities with places that are considered essential to their identity. Since 1981, the NPS has developed a diverse network of practicing cultural anthropologists in parks, regional offices and a national program office in Washington DC. These anthropologists apply new knowledge and current anthropological methods to connect parks and people. Together with its parent organization the NPS Tribal Relations and American Cultures (TRAC) Program, and co-workers in the Park NAGPRA Program, Tribal Historic Preservation Program, and Cultural Resources Office of Interpretation and Education, the Cultural Anthropology Program ensures living people - linked to parks by deep historical or cultural attachments - have a voice in agency decision-making. The Federal Preservation Institute (FPI) was established by the National Park Service in 2000. FPI provides historic preservation training and education materials for use by all federal agencies and preservation officers. FPI's mission is mandated by Section 101(j) of the National Historic Preservation Act that directs the Secretary of the Interior to implement a comprehensive preservation education and training program that provides new standards and increased training opportunities. FPI administers the Secretary of the Interior's preservation award program for Federal, Tribal, and State Historic Preservation Offices, and Certified Local Governments. The Heritage Documentation Programs administers the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS), the Federal Government's oldest preservation program, and its companion programs: the Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) and Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS). Documentation produced through the programs constitutes the nation's largest archive of historic architectural, engineering, and landscape documentation. The HABS/HAER/HALS Collection is housed at the Library of Congress. The Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) is the nation's first federal preservation program, begun in 1933 to document America's architectural heritage. Creation of the program was motivated primarily by the perceived need to mitigate the negative effects upon our history and culture of rapidly vanishing architectural resources. At the same time, important early preservation initiatives were just getting underway, such as restoration of the colonial capital at Williamsburg and the development within the National Park Service (NPS) of historical parks and National Historic Sites. Architects interested in the colonial era had previously produced drawings and photographs of historic architecture, but only on a limited, local, or regional basis. A source was needed to assist with the documentation of our architectural heritage, as well as with design and interpretation of historic resources, that was national in scope. As it was stated in the tripartite agreement between the American Institute of Architects, the Library of Congress, and the NPS that formed HABS: 1) A comprehensive and continuous national survey is the logical concern of the Federal Government; 2) As a national survey, the HABS collection is intended to represent; 3) a complete resume of the builder's art. Thus, the building selection ranges in type and style from the monumental and architect-designed to the utilitarian and vernacular, including a sampling of our nation's vast array of regionally and ethnically derived building traditions. The Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) was established in 1969 by the National Park Service, the American Society of Civil Engineers and the Library of Congress to document historic sites and structures related to engineering and industry. This agreement was later ratified by four other engineering societies: the American Society of Mechanical Engineers, the Institute of Electrical and Electronic Engineers, the American Institute of Chemical Engineers, and the American Institute of Mining, Metallurgical and Petroleum Engineers. Appropriate subjects for documentation are individual sites or objects, such as a bridge, ship, or steel works; or larger systems, like railroads, canals, electronic generation and transmission networks, parkways and roads. HAER developed out of a close working alliance between the Historic American Buildings Survey (HABS) and the Smithsonian Institution's (SI) Museum of History and Technology (now the Museum of American History). From its inception, HAER focused less on the building fabric and more on the machinery and processes within, although structures of distinctly industrial character continue to be recorded. As the most ubiquitous historic engineering structure on the landscape, bridges have been a mainstay of HAER recording; HABS also documented more than 100 covered bridges prior to 1969. In recent years, maritime documentation has become an important program focus. The Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) mission is to record historic landscapes in the United States and its territories through measured drawings and interpretive drawings, written histories, and large-format black and white photographs and color photographs. The National Park Service oversees the daily operation of HALS and formulates policies, sets standards, and drafts procedural guidelines in consultation with the American Society of Landscape Architects (ASLA). The ASLA provides professional guidance and technical advice through their Historic Preservation Professional Practice Network. The Prints & Photographs Division of the Library of Congress preserves the documentation for posterity and makes it available to the general public. As documentation has expanded from strictly buildings to engineering sites and processes, it is natural to further broaden recording efforts to include landscapes. With the growing vitality of landscape history, preservation and management, proper recognition for historic American landscape documentation must be addressed. In response to this need, the American Society of Landscape Architects Historic Preservation Professional Interest Group worked with the National Park Service to establish a national program. Hence, in October 2000 the National Park Service permanently established the Historic American Landscapes Survey (HALS) program for the systematic documentation of historic American landscapes. The Historic Preservation Internship Training Program trains our future historic preservation professionals. The internship program offers undergraduate and graduate students the opportunity to gain practical experience in cultural resource management programs in the National Park Service headquarters, field offices, and parks, and in other federal agencies. Working under the direction of experienced historic preservation professionals, students undertake short-term research and administrative projects. Students learn about and contribute to the national historic preservation programs and the federal government's preservation and management of historic properties. The Historic Preservation Planning Program develops national policy related to historic preservation planning. Preservation planning is the rational, systematic process by which a community develops a vision, goals, and priorities for the preservation of its historic and cultural resources. The community seeks to achieve its vision through its own actions and through influencing the actions of others. Goals and priorities are based on analyses of resource data and community values. The Historic Preservation Planning Program helps communities of all kinds make sense of the planning process and ensure it is useful and effective. The goals of the Historic Preservation Planning Program are to: a) strengthen the integration of historic preservation into the broader public policy and land-use planning and decision-making arenas at the federal, state, tribal, and local levels; b) increase the opportunities for broad-based and diverse public participation in planning for historic and cultural resources; c) expand knowledge and skills in historic preservation planning; and d) assist states, tribes, local governments, and federal agencies in carrying out inclusive preservation planning programs that are responsive to their own needs and concerns. The Historic Surplus Property Program enables state, county, and local governments to obtain historic buildings once used by the Federal government at no cost and to adapt them for new uses. For centuries, Americans have used waterways for commerce, transportation, defense, and recreation. The Maritime Heritage Program works to advance awareness and understanding of the role of maritime affairs in the history of the United States. Through leadership, assistance, and expertise in maritime history, preservation, and archeology we help to interpret and preserve our maritime heritage by maintaining inventories of historic U.S. maritime properties, providing preservation assistance through publications and consultation, educating the public about maritime heritage through our website, sponsoring maritime heritage conferences and workshops, and funding maritime heritage projects when grant assistance is available. The National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000 (NHLPA) provides a mechanism for the disposal of Federally-owned historic light stations that have been declared excess to the needs of the responsible agency. The NHLPA recognizes the cultural, recreational, and educational value associated with historic light station properties by allowing them to be transferred at no cost to Federal agencies, State and local governments, nonprofit corporations, educational agencies, and community development organizations. These entities must agree to comply with conditions set forth in the NHLPA and be financially able to maintain the historic light station. The eligible entity to which the historic light station is conveyed must make the station available for education, park, recreation, cultural, or historic preservation purposes for the general public at reasonable times and under reasonable conditions. The Museum Management Program is charged with providing professional stewardship for more than 42 million objects and specimens and 52,400 linear feet of archives. These collections have unique associations with park cultural and natural resources, eminent figures, and park histories. Diverse collections voucher the conclusions reached in scientific studies, resource studies, and planning documents. They provide the foundation of park interpretation and education programs. They document and confirm the administrative histories of park units and the relationships with park stakeholders, and they provide the raw material for future studies by park and public researchers. Museum management consists of the policy, procedures, processes, and activities that are essential to fulfilling functions that are specific to museums, such as acquiring, documenting, and preserving collections in appropriate facilities and providing for access to and use of the collections for such purposes as research, exhibition and education. The production of exhibits, the presentation of interpretive and education programs, and the publication of catalogs, books, and Web sites featuring museum collections and themes are part of museum management. The administrative functions relating to funding, human resources, maintenance, and property management are also part of museum management and require certain knowledge and skills specific to the museum environment. The National Center for Preservation Technology and Training (NCPTT) strives to develop and distribute skills and technologies that enhance the preservation, conservation, and