|

FORT SUMTER National Monument |

|

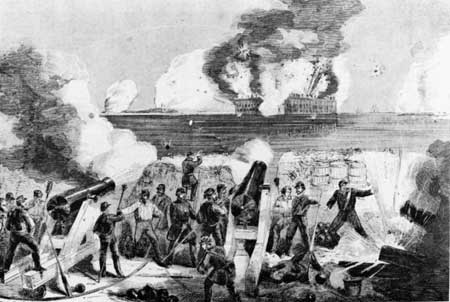

Artist's conception of the bombardment of Fort Sumter, April

12, 1861. Fort Johnson is in the foreground.

From Harper's

Weekly, April 27, 1861.

The War

Begins—April 12, 1861

"I count four by St. Michael's chimes, and I begin to hope. At half past four, the heavy booming of a cannon! I sprang out of bed and on my knees, prostrate, I prayed as I never prayed before."

At 4:30 a. m., a mortar at Fort Johnson fired a shell which arched across the sky and burst almost directly over Fort Sumter. This was the signal for opening the bombardment. Within a few minutes, a ring of guns and mortars about the harbor—43 in all—were firing at Sumter.

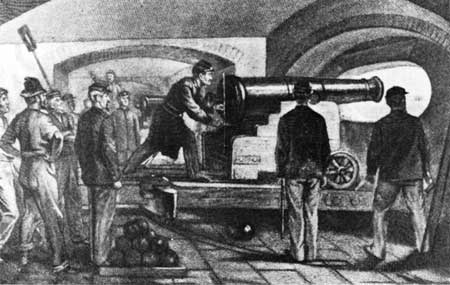

Preparing to fire the first shot from Fort Sumter, April 12,

1861. Contemporary artist's conception.

Courtesy Charleston Library Society.

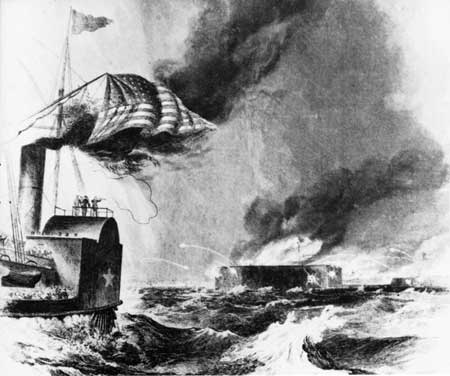

The bombardment of Fort Sumter, April 13, 1861.

Major Anderson withheld fire until about 7 o'clock. Then Capt. Abner Doubleday, of latter-day baseball fame, fired a shot at the Ironclad Battery on Cummings Point. Ominously, the light shot "bounded off from the sloping roof . . . without producing any apparent effect." Not at any time during the battle did the guns of Fort Sumter do great damage to the Confederate defenses. Most of Fort Sumter's heaviest guns were on the parapet and in the parade, and, to reduce casualties in the small garrison, Major Anderson ordered these left unmanned. For a while, with the help of the 43 engineer workmen remaining at the fort, 9 or 10 of the casemate guns were manned. But by noon, the expenditure of ammunition was so much more rapid than the manufacture of new cartridge bags that the firing was restricted to 6 guns only. Meanwhile

"Showers of balls from 10-inch Columbiads and 42 pounders, and shells from [10] inch mortars poured into the fort in one incessant stream, causing great flakes of masonry to fall in all directions. When the immense mortar shells, after sailing high in the air, came down in a vertical direction, and buried themselves in the parade ground, their explosion shook the fort like an earthquake."

All Charleston watched. Business was entirely suspended. King Street was deserted. The Battery, the wharves and shipping, and "every steeple and cupalo in the city" were crowded with anxious spectators. And "never before had such crowds of ladies without attendants" visited the streets of Charleston. "The women were wild" on the housetops. In the darkness before dawn there were "Prayers from the women and imprecations from the men; and then a shell would light up the scene." As the day advanced, the city became rife with rumors: "Tonight, they say, the forces are to attempt to land. The Harriet Lane had her wheel house smashed and put back to sea. . . . We hear nothing, can listen to nothing. Boom boom goes the cannon all the time. The nervous strain is awful. . . ." Volunteers rushed to join their companies. There was "Stark Means marching under the piazza at the head of his regiment . . . ," his proud mother leaning over the balcony rail "looking with tearful eyes." Two members of the Palmetto Guards paid $50 for a boat to carry them to Morris Island.

The barracks at Fort Sumter caught fire three times that first day, but each time the fire was extinguished. One gun on the parapet was dismounted; another damaged. The wall about one embrasure was shattered to a depth of 20 inches. That was the Blakely rifle, in part, firing with "the accuracy of a duelling pistol." The quarters on the gorge were completely riddled. When night descended, dark and stormy, Fort Sumter's fire ceased entirely. With the six needles available, the work of making cartridge bags went forward; blankets, old clothing, extra hospital sheets, and even paper, were used in the emergency. In the meantime, the supply fleet, off the bar since the onset of hostilities, did no more than maintain its position. It had been crippled upon departure when Seward's meddling had caused withdrawal of the powerful warship Powhatan. Now, bad weather prevented even a minimum supporting operation.

