|

ZION

A Geologic and Geographic Sketch of Zion National Park |

|

January, 1947

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 3

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 3

A GEOLOGIC AND GEOGRAPHIC SKETCH OF ZION NATIONAL PARK

A GEOLOGIC AND GEOGRAPHIC SKETCH OF ZION NATIONAL PARK*

By HERBERT E. GREGORY

*Based on studies by the U. S. Geological Survey in cooperation with the National Parks Service. In part reproduced from descriptions on the topographic sheet of the Zion National Park (1936) and in part from "The Zion Park Region," a report in preparation. Published with the permission of the Director, U. S. Geological Survey.

GEOGRAPHIC OUTLINE

Its regional setting, its erosion pattern, and its individual features combine to give Zional National Park prominence among regions of extraordinary landscapes. Here the type of scenery peculiar to the great plateaus of Southern Utah find complete expression. The long stretches of even sky line seen on approaching the park from Cedar City (northwest), Panguitch (northeast), and Grand Canyon (southeast) give an impression of extensive flat surfaces, that terminate in lines of cliffs, but viewpoints within the park reveal a ruggedness unequalled in most mountainous regions. The canyons are so narrow, so deep, and so thickly interlaced, and the edges of the strata so continuously exposed that the region seems made up of gorges, cliffs, and mesas intimately associated with a marvelous variety of minor erosion forms. The park might be considered as a mountainous country in which departures of many thousand feet from a general surface are downward rather than upward. (See Figs. 1, 2, 3, 6.)

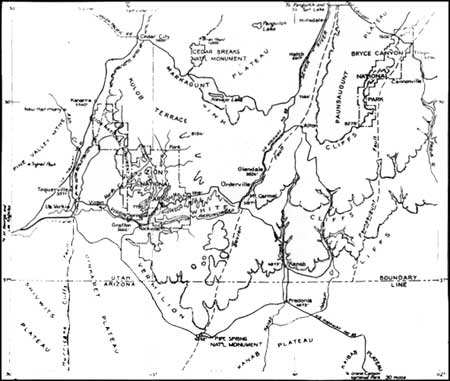

The canyons and adjoining terraces are spectacular illustrations of erosion as developed in flat-lying rocks piled high in orderly succession, but differing in hardness and durability. The tabular forms are the edges and surfaces of hard strata from which softer layers have been stripped. The vertical lines that cross them mark the position of fractures (joints)—lines of weakness which erosion enlarges into grooves and miniature canyons. In the resulting giant stairway, cliffs in resistant rocks and slopes in weak rock constitute risers and treads that vary in steepness and height with the thickness of the strata involved. Thus, near the south entrance to Zion National Park the edge of a layer of hard conglomerate (pebble stone) is a vertical cliff, and its top a wide platform. Above this platform a long slope of shales (mudstones) broken by many benches developed in hard beds, extends upward to the great cliff faces of West Temple and the Watchman. In their regional setting these huge rock steps within the park are secondary features. They have been developed on the southern flank of the Markagunt Plateau from whose broad summit at 9,000 to 11,000 feet the country descends southward in a succession of terraces, miles in width and length, separated by cliffs hundreds of feet high, to the Virgin River at Grafton, elevation 3,650 feet. (See Figs. 1 and 3.)

Figure 1. Sketch map of a part of southern Utah including Zion National

Park. The Pink Cliffs, White Cliffs. and Vermilion Cliffs are high

escarpments that mark successively lower steps cut into the south rim of

Markagunt and Paunsaugunt Plateaus. The plateaus are outlined by faults.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new

window)

The dominant feature of Zion National Park is Zion Canyon of the Virgin River, the best-known example of a deep, narrow, vertically-walled, brilliantly-colored chasm readily accessible for observation. Throughout most of its course the canyon has a flat floor one quarter mile wide and bordered by walls one half mile high. At the Narrows a streamway 20 feet wide leads between walls 2000 feet high. At the Temple of Sinawava the walls are sheer and cut from a single layer of sandstone. Farther down the canyon steep lower slopes underlie the towering walls which here and there recede into alcoves and broad amphitheaters, and everywhere are decorated by slender pilasters, broad arches, and statue-like forms. All the canyon rocks are brightly colored. The majestic vertical walls of sandstone show shades of red that gradually merge upward into white. Beneath them are mauve, purple, pink, yellow, lilac shales—the most brilliantly colored rocks known. As the colors of the canyon walls are the colors of the bare rock, not of those of rock coated with soil and masked by vegetation, the tones on sunny days differ from those on cloudy days and after rains are particularly bright.