interpretation of prehistoric and historic resources throughout the United States. It conducts research and collaborates with partners on projects in several overlapping disciplinary areas which are organized into four program areas: Archeology & Collections, Architecture & Engineering, Historic Landscapes, and Materials Conservation. The National Heritage Area Program (NHA) furthers the mission of the National Park Service (NPS) by fostering community stewardship of our nation's heritage. The NHA program, which currently includes 49 heritage areas, is administered by NPS coordinators in Washington DC and six regional offices — Anchorage, Oakland, Denver, Omaha, Philadelphia, and Atlanta — as well as park unit staff. National Heritage Areas (NHAs) are designated by Congress as places where natural, cultural, and historic resources combine to form a cohesive, nationally important landscape. Through their resources, NHAs tell nationally important stories that celebrate our nation's diverse heritage. NHAs are lived-in landscapes. Consequently, NHA entities collaborate with communities to determine how to make heritage relevant to local interests and needs. NHAs are a grassroots, community-driven approach to heritage conservation and economic development. Through public-private partnerships, NHA entities support historic preservation, natural resource conservation, recreation, heritage tourism, and educational projects. Leveraging funds and long-term support for projects, NHA partnerships foster pride of place and an enduring stewardship ethic. NHAs are not national park units. Rather, NPS partners with, provides technical assistance, and distributes matching federal funds from Congress to NHA entities. NPS does not assume ownership of land inside heritage areas or impose land use controls. National Historic Landmarks (NHLs) are nationally significant historic places designated by the Secretary of the Interior because they possess exceptional value or quality in illustrating or interpreting the heritage of the United States. Today, just over 2,500 historic places bear this national distinction. Working with citizens throughout the nation, the National Historic Landmarks Program draws upon the expertise of National Park Service staff who guide the nomination process for new Landmarks and provide assistance to existing Landmarks. The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) was enacted on November 16, 1990, to address the rights of lineal descendants, Indian tribes, and Native Hawaiian organizations to Native American cultural items, including human remains, funerary objects, sacred objects, and objects of cultural patrimony. The Act assigned implementation responsibilities to the Secretary of the Interior, and staff support is provided by the National NAGPRA Program. The National NAGRPA Program is administered by the National Park Service, a bureau of the Department of the Interior. The National Park Service has compliance obligations for parks, separate from the National NAGPRA Program. National NAGPRA is the omnibus program, the constituent groups of which are all Federal agencies, museums that receive Federal funds, tribes and Native Hawaiian organizations and the public. The National Register of Historic Places is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. Authorized by the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places is part of a national program to coordinate and support public and private efforts to identify, evaluate, and protect America's historic and archeological resources. The NPS role includes: a) Review nominations submitted by states, tribes, and other federal agencies and list eligible properties in the National Register; b) Offer guidance on evaluating, documenting, and listing different types of historic places through the National Register Bulletin series and other publications; c) Help qualified historic properties receive preservation benefits and incentives. The Park Cultural Landscapes Program serves to develop, implement, and oversee a nationwide program of cultural landscape documentation and preservation in national park units. Cultural landscapes reflect our multi-generational ties to the land, with patterns that repeat and change to remind us of the depth of our roots and the unique character of our present. They are public or private lands, large or small, that meet National Register Criteria for Evaluation for: a) historic significance(importance in the nation's history) and; b) historic integrity (physical authenticity). These places demonstrate our need to grow food, to build settlements and communities, to enjoy leisure and recreation, and to honor our deceased. Above all, these places demonstrate our continuing need to find our place within environmental and cultural surroundings. America's rich legacy is carried in its cultural landscapes; from scenic parkways to battlefields, formal gardens to cattle ranches, cemeteries to village squares, and pilgrimage routes to industrial areas. The Park History Program, begun in 1931, preserves and protects our nation's cultural and natural resources by conducting research on national parks, national historic landmarks, park planning and special history studies, oral histories, and interpretive and management plans. Our staff helps evaluate proposed new parks, and we support cultural resources personnel in parks, regional offices, and Washington in all matters relating to the history and mission of the Park Service. Located in Washington and led by the chief historian, the program offers a window into the historical richness of the National Park System and the opportunities it presents for understanding who we are, where we have been, and how we as a society, might approach the future. The State, Tribal, and Local Plans & Grants Division provides preservation assistance through a number of programs that support the preservation of America's historic places and diverse history. We administer grant programs to State, Territorial, Tribal, and local governments, educational institutions, and non-profits in addition to providing preservation planning, technical assistance, and policy guidance. Our work supports historic properties and place-based identity, key components to the social and economic vitality of our communities. The National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended through 2006, the foundation for our programs, declares that: a) the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon and reflected in its historic heritage; b) the preservation of this irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest so that its vital legacy of cultural, educational, aesthetic, inspirational, economic, and energy benefits will be maintained and enriched for future generations of Americans. Established in 1977, the Historic Preservation Fund (HPF) is the funding source of the preservation awards to the States, Tribes, local governments, and non-profits. Authorized at $150 million per year, the funding is provided by Outer Continental Shelf oil lease revenues, not tax dollars. The HPF uses revenues of a non-renewable resource to benefit the preservation of other irreplaceable resources. Teaching with Historic Places (TwHP) uses properties listed in the National Park Service's National Register of Historic Places to enliven history, social studies, geography, civics, and other subjects. TwHP has created a variety of products and activities that help teachers bring historic places into the classroom. Technical Preservation Services develops historic preservation standards and guidance on preserving and rehabilitating historic buildings, administers the Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives Program for rehabilitating historic buildings, and sets the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties. The Tribal Preservation Program assists Indian tribes in preserving their historic properties and cultural traditions through the designation of Tribal Historic Preservation Offices (THPO) and through annual grant funding programs. The program originated in 1990, when Congress directed NPS to study and report on Tribal preservation funding needs. The findings of that report provided the foundation for this program and for the establishment of the grants programs. In 1996, twelve tribes were approved by the Secretary of the Interior and NPS to assume the responsibilities of a Tribal Historic Preservation Office (THPO) on tribal lands, pursuant to Section 101(d) of the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended. The number of designated THPOs has grown to more than 140 in 2012, and continues to grow at an accelerated pace. Two important grant programs are funded through the Historic Preservation Fund: a) formula grants to the Tribal Historic Preservation Offices, and; b) the competitive Tribal Project Grants to Federally recognized tribes, Alaskan Natives and Native Hawaiian organizations. (Source: nps.gov) Interestingly, a comprehensive history of past duties has yet to be written, but we conclude this review by drawing upon two studies written by Richard West Sellars: "Pilgrim Places: Civil War Battlefields, Historic Preservation, and America's First National Military Parks, 1863-1900" (from CRM: The Journal of Cultural Resource Management, vol. 2 no. 1, Winter 2005), which covers the early creation of CRM in the East and "A Very Lare Array: Early Federal Historic Preservation — The Antiquities Act, Mesa Verde, and the National Park Service Act" (from National Resources Journal, vol. 47 no. 2, Spring 2007, reproduced with permission from the University of New Mexico School of Law), which explors the early creation of CRM in the West. For additional insights into cultural resource management, you are invited to read these additional books. Pilgrim Places: Civil War Battlefields, Historic Preservation, and America's First National Military Parks, 1863-1900 Richard West Sellars Today, well over a century after the Civil War ended in 1865, it is difficult to imagine the battlefields of Antietam, Vicksburg, Shiloh, Gettysburg, Chickamauga, and Chattanooga had they been neglected, instead of preserved as military parks. As compelling historic landscapes of great natural beauty and public interest, these early military parks (established by Congress in the 1890s and transferred from the United States War Department to the National Park Service in 1933) have been familiar to generations of Americans. Their status as preserved parks is far different from what would have ensued had they been left to the whims and fluctuations of local economics and developmental sprawl, with only a military cemetery and perhaps one or two monuments nearby. Certainly, had these battlefields not been protected, the battles themselves would still have been intensively remembered, analyzed, and debated in countless history books, classrooms, living rooms, barrooms, and other venues. But there would have been little, if any, protected land or contemplative space in which to tell the public that these are the fields upon which horrific combat occurred—battles that bore directly on the perpetuation of the nation as a whole, and on the very nature of human rights in America. Yet in the final decade of the 19th century, Congress mandated that these battlefields be set aside as military parks to be preserved for the American public. The sites became major icons of the nation's historic past, to which millions of people have traveled, many as pilgrims, and many making repeated visits—ritualistic treks to hallowed shrines. How, then, did these battlefields, among the most important of the Civil War, become the nation's first national military parks?

Gettysburg and the Stratigraphy of History For the first three days of July 1863, more than 170,000 soldiers of the United States Army (the Union army) and the Confederacy fought a bloody and decisive battle around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, ending with a Union victory and with more than 51,000 killed, wounded, and missing. Later that month, less than three weeks after the battle, David McConaughy, a local attorney, began efforts to buy small segments of the battlefield, where grim evidence of combat still lay on the devastated landscape, and the stench of death from both soldiers and horses remained in the air. A long-time resident and civic leader in Gettysburg, McConaughy was seeking to preserve the sites and protect them from possible desecration and land speculation prompted by the intense interest in the battle. He also acquired a small segment of the battleground that seemed appropriate as a burial site for those soldiers of the Union army whose bodies would not be carried back to their home towns or buried elsewhere. The plan to establish a military cemetery simultaneously gained support from other influential individuals and would soon meet with success. But it was McConaughy who took the initial step that would ultimately lead to preserving extensive portions of the battlefield specifically for their historical significance. McConaughy later recalled that this idea had come to him "immediately after the battle." And as early as July 25, he wrote to Pennsylvania governor Andrew Curtin, declaring his intentions. He recommended entrusting the battlefield to the public: that the citizens of Pennsylvania should purchase it so that "they may participate in the tenure of the sacred grounds of the Battlefield, by contributing to its actual cost." By then, McConaughy had secured agreements to buy portions of renowned combat sites such as Little Round Top and Culp's Hill. In August, he led in the creation of the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association to oversee the acquisition and protection of the battleground. (He would later sell the lands he had purchased to the cemetery and to the Memorial Association, at no personal profit.) Also in August, he reiterated what he had told Governor Curtin, that there could be "no more fitting and expressive memorial of the heroic valor and signal triumphs of our army...than the battlefield itself, with its natural and artificial defen[s]es, preserved and perpetuated in the exact form and condition they presented during the battle."1 David McConaughy's decisive response to the battle was pivotal: It marked the pioneer effort in the long and complex history of the preservation of America's Civil War battlefields that has continued through the many decades since July 1863. With the support of the State of Pennsylvania, the Memorial Association's purchase of battlefield lands got under way, albeit slowly. Acquisition of land specifically intended for the military cemetery continued as well, beyond what McConaughy had originally purchased for that purpose. At Gettysburg, despite the carnage and chaotic disarray on the battlefield after the fighting ended, care for the dead and wounded could be handled with relatively moderate disruption and delay, given the Confederate army's retreat south. Re-burial of Union soldiers' bodies lying in scattered, temporary graves began by late October in the military cemetery. And on November 19, President Abraham Lincoln gave his dedication speech for the new cemetery. Surely the most famous public address in American history, Lincoln's Gettysburg Address became the symbolic touchstone for the remarkable succession of commemorative activities that would follow at the battlefield. In his brief comments, Lincoln stated what he believed to be an "altogether fitting and proper" response of the living: to dedicate a portion of the battlefield as a burying ground for the soldiers who sacrificed their lives at Gettysburg to preserve the nation. Lincoln then added, "But, in a larger sense, we can not dedicate—we can not consecrate—we can not hallow—this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it, far above our poor power to add or detract."2 Yet in attending the dedication and giving his address, Lincoln himself participated in—and helped initiate—a new era of history at the battlefield, one in which both his and future generations would perpetuate the dedication, consecration, and hallowedness of the site. The history of the Battle of Gettysburg differs from the history of Gettysburg Battlefield. The first is military history—the cataclysmic battle itself, when Union forces thwarted the Southern invasion of Northern territory in south-central Pennsylvania. The second—the complex array of activities that have taken place on the battlefield in the long aftermath of the fighting—is largely commemorative history: this country's efforts to perpetuate and strengthen the national remembrance of Gettysburg, including McConaughy's preservation endeavors, the cemetery dedication, and Lincoln's address. After dedication of the cemetery, the nation's response to the battle continued, through such efforts as acquiring greater portions of the field of battle, holding veterans' reunions and encampments, erecting monuments, and preserving and interpreting the battlefield for the American people. Most of these activities have continued into the 21st century. In the deep "stratigraphy" of history at Gettysburg Battlefield—decade after decade, layer after layer, of commemorative activity recurring at this renowned place—no other single event holds greater significance than Lincoln's address contemplating the meaning of the Battle of Gettysburg and of the Civil War. And in April 1864—well before the war ended—commemoration at the battlefield was further sanctioned when the State of Pennsylvania granted a charter to the already established Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association to oversee and care for the field of battle. The charter's declaration "to hold and preserve the battle-grounds of Gettysburg...with the natural and artificial defenses, as they were at the time of said battle," and to perpetuate remembrance of the battle through "such memorial structures as a generous and patriotic people may aid to erect" very much reflected McConaughy's own convictions, as stated the previous summer.3 The act chartering the nonprofit Memorial Association and authorizing its acquisition, preservation, and memorialization of the battlefield was passed in a remarkably short period of time—about 10 months after the battle itself. It set a course toward common, nonprofit ownership of the battlefield for patriotic inspiration and education. Moreover, as battlefield commemoration evolved, the town of Gettysburg prospered economically from the public's increasing desire to visit the site. Almost immediately after the fighting ended, the hundreds of people who poured into the area to seek missing relatives or assist with the wounded and dead created further chaos in and around the town. But many who came were simply curious about the suddenly famous battlefield, and their visits initiated a rudimentary tourism that would evolve and greatly increase over the years. As soon as they could, entrepreneurs from Gettysburg and elsewhere began to profit from the crowds, marketing such necessities as room and board, in addition to selling guided tours, battlefield relics, and other souvenirs. Gettysburg's tourism would expand in the years after the war, secured by the fame of the battlefield, but also re-enforced by such added attractions as new hotels, a spa, and a large amusement area known as Round Top Park. African American tourists joined the crowds at Gettysburg beginning in the 1880s. And improved rail service to Gettysburg in 1884 greatly enhanced access from both the North and South, further increasing tourism. One guidebook estimated that 150,000 visitors came in the first two years after the new rail service began.4

Located in Pennsylvania, far from the main theaters of war, and the site of a critical and dramatic Union victory that repulsed the invasion of the North by the Confederate forces under General Robert E. Lee, the battlefield at Gettysburg clearly had the potential to inspire creation of a shrine to the valor and sacrifices of Union troops. The conditions were just right: Gettysburg quickly emerged as a hallowed landscape for the North, as it ultimately would for the nation as a whole.(Figure 2) In the beginning, the commemoration at Gettysburg was strictly limited to recognizing the Northern victory by preserving only Union battle lines and key positions. It was of course unthinkable to preserve battle positions of the Rebel army, with whom war was still raging. The Memorial Association's many commemorative activities would provide a singularly important example for other Civil War battlefields, as thousands of veterans backed by their national, state, and local organizations would, especially in the 1890s, initiate similar efforts to preserve sites of other major engagements. By that time, the North and South were gradually reconciling their differences in the aftermath of a bitter and bloody war that took the lives of more than 600,000 combatants. This growing sectional harmony brought about greater injustice against former slaves. But with reconciliation underway, the South would join in the battlefield commemoration. The Civil War remains perhaps the most compelling episode in American history, but especially during the latter decades of the 19th century it was an overwhelmingly dominant historical presence that deeply impacted the lives and thoughts of millions of Americans. In the century's last decade, Congress responded to pressure from veterans and their many supporters, both North and South, by establishing five military parks and placing them under War Department administration for preservation and memorialization—actions intended to serve the greater public interest. Known also as battlefield parks, these areas included Chickamauga and Chattanooga (administratively combined by the congressional legislation), in Georgia and Tennessee, in 1890; Antietam, near the village of Sharpsburg, Maryland, also in 1890; Shiloh, in southwestern Tennessee, in 1894; Gettysburg, transferred from the Memorial Association to the Federal Government in 1895; and Vicksburg, in Mississippi, in 1899.5 Of these battlefields set aside for commemorative preservation, the South had won only at Chickamauga.

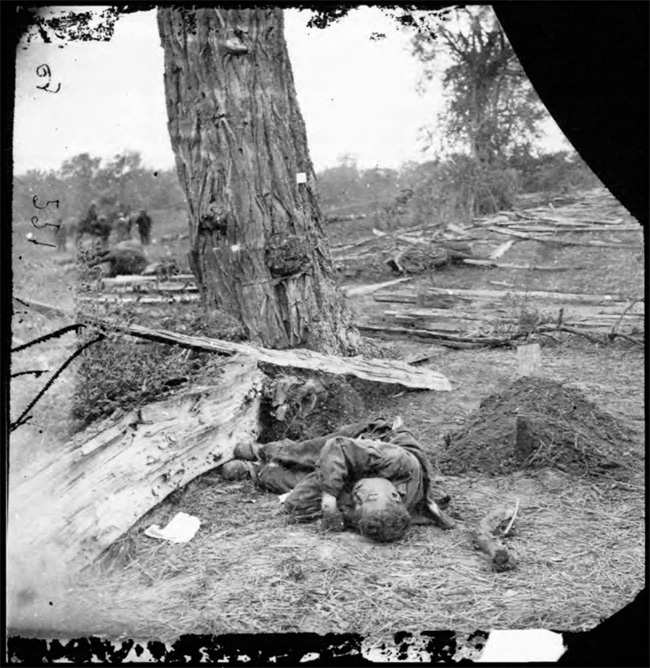

Beginning at Gettysburg even during the war and rapidly accelerating in the 1890s, the efforts to preserve the first five Civil War military parks constituted by far the most intensive and widespread historic preservation activity in the United States through the 19th century. The battlefield parks substantially broadened the scope of preservation. Background: Pre-Civil War Preservation Endeavors The event in American history prior to the Civil War that had the most potential to inspire the preservation of historic places was the American Revolution. Yet, between the Revolution and the Civil War, historic site preservation in America was limited and sporadic. The efforts that were made focused principally on the Revolution and its heroes, but also on the early national period. Even with a growing railway system, poor highways and roads still hindered travel; thus, for most Americans, commemoration of historic sites was mainly a local activity. Celebrations of historic events and persons (especially at the countless gatherings held on the Fourth of July) included parades, patriotic speeches, and, at times, the dedication of monuments in cities and towns. It is significant also that the Federal Government—which was far less powerful than it would become during and after the Civil War—was uncertain about the need for, and the constitutionality of, preserving historic sites or erecting monuments in the new republic at government expense. It therefore restricted its involvement, leaving most proposals to state or local entities, whether public or private. The State of Pennsylvania, for example, had plans to demolish Independence Hall—where the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution were debated and drawn up—to make way for new construction. But the City of Philadelphia (the local, not the national government) interceded in 1818 and purchased the building and its grounds out of patriotic concern. During the 19th century, George Washington, revered hero of the Revolution and first president of the United States, received extraordinary public acclaim, which resulted in the preservation of sites associated with his life and career. In 1850, following extended negotiations, the State of New York established as a historic-house museum the Hasbrouck House in the lower Hudson Valley— General Washington's headquarters during the latter part of the war. Mount Vernon, Washington's home along the Potomac River and the most famous site associated with his personal life, became the property of a private organization, the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association of the Union. Ann Pamela Cunningham, a determined Charlestonian, founded the Association in 1853 to gain nationwide support to purchase this site, which was accomplished in 1858. The Ladies' Association's success with Mount Vernon ranks as the nation's most notable historic preservation effort in the antebellum era.6 Among the efforts of pre-Civil War Americans to commemorate their history, erecting monuments to honor and preserve the memory of important events and persons was at times viewed as being a more suitable alternative than acquiring and maintaining a historic building and its surrounding lands. Only a few days after the defeat of the British army at Yorktown in October 1781, the Continental Congress passed a motion calling for a monument to be built on the Yorktown battle site to commemorate the French alliance with the colonies and the American victory over the British. The Congress, however, being very short of funds and focusing on the post-Revolutionary War situation, did not appropriate monies for the monument. Interest eventually waned, and construction did not get under way until a century later, with the laying of the cornerstone for the Yorktown Victory Monument during the centennial celebration in 1881. The tall, ornate granite monument was completed three years later. The effort to erect a monument to commemorate the 1775 Battle of Bunker Hill, in the Boston area, was not begun until shortly before the 50th anniversary of the battle, but unlike Yorktown it did not have to wait a century for completion. Only two years after the 1823 founding of the Bunker Hill Monument Association to spearhead the project, the cornerstone was laid by the aging Marquis de Lafayette, esteemed French hero of the American Revolution. Delayed by funding shortages and other factors, completion of the monument came in 1843. Construction of the Washington Monument in the nation's capital also encountered lengthy delays, including the Civil War. Begun in 1848, the giant obelisk was not completed until 1885.7 These and other commemorative activities did not reflect any intense interest on the part of 19th-century Americans in the physical preservation and commemoration of historic sites. Only after extended delays were the efforts with the Yorktown and Washington monuments successful. The lengthy struggle in Boston to preserve the home of John Hancock, the revered patriot and signer of the Declaration of Independence, failed, and the building was demolished. Even the State of Tennessee's acquisition in the 1850s of The Hermitage, Andrew Jackson's home near Nashville, did not guarantee preservation. The State considered selling the house and grounds long before the property finally gained secure preservation status by about the early 20th century. Partly because of cost considerations, Congress had rejected petitions to purchase Mount Vernon before the Ladies' Association was formed. And despite national adoration of George Washington, numerous obstacles (including inadequate funding) delayed the Association's purchase of the property for about half of a decade. Overall, during much of the century, a lack of funding and commitment undercut many preservation efforts, indicating a general indifference toward historic sites.8 Nevertheless, during the 19th century, an important concept gradually gained acceptance: That, in order to protect historic sites deemed especially significant, it might be necessary to resort to a special type of ownership (a public, or some other kind of shared, or group, ownership, such as a society or association) specifically dedicated to preservation. Such broad-based, cooperative arrangements