|

FORT SUMTER National Monument |

|

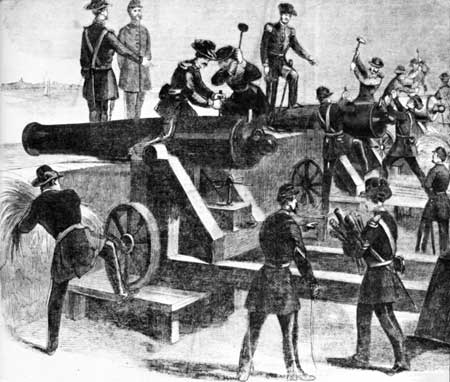

Spiking the guns at Fort Moultrie, just prior to

departure for Fort Sumter, December 26, 1860.

From Frank

Leslie's Illustrate Newspaper, January 5, 1861.

Major Anderson

Moves Garrison from Moultrie to Sumter

On December 20, 1860, South Carolina seceded from the Union. On the night of the 26th, fearing attack by the excited populace, Maj. Robert Anderson removed the small garrison he commanded at Fort Moultrie to Fort Sumter out in the harbor. Ignorant of an apparent pledge to maintain the harbor status quo, given by President Buchanan some weeks before, Anderson moved in accordance with instructions received December 11, which read:

. . . you are to hold possession of the forts in this harbor, and if attacked you are to defend yourself to the last extremity. The smallness of your force will not permit you, perhaps, to occupy more than one of the three forts, but an attack on or attempt to take possession of any one of them will be regarded as an act of hostility, and you may then put your command into either of them which you may deem most proper to increase its power of resistance. You are also authorized to take similar steps whenever you have tangible evidence of a design to proceed to a hostile act."

Anderson thought he had "tangible evidence" of hostile intent, both towards Fort Moultrie—an old fort most vulnerable to land attack—and towards unoccupied Fort Sumter. He moved now "to prevent the effusion of blood" and because he was certain "that if attacked my men must have been sacrificed, and the command of the harbor lost." To Anderson, a Kentuckian married to a Georgia girl, preservation of peace was of paramount importance. At the same time, a veteran soldier of "unquestioned loyalty," he had a duty to perform.

Charleston was filled with excitement and rage. Crowds collected in the streets; military organizations paraded; and "loud and violent were the expressions of feeling against Major Anderson and his action."

There was almost as much consternation in Washington as in Charleston. Senators calling at the White House found President Buchanan greatly agitated. He stood by the mantelpiece, crushing a cigar in the palm of one hand, and stammered that the move was against his policy. The cabinet was called into session, and on December 27, Secretary of War Floyd wired Major Anderson:

"Intelligence has reached here this morning that you have abandoned Fort Moultrie, . . . and gone to Fort Sumter. It is not believed, because there is no order for any such movement. Explain the meaning of this report."

Maj. Robert Anderson.

From Lossing,

A History of the Civil War.

South Carolina regarded Anderson's move not only as an "outrageous breach of faith," but as an act of aggression, and demanded, through commissioners, that the United States Government evacuate Charleston Harbor. President Buchanan, anxious to conciliate as well as maintain authority, wavered. Cabinet pressures were brought to bear. Meanwhile, on the 27th, South Carolina volunteers seized Castle Pinckney and Fort Moultrie. On the 28th, the President refused to accede to South Carolina's demand.

The North was exultant, Amid cheers for Major Anderson, salvos of artillery resounded in northern cities on New Year's Day, 1861. By an imposing majority, the House of Representatives voted approval of Major Anderson's "bold and patriotic" act.

At Fort Sumter, Major Anderson had two companies of the First United States Artillery—about 85 officers and men in a fortification intended for as many as 650. He had only "about 4 months" supply of provisions for his command. The question of reenforcement and supply was to trouble all the remaining days of the Buchanan administration and to carry over to the succeeding administration. In it were the seeds of war.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |