|

FORT SUMTER National Monument |

|

The first great breech in Fort Sumter's walls. Left Face interior,

August 20, 1863. From an original photograph by G. S. Cook.

Courtesy Mrs. T. R. Simmons, Charleston.

The First Great

Bombardment of Fort Sumter

After some experimental firing starting August 12, the bombardment of Fort Sumter began in earnest on August 17. Nearly 1,000 shells were hurled at the fort that first day; nearly 5,000 more during the week following. Even at the end of the first day it was obvious that Fort Sumter was never intended to withstand "200 pound Yankee Parrotts." Then, 3 days later, a 13-ton monster throwing 250-pound shells was added, making 18 rifled cannon in action. Because of the range involved, the fort could not reply to the land batteries, and the monitors presented themselves only fleetingly.

On the 21st, with the "Swamp Angel" in position, Gillmore demanded the evacuation of Fort Sumter and Morris Island, threatening direct fire on the city of Charleston. Gillmore's ultimatum was unsigned, and General Beauregard was absent from his headquarters; but before confirmation could be secured, Gillmore had opened fire on the city. But little damage had been done when, on the 36th round, the "Swamp Angel" burst. Meanwhile, Beauregard had delivered an indignant reply. The bombardment of Fort Sumter continued.

By the 24th, General Gillmore was able to report the "practical demolition" of the fort. On that date, only one gun remained "serviceable in action." On the morning of the 23d, against Dahlgren's ironclads, Fort Sumter had fired what were to be its last shots in action. Its brick masonry walls were shattered and undermined; a breach 8 by 10 feet yawned in the upper casemates of the left face; at points, the sloped debris of the walls already provided a practicable route for assault.

Still, the Confederate garrison, supplemented by a force of 200 to 400 Negroes, labored night and day, strengthening and repairing. The debris, accumulating above the sand-and cotton-filled rooms, itself bolstered the crumbling walls. On August 26, General Beauregard ordered Fort Sumter held "to the last extremity."

The bombardment continued sporadically during the week following. On the night of September 1—2, the ironclads moved against the fort—the first major naval operation against Fort Sumter since the preceding April. Attempts earlier in the week had been thwarted by circumstance; now, conditions were right. For 5 hours, the frigate New Ironsides and five monitors bombarded the fort, now without a gun with which to reply to the "sneaking sea-devils." Two hundred and forty-five shot and shell were hurled against the ruin—twice as many as were thrown in the April attack. Then, tidal conditions, as much as a "rapid and sustained" fire from Fort Moultrie, forced the monitors' withdrawal.

Shell from the monitor Weehawken exploding

on the interior of Fort Sumter, September 8, 1863.

From

an original photograph by G. S. Cook, Courtesy Charleston Chapter No. 4,

United Daughters of the Confederacy.

Some desultory firing on the 2d brought to a close the first sustained bombardment of Fort Sumter. Over 7,300 rounds had been hurled against the fort since the opening of fire on August 17. With the fort, to all intents, reduced to a "shapeless and harmless mass of ruins," the Federal commanders now concentrated on Battery Wagner, to which General Gillmore's sappers had come within 100 yards.

On the morning of September 5, Federal cannoneers commenced a devastating barrage against that work. For 42 hours, night and day, in a spectacle "of surpassing sublimity and grandeur," 17 mortars and 9 rifled cannon, as well as the powerful guns of the ironclads, pounded the earthwork. Calcium lights "turned night into day." On the night of September 6—7, the Confederate garrisons at Wagner and Gregg evacuated; Morris Island, after 58 days, was at last in the hands of Union troops. Just three-quarters of a mile away stood Fort Sumter.

Maj. Stephen Elliott.

From Johnson, The

Defense of Charleston Harbor.

Sumter remained defiant. When Admiral Dahlgren demanded the fort's surrender, on the morning of the 7th, General Beauregard sent word that the admiral could have it when he could "take it and hold it." On September 4 the garrison had been relieved with fresh troops—320 strong. Maj. Stephen Elliott succeeded to the command.

Admiral Dahlgren "immediately designed to put into operation a plan to capture Fort Sumter." As a preliminary, the monitor Weehawken was ordered to pass in around Cummings Point "to cut off all communication by that direction." Later in the day, the New Ironsides and the remaining ironclads were to move up "to feel, and if possible, pass" the obstructions believed to be in the channel north of Sumter. But the Weehawken grounded, and the monitors caught such a severe fire from Fort Moultrie and the other Confederate batteries on Sullivan's Island, that Admiral Dahlgren "deemed it best to give [his] entire attention to the Weehawken" and withdraw. Whatever his original plan, Admiral Dahlgren now determined upon a small-boat assault. The task seemed simple; there was "nothing but a corporal's guard in the fort ... all we have to do is go and take possession."

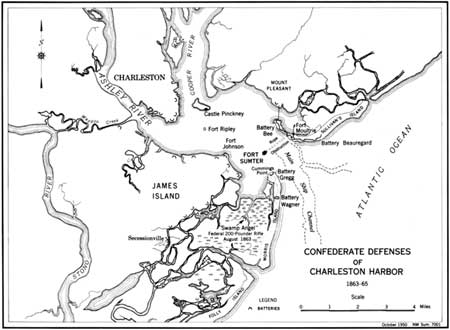

Confederate Defenses of Charleston Harbor.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |