|

The Upper Missouri Fur Trade Its Methods of Operation |

|

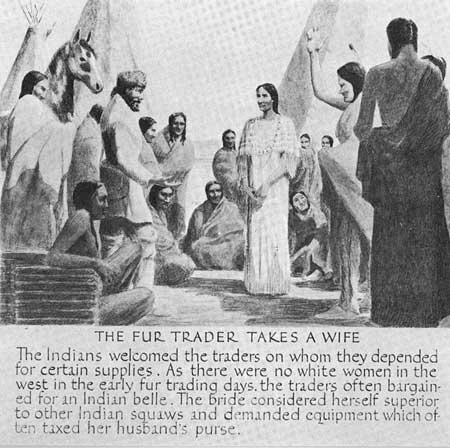

Drawing by W. Sammons, courtesy National Park Service

Although custom required the traders to be hospitable to the Indians, they ordinarily took no chances of letting the latter get out of control while the business was being conducted. At both Forts Union and McKenzie, during the early 1840's, the trade was carried on without the Indians being admitted to the interior of the posts. [33] Boller wrote that at Fort Atkinson, located near Fort Berthold, "The store is only open when the Indian wants to trade, and not more than 5 or 6 allowed in at one time, & are prevented by a high square counter from any more than passing a threshold." [34]

On the other hand, at Fort Clark, located among the comparatively peaceful Mandan, the Indians generally had free access of the establishment during the day. Maximilian wrote in 1833-1834 that at this place there was no separate apartment for them so they were in every room, and stood in front of the fireplaces during the cold winters so that they prevented the heat from coming into the apartments. They required food and smokes. The company in one winter gave an estimated 200 lbs. of tobacco to regale them. Most of them seemingly endeavored to come around the dining room at dinner time in order that they might be invited to a free meal. [35]

Although the ostensible profits from the fur trade appear to have been excessive, the real ones were not as great as they appeared. The goods traded in the 1830's for buffalo robes and beaver skins, at the place of exchange, would indicate that the trader received a profit of from 200 to 2,000 percent. Denig wrote about 1854 that "all goods are sold at an average profit of 200 percent." [36] However, the expenses involved above original cost, in carrying out this business, were immense.

Kurz wrote in 1851 that although the fur traders formerly made a "gain earlier ranging from 200 to 400 percent; their gain today is not more than 80 percent." [37] At that time the Indian received in exchange for a buffalo robe, which sold wholesale in St. Louis for at least $2.00, two gallons of shelled corn, from three to four pounds of sugar or two pounds of coffee. The price of coffee at Fort Union was $1.00 a pound; brown sugar, the same; meal 25 cents a pound; seven ship biscuits, $1.00; one pound of soap $1.00; and calico, $1.00 a yard. [38] The "agents and bourgeois," Kurz wrote "can easily realize 100 percent profit if they know the trade." [39] At that time the American Fur Company apparently did not openly trade liquor in its posts. [40]

Boller, a clerk at Fort Atkinson, in 1858, gave a similar picture of prices. "4 cups of either sugar, coffee or tea is the price of a robe, which I shall show you hereafter a few prices for it and enough. The articles just named are sold at $1 per cup! . . . We have no money currency up here; robes taking its place, for example, you want to buy a horse from an Indian—he will, if [for] a 'buffler' horse ask 30 robes for him; you will pay him in goods from the store, to the value of 30 robes, estimating each at $4, altho' the actual St. Louis cost of the goods would not be more than 30 or 40 dollars." [41]

The American Fur Company officials always contended that competition was undesirable in the business. "The Indian trade does not admit of competition," wrote Denig. "The effects of strong rival companies have been more injurious and demoralizing to the Indians than any other circumstances that have come to our knowledge, not even excepting the sale of ardent spirits among them." [42] Its methods in crushing the opposition were not unlike those of many of the large companies, such as the Standard Oil Company and others, which established monopolies and for tunes in the 19th century.

Coute que coute and ecrasez toute opposition (cost what it may and crush all opposition) seems to have been the standing order in the instructions of American Fur Company to its traders. The first step was to crush the opposition by competition. Kenneth McKenzie, bourgeois at Fort Union, explained "it is not a good policy to buy out opposition, rather work them out by extra industry and assuidity" and if "the opponents must get some robes, let it be on such terms as to leave them with no profits." [43]

If competition failed, the company then tried force. If the latter did not succeed, it would then endeavor to buy out the opposition. Many are the stories of its methods of liquidating small traders.

|

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Jan 15 2005 10:00:00 am PDT |