|

BRYCE CANYON

A Geologic and Geographic Sketch of Bryce Canyon National Park |

|

June, 1941

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 4

Zion-Bryce Museum Bulletin

Number 4

A GEOLOGIC AND GEOGRAPHIC SKETCH OF BRYCE CANYON NATIONAL PARK

By HERBERT E. GREGORY

* Based on studies by the U. S. Geological Survey in cooperation with the National Park Service. In part reproduced from the Kaiparowits Region by Gregory and Moore; in part from descriptions on the topographic sheet of the Bryce Canyon National Park (1939) and in part from "The Bryce Canyon National Park Region" a report in preparation. Published with the permission of the Director, U. S. Geological Survey.

GEOGRAPHIC OUTLINE

As a geographic unit, Bryce Canyon National Park is a choice portion of the plateau lands of the Colorado drainage basin, 50,000 square miles of rock tables, cliffs, and canyons that seem to have an unlimited range in color, form, and size.

Of this vast region of unexcelled scenery in Utah and Arizona, Bryce Canyon National Park is but a short, narrow strip along the southeastern rim of the Paunsaugunt Plateau, and this plateau is only one of the seven great tables that dominate the landscape of southern Utah. In such a setting, the region that includes the park might have attracted little attention were it not that within its borders are features of exceptional interest, some of them unique; and the surroundings are truly magnificent.

In broad outline, the history of the park is the history of the Paunsaugunt Plateau—a fascinating story of geological events that needs no profound study for interpretation. Few. if any, places in the world afford better opportunity to realize the power and persistence of the forces that have shaped the surface of the earth, for though displayed on an enormous scale, the rock units show a certain simplicity of mass composition, form, and arrangement that makes their relations clear.

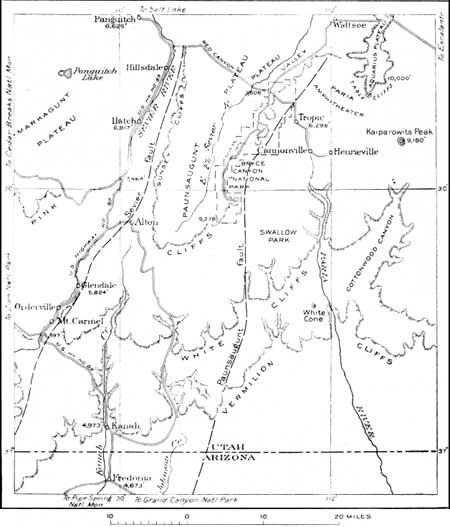

On the approach roads to the park from Grand Canyon and Zion Canyon through Hatch (south and west) and from central Utah through Panguitch (northwest), (See Fig. 1.) visitors are confronted by the great pink wall of Sunset Cliffs along the Sevier River, easily recognizable as a single group of strata in plain sight for 30 miles. As the road leads eastward, the gorgeously colored Red Canyon explains itself—a ready-made gap in these cliffs that afford passage from their base to their top. Likewise, little knowledge of geology is required to recognize the flat land between Red Canyon and the entrance to Bryce Canyon National Park as the eastward extension of the pink beds of Sunset Cliffs, here weathered to buff and gray; or that the glorious pink wall within the park is but the eastern edge of the broad table of which Sunset Cliffs is the western edge, or that Bryce Canyon is but a niche in a long, high, painted wall—a brilliant jewel in a land of superb texture and workmanship.

Figure 1. Sketch map of a part of Southern Utah including Bryce Canyon

National Park. The Pink Cliffs, White Cliffs, and Vermilion Cliffs are

high escarpments that mark successively lower steps cut into the south

rim of Markagunt, Paunsaugunt, and Aquarius Plateaus. The Plateaus are

outlined by faults. (click on image for an

enlargement in a new window)

The long stretches of even sky line seen on approaching the park give an impression of extensive flat surfaces that terminate in lines of cliffs, but view-points within the park reveal a ruggedness possessed by few other regions. The canyons are so narrow, so deep, and so thickly interlaced, and the edges of the strata so continuously exposed that the region seems made up of gorges, cliffs, and mesas intimately associated with a marvelous variety of minor erosion forms. These features are developed on a scale that in other regions would justify the term mountainous.