Interior of Fort Sumter after the bombardment of April 1861. The

Left Flank barrack is at the left; the Left Face is at the right.

From G. S. Crawford, The Genesis of the Civil War.

Interior of the Gorge after the April 1861 bombardment. Parade

entrance to sally port is at center.

On the morning of the 13th, Sumter opened "early and spitefully," and, with the increased supply of cartridges, for a while kept up a brisk fire. About midmorning hot shot set fire to the officers' quarters. The Confederate fire then increased; soon the whole extent of the quarters was in flames; the powder magazines were in danger. The blaze spread to the barracks. By noon the fort was almost uninhabitable. The men crowded to the embrasures for air or lay on the ground with handkerchiefs over their mouths. For a time the fort continued to fire; valiant efforts had saved some of the powder before the onrush of the flames forced the closing of the magazines. Meanwhile, at every shot, the Confederate troops, "carried away by their natural generous impulses," mounted the different batteries and "cheered the garrison for its pluck and gallantry and hooted the fleet lying inactive just outside the bar."

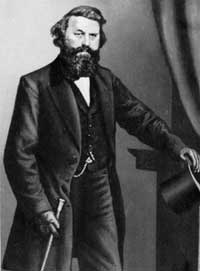

Col. Louis T. Wigfall. From Mrs. D. Giraud Wright, A Southern Girl in '61. Courtesy Doubleday & Company. |

About 1:30 in the afternoon the flag was shot down. Almost accidentally, this led to surrender. By authority of General Simons, commanding on Morris Island, Col. Louis T. Wigfall, one of General Beauregard's aides detached for duty at that spot, set out by small boat to ascertain whether Major Anderson would capitulate. Till recently, Wigfall had been United States Senator from Texas. Before he arrived at the beleaguered fort, the United States flag was again flying, but Wigfall continued on. The firing continued from the batteries across the harbor. Once through an embrasure on the Left Flank, white handkerchief on the point of his sword, Colonel Wigfall offered the Federal commander any terms he desired, only "the precise nature of which" would have to be arranged with General Beauregard. Anderson accepted on the basis of Beauregard's original terms: evacuation with his command, taking arms and all private and company property, saluting the United States flag as it was lowered, and being conveyed, if desired, to a Northern port. The white flag went up again; the firing ceased. Wigfall departed confident that Anderson had surrendered unconditionally. He and his boatman were borne ashore "in triumph."

Meanwhile, officers had arrived at the fort direct from General Beauregard's headquarters in Charleston. From these men, dispatched to offer assistance to the Federal commander, Anderson learned that Wigfall's action was unauthorized; that, indeed, the colonel had not seen the Commanding General since the start of the battle. From another party of officers he learned Beauregard's exact terms of surrender. They failed to include the privilege of saluting the flag, though in all other respects they were the same as those Anderson believed he had accepted from Wigfall. Impetuously, Anderson had first declared he would run up his flag again. Then, restrained by Beauregard's aides, he waited while his request for permission to salute the flag was conveyed to the Commanding General. In the course of the afternoon, General Beauregard courteously sent over a fire engine from the city. About 7:30 that evening, Beauregard's chief of staff returned with word that Major Anderson's request would be granted and the terms offered on the 11th would be faithfully adhered to. The engagement was officially at an end. During the 34-hour bombardment, more than 3,000 shells had been hurled at the fort.

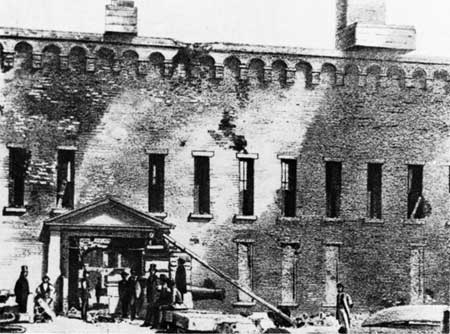

Exterior of the Gorge after the April 1861

bombardment. The sally port is at the left.

On Sunday, April 14, Major Anderson and his garrison matched out of the fort with drums beating and colors flying and boarded ship to join the Federal fleet off the bar. On the 50th round of what was to have been a 100-gun salute to the United States flag, there occurred the only fatality of the engagement. The premature discharge of a gun and the explosion of a pile of cartridges resulted in the death of Pvt. Daniel Hough. Another man, mortally wounded, died several days later. The 50th round was the last. Now, as the steamer Isabel went down the channel, the soldiers of the Confederate batteries on Cummings Point lined the beach, silent, heads uncovered.

The following day, April 15, 1861, Abraham Lincoln issued a call for 75,000 militia. Civil war, so long dreaded, had begun. The States of Virginia, Arkansas, Tennessee, and North Carolina now joined the Confederacy.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |