|

ZION

A Geologic and Geographic Sketch of Zion National Park |

|

January, 1947

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 3

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 3

A GEOLOGIC AND GEOGRAPHIC SKETCH OF ZION NATIONAL PARK

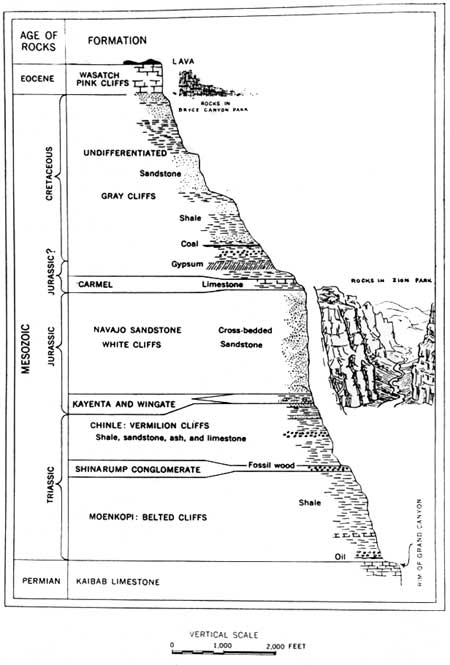

STORY OF THE ROCKS

Zion National Park is not only a region of scenic grandeur; a large part of geologic history is revealed in its canyon walls. Just as Grand Canyon is the best-known record of ancient geologic history, and Bryce Canyon reveals much of late geologic history, Zion Canyon records most clearly the events of middle (Mesozoic) geologic time. The story of Zion begins where that of Grand Canyon ends, and ends where that of Bryce begins. In the 16,000 feet of sedimentary rocks exposed in these three national parks are incorporated the records of a thousand million years. (See Fig. 7.)

A study of these rocks shows that the region including Zion National Park has witnessed many changes in landscape and climate. At times it was covered by the sea, at other times broad rivers traversed its surface, and at still other times it was swept by desert winds. Most of the rocks were laid down by water as gravel, sand, mud, and limy ooze. These have been consolidated into conglomerates, sandstones, shales, and limestones by the weight of layers above them and by the lime, silica, and iron that cemented their grains. Embedded in the rocks are fossil sea shells, fish, trees, snails, and the bones and tracks of land animals that sought their food in flood plains, in forests, or among sand dunes. The most conspicuous remains are those of dinosaurs—huge reptiles that so dominated the life of their time that the Mesozoic is known as the "age of dinosaurs."

As treated by geologists, sedimentary rocks are divided into "formations" which differ from each other in such features as mineral content, extent and thickness of individual layers, and kind of fossils. Each formation therefore reveals the geography, climate, fauna, and flora of its time. (See Fig. 7.)

Figure 7. Generalized cross section of the geologic formations exposed

in Zion Canyon and adjoining regions. (click on

image for an enlargement in a new window)

Of the six formations prominently displayed in Zion National Park, the youngest is the Carmel limestone, 200 to 300 feet thick. Isolated remnants of this widespread formation appear at the top of East Temple, West Temple, the Altar of Sacrifice, and of many mesas on Kolob Terrace. East of the park boundary all of it is prominently exposed along the Zion-Mount Carmel highway. Its fossil shells indicate the date of deposition as at least 120,000,000 years ago. Most rocks younger than the Carmel have been worn away from the park areas but immediately east and north of the park boundary they appear as about 2800 feet of gypsum, coal-bearing sandstones, and shales (Gray Cliffs) capped by 500 feet of limestone (Wasatch formation; Pink Cliffs). The youngest rocks are the lavas from volcanoes in Coalpits Wash, on Kolob Terrace, and outside the park on the summit lands of Markagunt Plateau.

Beneath the thin resistant Carmel limestone is the Navajo sandstone (White Cliffs), exceeding 2000 feet in thickness. From it have been carved the temples and towers, the cliffs and canyon walls that make Zion National Park unique among scenic regions. At the base of the cliffs of Navajo sandstone the Kayenta formation, in most places less than 200 feet thick, forms a shelving slope worn chiefly on thin maroon-colored sandstone. Beneath it is the Wingate sandstone which along the Virgin River is less than 50 feet thick and thins to extinction in Zion Canyon. On slopes leading upward to the Watchman (Fig. 6), it stands as a low cliff but generally it is inconspicuous and in mapping has been combined with the Kayenta. Below the Wingate formation and not everywhere sharply separated from it is the Chinle (Chin-lee) formation (Vermilion Cliffs). With a thickness of more than 1000 feet it forms the brightly colored slopes and low cliffs below Springdale and the uppermost beds extend up Zion Canyon nearly four miles. The Chinle rests on the Shinarump (Shin-ar-ump) conglomerate, which though less than 100 feet thick, is a prominent cliff marker. It is the cap rock of sloping walls at the mouth of the Parunuweap, and westward about Huber Wash and Coalpits Wash it forms the cape-like mesas on both sides of the Virgin River.

In turn below the Shinarump is the Moenkopi (Moen-kopi) formation (Chocolate Cliffs; Belted Cliffs), the oldest rocks exposed in Zion National Park. Along the Virgin River the whole of the Moenkopi (about 1800 feet) is displayed as a landscape of brightly colored bands. The highway through Virgin City, Grafton, and Rockville traverse successively higher beds until the top is reached at the mouth of the Parunuweap. Just outside the southwest border of the park the Kaibab limestone, the formation next older than the Moenkopi, appears in the Timpoweap canyon of the Virgin River and in Hurricane Cliffs. Extended southeastward it forms the top layer in the walls of Grand Canyon.

All the geologic formations represented in Zion National Park extend beyond its borders into the Kaiparowits and San Juan regions of southeastern Utah, the Navajo Country of northeastern Arizona, and westward into Nevada. In the park the Moenkopi, Shinarump, Chinle, Navajo, and Carmel formations are exceptionally well displayed; the Wingate and Kayenta are more fully developed elsewhere.

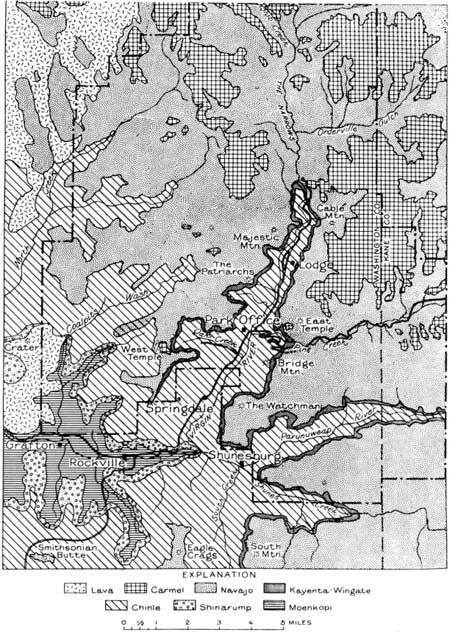

For visitors to the park who are interested in geologic history, the significant features of the formations exposed along trails and highways are outlined in the following paragraphs. (See Fig. 8.)

Figure 8. Geologic map of Zion National Park; a sketch showing the

approximate location and extent of the Triassic and Jurassic formations,

(To show their relations clearly the thicknesses of the Shinarump and

the combined Wingate and Kayenta are much exaggerated.) (click on image for an enlargement in a new

window)

As shown in figures 2, 7, and 8 the formations lie one above another in orderly succession and their edges appear along cliffs and canyon walls. The lowest (oldest) formation is exposed where the streams have cut the deepest valleys.