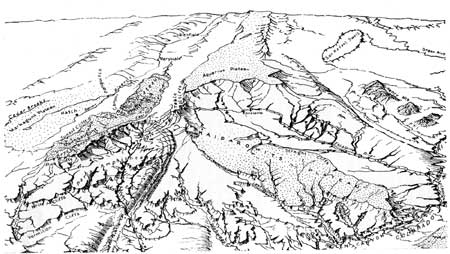

The canyons and adjoining terraces are spectacular illustrations of erosion. They show with diagrammatic clearness the work of running water, rain, frost, and wind, of ground water and chemical agencies active throughout a long period of time. The horizontal tables and benches, broken by vertical lines that in distant view appear to dominate the landscape, are normal features of erosion of plateau lands in an arid climate. The tabular forms are the edges and surfaces of hard strata from which softer layers have been stripped. The vertical lines mark the position of fractures (joints)—lines of weakness which erosion enlarges into grooves and miniature canyons. As they entrench themselves in horizontal layers of rock that vary in resistance to erosion, the master streams and their tributaries are developing stairlike profiles on their enclosing walls. Cliffs in resistant rocks, and slopes in weak rock constitute risers and treads that vary in steepness and height with the thickness of the strata involved. These characteristic erosional features of Bryce Canyon National Park derive an added meaning from the contemplation of the surrounding region. The park is famous not only for the scenery within its borders but also for the marvelous views from the lofty rim of the Paunsaugunt Plateau that overlooks the spectacular landscapes of southern Utah. (See Fig. 2, 3)

Figure 2. Generalized sketch of the plateaus, mountains, cliffs, and

canyons of south central Utah showing the topographic setting of Bryce

Canyon National Park. From Bryce Point the air-line distance to the

Henry Mountains is approximately 80 miles, to Navajo Mountain 85 miles,

to the mouth of the Paria River 60 miles, and to Cedar Breaks 50 miles.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new

window)

At its eastern border the generally flat Paunsaugunt Plateau gives way to a region of extreme ruggedness, difficult to penetrate. In Dutton's picturesque language, "to cross such regions except in specified ways is a feat reserved for creatures endowed with wings." Beginning abruptly at Sunset Point, newly made meandering trails lead steeply downward along trenches between serrated walls to the floor of Paria Valley, 2,000 feet below. Beyond this flat floor appear interlocking ridges, trenched by narrow, deep canyons, in places more than 20 of them in a mile, that carry water to the Paria or directly to the Colorado. Along this course the rim of the lofty Kaiparowits Plateau, cut by innumerable notches at the heads of innumerable canyons, stands on the sky line and carries the view southeastward to the dome of Navajo Mountain beyond Glen Canyon 80 miles away. From Sunset Point northeastward, the details of the amazing landscape are dwarfed by the towering plateau headlands that stand 2,000 feet above the rim of the Paunsaugunt Plateau and 4,000 feet above the Paria. A pack train traverse along the base of Kaiparowits Plateau in and out of canyons, through narrow defiles, across sharp ridges and flat-topped mesas to the edge of Glen Canyon at the "Crossing of the Fathers" is a memorable experience, or those fortunate enough to ascend Table Cliffs and follow its flat surface to Powell Monument will find spread out before them a landscape matched in scope and beauty only at view points on Navajo Mountain. It is an unparalled scene of gorges, plateaus, of mesa walls and volcanic piles on both sides of the Colorado canyons, and on a scale so vast as to obscure erosional features that in other regions would dominate the landscape. (See Fig. 3)

Figure 3. View from the rim at Inspiration Point across lower portion of

Bryce Canyon and across upper Paria River Valley (Paria Amphitheater).

Table Cliffs in the left distance. Village of Tropic, Utah in right

center. (N. P. S. photo by Grant)

The rim road in Bryce Canyon National Park is on the highest tread of a gigantic rock stairway cut in the flank of the great plateau. As viewed at Rainbow Point, the country descends southward in an orderly succession of terraces miles in width, separated by cliffs hundreds of feet high, across the White Cliffs and the Vermilion Cliffs to the Kanab Plateau 60 miles distant and 4,000 feet below. The terraces are trenched by deep gorges, and from their floors rise small mesas and towers and such high mesas as the conspicuous White Cone.

In this broad landscape, flowing water is conspicuously absent. The one lake in view is the lone representative of its class in many square miles of territory.

In this region the gentle slopes and sweeping curves that make up the artist's "line of beauty" are lacking. They are replaced by horizontal lines, vertical lines, and oblique lines that meet at angles, and along their trends are offset many times. The rounded hills, the gently inclined valley sides, the flat river bottoms of other regions are replaced by flat tables, vertical walls, and lowlands cut into angular forms that differ from their larger companions only in size. Because of the absence of soil and covering vegetation, the walls and canyon floors are the color of bare rock; the blue of distant highlands, and the subdued tones of "hillside and lowland meadows" in more humid regions are likewise lacking. The landscape of all southern Utah is banded with distant colors—dominantly shades of red, yellow, and brown—that in few places merge into a composite tone. Areas of green or of gray are rare.