could serve as a means of preventing a site from being subject to, and perhaps destroyed as a result of, the whims of individuals and the fluctuations of the open market. Private, individually owned and preserved historic sites, some exhibited to the public (but vast numbers of them preserved because of personal or family interest alone), would become a widespread, enduring, and critically important aspect of American historic preservation. Still, the State of New York's preservation of the Hasbrouck House, and especially the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association's successful endeavors, exemplified the potential of group ownership, both public and private, in helping to secure enduring preservation commitments. As one supporter stated during the effort to preserve Mount Vernon, the revered home and nearby grave of the Revolutionary War hero and first president should not be "subject to the uncertainties and transfers of individual fortune." The Mount Vernon Ladies' Association, as a remarkably enterprising and broad-based organization determined to preserve Washington's home and grave site, held the promise of a dedication to its cause that could remain steadfast well beyond one or two generations. Living up to this promise meant that the Ladies' Association would become an acclaimed archetype of a successful, cooperative preservation organization. Furthermore, the Ladies' Association's goals focused squarely on serving the greater public good: it would make the home and grounds accessible to the public, in the belief that generations of people might visit the site and draw inspiration from Washington's life that would foster virtuous citizenship, benefiting the entire nation. Explicitly revealing the concern for a guarantee of public access, a collection of correspondence relating to the Ladies' Association's effort to acquire Mount Vernon was entitled, "Documents Relating to the Proposed Purchase of Mount Vernon by the Citizens of the United States, in Order that They May at All Times Have a Legal and Indisputable Right to Visit the Grounds, Mansion and Tomb of Washington."9 Similarly, concerns for public access and benefit, ensured by dedicated common ownership, would become key factors underlying the Civil War battlefield preservation movement in the latter decades of the century. The Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, the first organizational effort to preserve and commemorate a Civil War battlefield, clearly intended to render the battleground accessible to the people and thereby serve the public good through patriotic inspiration and education. Moreover, battlefield preservation came to involve local and state governments, and ultimately the Federal Government, as representatives of the collective citizenry in the direct ownership and administration of selected historic places. Civil War Battlefield Monuments and Cemeteries As with the southern Pennsylvania countryside surrounding the town of Gettysburg, the struggles between the United States and Confederate armies from 1861 to 1865 often brought war to beautiful places, with many battles fought in the pastoral landscapes of eastern, southern, and middle America— in rolling fields and woods, along rivers and streams, among farmsteads, and often in or near villages, towns, or cities. Following the furious, convulsive battles, the armies often moved on toward other engagements, or to reassess and rebuild. They left behind landscapes devestated by the violence and destruction of war, yet suddenly imbued with meanings more profound than mere pastoral beauty. The battlefields would no longer be taken for granted as ordinary fields and wooded lands. For millions of Americans, intense emotions focused on these sites, so that while local farmers and villagers sought to recover from the devastation, the battlegrounds, in effect, lay awaiting formal recognition, perhaps sooner or later to be publicly dedicated, consecrated, and hallowed. Once the scenes of horrendous bloodletting, the preserved battlefield parks, green and spreading across countrysides ornamented with monuments, would come to form an enduring, ironic juxtaposition of war and beauty, forever paradoxical.

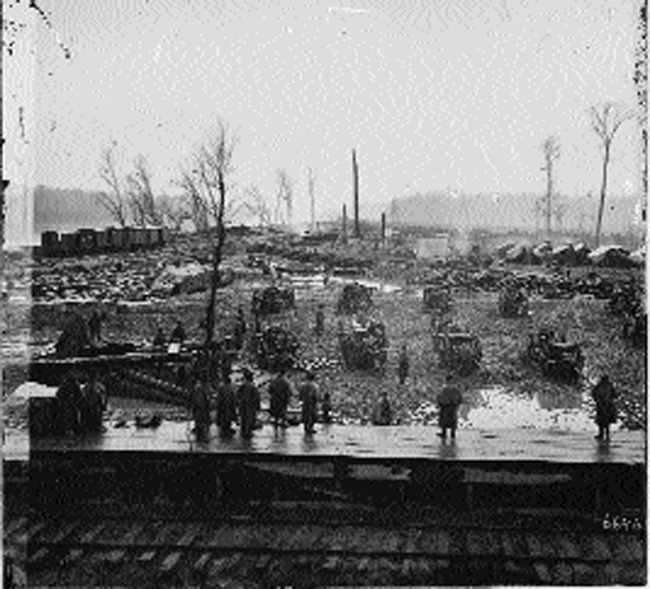

And the carefully tended battlefields remain forever beguiling: The tranquil, monumented military parks mask the horror of what happened there. Walt Whitman, whose poetry and prose include what are arguably the finest descriptions of the effects of Civil War battles on individual soldiers, wrote that the whole fratricidal affair seemed "like a great slaughter house...the men mutually butchering each other." He later asserted that the Civil War was "about nine hundred and ninety-nine parts diarrhea to one part glory." Having spent much of the war nursing terribly wounded soldiers in the Washington military hospitals and seeing sick and dying men with worm-infested battle wounds and amputations that had infected and required additional cutting, Whitman knew well the grisly costs of battle. The poet encountered many soldiers who seemed demented and wandered in a daze about the hospital wards. To him, they had "suffered too much," and it was perhaps best that they were "out of their senses." To the unsuspecting person, then, the serene, monumented battlefields can indeed belie the appalling bloodletting that took place there. Yet from the very first, it was intended that the battlegrounds become peaceful, memorial parks—each, in effect, a "pilgrim-place," as an early Gettysburg supporter put it.10 The historical significance of the first five Civil War battlefield parks was undeniably as the scenes of intense and pivotal combat, but by the early 20th century they also marked the nation's first true commitment to commemorating historic places and preserving their historic features and character. Restoration of the battle scenes, such as maintaining historic roads, forests, fields, and defensive earthworks, was underway, to varying degrees, at the battlefield parks. The parks were also becoming extensively memorialized with sizable monuments and many smaller stone markers, along with troop-position tablets (mostly cast iron and mounted on posts) tracing the course of battle and honoring the men who fought there. Erected mainly in the early decades of each park's existence, the monuments, markers, and tablets in the five military parks established in the 1890s exist today in astonishingly large numbers. The totals include more than 1,400 at Gettysburg, approximately 1,400 at Chickamauga and Chattanooga, and more than 1,300 at Vicksburg. Following these are Shiloh, with more than 600, and Antietam with more than 400. The overall total for the five battlefields is nearly 5,200.11 Although tablets and markers comprise the greatest portion of these totals, the battlefields have become richly ornamented with memorial sculpture, including many large, impressive monuments. Altogether, they are the most striking visual features of the military parks, and they provide the chief physical manifestation of the battlefields' hallowedness. The early Civil War military parks are among the most monumented battlefields in the world. Virtually all of the monuments were stylistically derivative, many inspired by classical or renaissance memorial architecture, with huge numbers of them portraying standing soldiers, equestrian figures, or men in battle action. They recall heroism, the physical intensity of battle, and grief—rather than, for instance, the emancipation of the slaves, a major result of the battles and the war. From early on, some critics have judged the monuments to be too traditional and noted that many were essentially mass-produced by contractors.12 Nevertheless, with veterans themselves directly involved in the origin and evolution of the Civil War battlefield memorialization movement, the earlier monuments reflect the sentiments of the very men who fought there. And the veterans were highly unlikely to be artistically avant-garde; rather, they tended to follow the styles and tastes of the time. Even while the war was ongoing, soldiers erected several monuments on battlefields. In early September 1861, less than five months after the April 12th firing on Fort Sumter, Confederate soldiers erected the first Civil War battlefield monument, at the site of the Battle of Manassas, near the stream known as Bull Run, in Virginia. There, in July, the Confederates had surprised the United States forces (and the Northern public) with a stunning victory. Little more than six weeks later, the 8th Georgia Infantry erected a marble obelisk of modest height to honor their fallen leader, Colonel Francis S. Bartow. (Only the monument's stone base has survived; the marble obelisk disappeared possibly even before the second battle at Manassas took place in August 1862.) The Union army erected two battlefield monuments during the war. Still standing is the Hazen monument—the oldest intact Civil War battlefield monument—at Stones River National Battlefield, near the middle-Tennessee town of Murfreesboro. There, in a savage battle in late 1862 and early 1863, Northern troops forced a Confederate retreat. In about June 1863, members of Colonel William B. Hazen's brigade (men from Illinois, Indiana, Ohio, and Kentucky) began erecting a sizable cut-limestone monument to honor their fallen comrades in the very area where they had fought and died. The monument was located in a small cemetery that held the remains of the brigade's casualties. The Union army's other wartime monument, a marble obelisk, was erected on the battlefield at Vicksburg by occupying troops on July 4, 1864, to commemorate the first anniversary of the Confederate surrender of this strategic city.13 At Stones River, the Hazen monument's location in the brigade cemetery at the scene of combat testifies to the often direct connections that would evolve between military cemeteries and preserved military parks. Each of the battles had concluded with dead and wounded from both sides scattered over the countryside, along with many fresh graves containing either completely or partially buried bodies—the hurried work of comrades or special ad hoc burial details. (The wounded, many of whom died, were cared for in temporary field hospitals, including tents, homes, and other public and private buildings.) Reacting to growing public concern about the frequently disorganized handling of the Union dead, Congress, in July 1862, passed legislation authorizing "national cemeteries" and the purchase of land for them wherever "expedient." By the end of 1862, the army had designated 12 national cemeteries, principally located where Northern military personnel were or had previously been concentrated—whether at battlefields (Mill Springs, Kentucky, for instance); near army hospitals and encampments (such as in Arlington and Alexandria, Virginia); or at military posts (such as Fort Leavenworth in Kansas). All were administered by the War Department. These newly created military cemeteries were predecessors to those that would be established on other battlefields, such as Gettysburg, Vicksburg, and Antietam.14 At Gettysburg, the site selected for a military burial ground lay adjacent to the city's existing Evergreen Cemetery and along a portion of the Union battle lines on the slopes of Cemetery Hill. There, Northern forces, in desperate combat, at times hand-to-hand, had repulsed a major Confederate assault. Locating the military cemetery where Northern troops had scored a crucial victory surely heightened the symbolism and the sense of consecration and hallowedness that Lincoln reflected upon in articulating the Union cause and the meaning of the war, and in validating the "altogether fitting and proper" purpose of battlefield cemeteries. During and after the 1863 siege of Vicksburg, the Union army hastily buried thousands of its soldiers killed during the campaign. The burials, some in mass graves, were in the immediate vicinity of the siege or were scattered throughout the extensive countryside in Mississippi and in the Louisiana parishes across the Mississippi River where the campaign took place. In the chaos of battle, the army kept few burial records, left many graves unmarked, and did little to arrange for proper re-burial. At Vicksburg, as elsewhere, erosion often uncovered the bodies, making them even more vulnerable to vultures, hogs, and other scavengers. An official report in May 1866 noted that, as the Mississippi had shifted its course or spread out into the Louisiana floodplains, it carried downriver many bodies, which "floated to the ocean in their coffins or buried in the sand beneath [the river's] waters." After delays resulting from wartime pressures and protracted deliberations about where to locate an official burial ground (even New Orleans was considered), the national cemetery at Vicksburg was established in 1866, and the re-burial efforts moved toward completion.15 (Figure 3)

Antietam National Cemetery was officially dedicated on September 17, 1867, the fifth anniversary of the battle. Following Antietam's one-day holocaust, which resulted in more deaths (estimated between 6,300 and 6,500) than on any other single day of the war, most of the dead were buried in scattered locations on the field of battle, where they remained for several years. In 1864, the State of Maryland authorized the purchase of land for a cemetery. A site was selected on a low promontory situated along one of the Confederate battle lines, and re-burial of remains from Antietam and nearby engagements began in late 1866. Following contentious debate (Maryland was a border state with popular allegiance sharply divided between the North and South), it was decided that only Union dead would be buried in the new cemetery. Re-burial of Confederate dead would come later, and elsewhere.16 After the war ended, a systematic effort to care for the Northern dead led to the creation of many more military cemeteries, most of them established under the authority of congressional legislation approved in February 1867. This legislation strengthened the 1862 legal foundation for national cemeteries—for instance, by reauthorizing the purchase of lands needed for burying places; providing for the use of the government's power of eminent domain when necessary for acquiring private lands; and calling for the reimbursement of owners whose lands had been, or would be, expropriated for military cemetery sites. The total number of national cemeteries rose from 14 at the end of the war to 73 by 1870, when the re-burial program for Union soldiers was considered essentially completed. Although many of the new official burial grounds were on battlefields or military posts, others were part of existing private or city cemeteries. Also, two prominent battlefield cemeteries that had been created and managed by states were transferred to the War Department: Pennsylvania ceded the Gettysburg cemetery in 1872, and Maryland transferred the Antietam cemetery five years later.17 Of the five battlefield parks established in the 1890s, all would either adjoin or be near military cemeteries. Even as they were being established and developed, the national cemeteries stood out as hallowed commemorative sites. And they provided an early and tangible intimation that the surrounding battlefield landscapes were also hallowed places, perhaps in time to be officially recognized. The national cemeteries were thus precursors to the far larger military parks—which themselves were like cemeteries in that they still held many unfound bodies. The first of the truly large memorials on Civil War battlefields were two imposing monuments erected in national cemeteries—one at Gettysburg, the other at Antietam. In 1864, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association requested design proposals for a "Soldiers' National Monument" to be placed in the cemetery's central space, as intended in the original landscape plan. The selected design featured a tall column topped by the figure of Liberty, and a large base with figures representing War, Peace, History, and Plenty. The monument was formally dedicated in 1869. At Antietam, plans for the national cemetery also included a central space for a monument—a design feature apparently inspired by the Gettysburg cemetery plan. The contract was let in 1871 for the monument—a large, off-white granite statue of a United States Army enlisted man. Insufficient funding helped delay its completion, so that formal dedication of the "Soldiers' Monument" did not occur until 1880, on the 18th anniversary of the battle.18 Like the monuments erected during the war itself, those erected within the Gettysburg and Antietam national cemeteries were harbingers of the extensive memorialization that would in time take place in the early military parks.

In the aftermath of Union victories, most Confederate bodies were buried individually or in mass graves on the fields of battle, and most did not receive formal burials until much later. Such was the case at Gettysburg, where huge numbers of Confederate dead lay in mass graves until the early 1870s, given the Northern officials' strict prohibition of Rebel burials in the military cemetery—a restriction put in place at other Union cemeteries located on battlefields. At Shiloh, hundreds of Southern dead were buried together in trenches. (Some of these mass burials, although mentioned in official reports, have never been located.) Early in the war, well before the siege of Vicksburg got under way, the Confederate army began burying its dead in a special section of Cedar Hill, the Vicksburg city cemetery, which ultimately held several thousand military graves. And following the Confederate victory at Chickamauga, a somewhat systematic attempt to care for the bodies of Southern soldiers was disrupted by the Northern victory at nearby Chattanooga about two months later. In many instances, however, the Confederate dead were disinterred and moved by local people or by the soldiers' families for formal burial in cemeteries all across the South, including town and churchyard cemeteries. Much of this took place after the war and through the efforts of well-organized women's memorial organizations and other concerned groups and individuals.19 At Antietam, a concerted effort to remove hastily buried Rebel dead from the field of battle did not get under way until the early 1870s, about a decade after the battle. Then, over a period of several years, those remains that could be found were buried in nearby Hagerstown, Maryland. Concern that Antietam National Cemetery should in no way honor the South was made especially clear by the extended debate over "Lee's Rock," one of several low-lying limestone outcrops in the cemetery. Located on a high point along Confederate lines, the rock provided a vantage point that, reportedly, Robert E. Lee used to observe parts of the battle. After the war, the rock became a curiosity and a minor Southern icon. But Northerners viewed it as an intrusion into a Union shrine, and wanted this reminder of the Rebel army removed. The final decision came in 1868—to take away all rock outcrops in the cemetery.20 Still, this comprehensive solution makes the removal of Lee's Rock seem like an act of purification, erasing even the mere suggestion of Southern presence in the national cemetery. Reunions, Reconciliation, and Veterans' Interest in Military Parks Once the national cemeteries were established, they were effectively the only areas of the battlefields in a condition adequate to receive the public in any numbers, and they became the focal points for official ceremonies and other formal acts of remembrance. Most widely observed was Decoration Day, begun at about the end of the war in response to the massive loss of life suffered during the four-year conflict. Known in the South as Confederate Decoration Day (and ultimately, nationwide, as Memorial Day), this special time of remembrance came to be regularly observed on battlefields and in cities and towns throughout the North and South.21 As remembrance ceremonies spread across the United States and as battlefield tourism grew in the years after the war, another type of gathering also gradually got underway: the veterans' reunions. Usually held on the anniversary of a particular battle, or on Decoration Day, these reunions began early on in communities around the country. They were initiated by local or state veterans' groups, or by larger, more broadly based veterans' associations that formed after the war in both Northern and Southern states. Chief among many such associations in the North was the Grand Army of the Republic, founded in 1866 in Springfield, Illinois. Aided by, but sometimes in competition with, other Union veterans' organizations, such as the Society for the Army of the Tennessee and the Society for the Army of the Potomac, the Grand Army did not reach its period of greatest influence until the late 1870s. Due mainly to extremely difficult conditions in the postwar South, Confederate veterans organized more slowly —for instance, the establishment of the Association of the Army of Northern Virginia occurred in 1870, five years after the war. Others followed, including the United Confederate Veterans, established in 1889 and ultimately becoming the most influential Southern veterans' association. These organizations were supported by a number of women's patriotic groups, such as the United Daughters of the Confederacy and, in the North, the Woman's Relief Corps.22 Gettysburg, much as it did with national cemeteries and other commemorative efforts, played a leading role in the emergence of veterans' reunions on the battlefields. For some time after the war, few reunions were held on any battlefield, given the vivid recollections of bloodletting, the veterans' need to re-establish their lives and improve their fortunes, and the expense and logistics of traveling across country to out-of-the-way battle sites. In the summer of 1869, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association hosted a well-attended reunion of officers of the Army of the Potomac. Yet, reunions held at the battlefield in the early and mid-1870s, and open to Union veterans of any rank, attracted few. More successful was a reunion in 1878 sponsored by the Grand Army of the Republic. Two years later, the Grand Army gained political control of the Memorial Association, giving the Gettysburg organization a much stronger national base. The Memorial Association then began promoting annual reunions, including successful week-long gatherings on the battlefield between 1880 and 1894. These reunions included huge encampments: tenting again on the battlefield, with comradery such as songfests, patriotic speeches, renewal of friendships, and much reminiscing—war stories told and retold.23 The growing attendance at reunions in the 1880s increased interest in transforming Gettysburg into a fully developed military park, much as had been envisioned in the 1864 charter of the Memorial Association. Such features as monuments, avenues, and fences were to be located at, or near, key Union battle positions. By the end of the 1870s, however, little development had taken place, and the purchase of major sites by the Memorial Association had proceeded very slowly. But by the mid-1880s, with the 25th anniversary of the battle approaching, and with the Grand Army of the Republic's backing, the Memorial Association was re-energized and revived its original concept of a monumented battlefield. It encouraged new monuments to commemorate prominent officers and the many army units that fought at Gettysburg, as well as each of the Northern states whose men made up those units. Memorialization on the battlefield escalated during the last half of the decade. For example, in 1888, the 25th anniversary year, the veterans dedicated almost 100 regimental monuments. The decision to allow large numbers of monuments and markers at Gettysburg stands as a landmark in that it set a precedent for extensive memorialization in the other early military parks. In addition, by the 1890s, with greatly improved transportation and expanded middle-class leisure travel, Gettysburg Battlefield had become one of America's first nationwide historic destination sites for tourists.24 In retrospect at least, the crush of tourism and entertainment attractions that flooded into the Gettysburg area in the years after the war demonstrated a need for a protected park to prevent the onslaught of economic development from overwhelming a historic shrine. At Gettysburg, the connections that had developed between tourism and the historic battlefield foreshadowed similar relationships that would be a continuous and important factor in many future historic preservation endeavors, both public and private. Surely during the Civil War, the vast majority of soldiers at Gettysburg and elsewhere were strangers on the land—recent arrivals to the different scenes of battle and unfamiliar with the overall landscapes in which they were fighting, except perhaps during extended sieges. In most instances they had lived hundreds of miles away, had rarely traveled, and were geographically unlearned— thus many would have been disoriented beyond their most immediate surroundings, a situation almost certainly exacerbated by the confusion of battle. And most soldiers were moved quickly out of an area and on toward other engagements. The creating, studying, and marking of a battlefield park should therefore be viewed as not only a commemorative effort, but also as an attempt to impose order on the past, on landscapes of conflict and confusion —a means of enabling veterans of a battle, students of military affairs, and the American public to comprehend the overall sweep of combat, and the strategies and tactics involved. Accurate placement of monuments, markers, and tablets required thorough historical research and mapping of a battleground, which was no easy task. The leading historian at Gettysburg was John Bachelder, an artist and illustrator who had closely studied earlier battles and arrived at Gettysburg only a few days after the fighting concluded. Bachelder's in-depth investigation of the battle area extended over a period of 31 years, until his death in 1894. In the process, he used his accumulating knowledge to prepare educational guidebooks and troop-movement maps to sell to the visiting public. In 1880, his intensive research and mapping of the battlefield benefited from a congressional appropriation of $50,000 to determine historically accurate locations of principal troop positions and movements during the battle, which encompassed extensive terrain. Similar to what would be done at other battlefields, this survey was carried on in collaboration with hundreds of veterans and other interested individuals. Their research directly influenced the positioning of monuments, markers, and tablets, and the routing of avenues for public access to the principal sites and their monuments.25 Historical accuracy was of great importance; and, not infrequently, veterans hotly disputed field research conclusions. Shiloh, for example, experienced a number of protracted, highly contentious arguments over the positioning of monuments and tablets. Two Iowa units even disagreed over what time of day they had occupied certain terrain on the battleground—the time, to be inscribed on the monuments, being a matter of status and pride to the units' veterans. This dispute lasted several years and involved appeals to the secretary of war before a settlement was finally reached. Similar disputes occurred at the other battlefield parks. At Gettysburg, the positioning of one monument was litigated all the way to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court: In 1891, the Court ruled against the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association, granting the 72nd Pennsylvania Infantry the right to place its monument in a front-line position, where its veterans insisted they should be honored for their role in confronting Pickett's Charge on the climactic day of the battle.26 Significantly, during the 1880s the South gradually became involved in commemoration at Gettysburg. As initially practiced at the battlefield, the marking and preserving of only Union positions presented a one-sided view of what took place there, confusing anyone not familiar with the shifting and complex three-day struggle and the unmarked positions of Confederate troops. The Memorial Association, firmly dedicated to commemorating the Union army's victory at Gettysburg, did little to encourage participation by former Rebels until about two decades after the battle. Four ex-Confederate officers, including General Robert E. Lee, were, however, invited to attend the 1869 Union officers' reunion at Gettysburg and advise on the location of Southern battle positions. Lee declined the invitation; and with minimal Southern involvement no sustained effort to commemorate the Southern army ensued.

Beginning in the early 1880s, what became known as Blue-Gray reunions were held on battlefields and in cities and towns around the country, bringing Union veterans into periodic social contact with their former adversaries from the South. Southern participation in the Gettysburg reunions increased considerably during this decade. At the 1888 reunion marking the 25th anniversary of the battle, both sides collaborated in a re-enactment of Pickett's Charge (one of the earliest in an amazing succession of remembrance rituals at the site of this renowned Civil War engagement). The former Confederate troops made their way in carriages across the open field toward Union veterans waiting near the stone wall and the Copse of Trees that marked the climax of the Southern charge. The cheering and handshaking when they met reflected the ongoing reconciliation between Northern and Southern veterans.27 Yet, the gathering at the Copse of Trees reflected more than just reconciliation among veterans. Across the country, attitudes in both North and South were shifting from the bitterness and hatred of war and the postwar Reconstruction period toward a reconciliation between the white populations of the two sections. The existence of slavery in the South had been a malignant, festering sore for the nation, and the most fundamentally divisive issue between the North and South as they edged toward war. Yet, as the war receded into the past, the North relented, opening the way for the end of Reconstruction and the move toward reconciliation. In so doing, white Northerners revealed a widespread (but not universal) indifference to racial concerns, and they abandoned the African American population in the South to the mercy of those who had only recently held them as slaves. This situation opened the way for intensified discrimination against, and subjugation of, recently freed black citizens of the United States. In the midst of such fateful developments, the North-South rapprochement fostered a return to the battlefields by both Union and Confederate veterans—an echo of the past, but this time for remembrance and reconciliation, not combat.28

The Blue-Gray reunions, with the co-mingling of one-time foes who were becoming increasingly cordial, moved Southerners toward the idea of battlefield preservation and development. Proud of its military exploits against the more powerful North, the former Confederacy exalted the glory, heroism, and sacrifice of its soldiers on the battlefields. Yet glory, heroism, and sacrifice were dear to Northerners as well, and this they could share with Southerners in their memories of the Civil War while avoiding the moral and ideological questions associated with slavery, the war, and postwar human rights. Thus, after considerable controversy, including angry opposition from some Northern veterans, the Gettysburg Battlefield Memorial Association approved proposals to erect two Confederate monuments of modest size: one in 1886, on Culp's Hill; and another in 1887, near the apex of Pickett's Charge—a highly significant location. These were the only Southern monuments erected on the battlefield before the end of the century, even though in 1889 the Memorial Association stated its intention to buy lands on which the Confederate army had been positioned, and to erect more monuments to mark important sites along Southern battle lines. Although it lost the battle and the war in its attempt to split the United States into two nations, the South was gradually being accepted by Northerners as worthy of honor in recognition of the heroism and sacrifice of its troops at Gettysburg. The huge 50th anniversary reunion held on the battlefield in 1913 would become a landmark of reconciliation between North and South, but the urge toward reconciliation had been clearly evident at Gettysburg three decades earlier.29 (Figure 4) The African American Role In marked contrast to the involvement of Confederate veterans, African American participation in Civil War battlefield commemoration was minimal in virtually all cases. Prior to President Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, effective January 1, 1863, some blacks served as soldiers (and sailors) for the North. But most blacks were strictly limited to their enforced roles as servants and laborers—their status being either as freedmen or contraband for the Union army, or as slaves for the Confederacy. However, the Northern success at Antietam in September 1862 spurred Lincoln to issue the Proclamation; and, beginning in 1863, blacks became increasingly active as soldiers in the Union army. It is estimated that nearly 180,000 blacks joined the United States Army before the end of the war, more than half of them recruited from the Confederate states. They served mainly in infantry, cavalry, and heavy and light artillery units. Yet African American soldiers did not fight on any of the battlefields destined to become the earliest military parks. Blacks were mustered in too late to see combat at Shiloh and Antietam in 1862, before the Proclamation. And they did not fight in the siege of the city of Vicksburg, or at Gettysburg, Chickamauga, or Chattanooga—each of which occurred in 1863. Their principal involvement was in the broader Vicksburg campaign, where they fought with distinction at the battles of Milliken's Bend and Port Hudson. (Figure 5)