|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The Strategic Importance of Petersburg

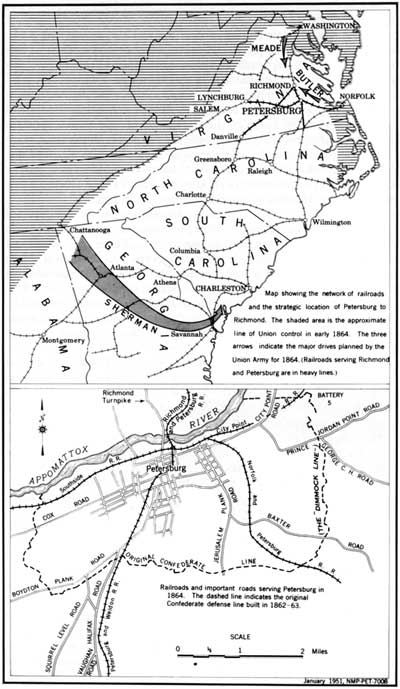

According to the United States census of 1860, Petersburg was a city of 18,266 people. It was situated on the southern bank of the Appomattox River less than 8 miles from City Point, the place where the Appomattox joins the James; 23 miles north was Richmond. As the war progressed and the territory to the north and east was shut off, Richmond became increasingly dependent on Petersburg for supplies. Through it passed a constant stream of war materials and necessities of life from the South to sustain the straining war effort. In short, Petersburg was a road and rail center of considerable importance to the Confederacy.

The transportation vehicles of that day did not require the wide, straight highways of the present. However, several good roads came into the city from the east, south, and west where they effected a junction with the Richmond Turnpike. Along these roads passed supply wagons, couriers, and, on occasion, troops on their way to repel the foe. Several were built of logs laid across the road to form a hard surface. Because of this they were called "plank roads." Thus two of the most important arteries of traffic into Petersburg were the Jerusalem Plank Road, connecting Petersburg with Jerusalem (now Courtland), Va., and the Boydton Plank Road which led south through Dinwiddie Court House. Among others of importance were the City Point, Prince George Court House, Baxter, Halifax, Squirrel Level, and Cox Roads.

It was the railroads, more than the highways, however, which imparted a significance to Petersburg out of all proportion to its size. Confederate leaders were painfully aware that loss of control over their small and harassed network of railroads would mean the loss of the war. Since Petersburg was a point of convergence for five lines, it was of great importance to the South. As other lines of supply were cut off or threatened, the dependence of Richmond upon Petersburg increased. By June 1864 all but one railroad from the south into the Confederate capital—the Richmond and Danville Railroad—passed through Petersburg.

Tracks radiated from Petersburg in all directions. The Richmond and Petersburg Railroad left the city to the north. The Southside Railroad ran west to Lynchburg, while the Petersburg and Weldon Railroad led south to North Carolina. The Norfolk and Petersburg Railroad passed through a ravine east of the city before turning southeast in the direction of Norfolk. For good measure the Petersburg and City Point Railroad struck out for the hamlet of City Point, situated at the junction of the James and Appomattox Rivers 8 miles away. Because of its proximity, Petersburg was a part of the transportation system of the Confederate capital. It served as a major point of transfer to the larger metropolis for products and materials from the vast region to the south.

In the spring of 1862, McClellan had threatened Richmond from the east and southeast. This "Peninsular Campaign" made the defenders of Richmond acutely aware of the need for a system of fortifications around Petersburg. In August of that same year a defense line was begun, and work continued until its completion about a year later. Capt. Charles H. Dimmock was in charge of it under the direction of the Engineer Bureau, Confederate States Army, and the line so constructed became unofficially known as the "Dimmock Line."

Gen. P. G. T Beauregard, who held the Confederate defense line before Petersburg until Lee arrived. Courtesy, National Archives. |

When finished, the chain of breastworks and artillery emplacements around Petersburg was 10 miles long. It began and ended on the Appomattox River and protected all but the northern approaches to the city. The 55 artillery batteries were consecutively numbered from east to west. Although natural terrain features were utilized whenever possible, some glaring weaknesses existed. For example, between Batteries 7 and 8 lay a deep ravine which could provide a means of penetration by an attacking force. The very length and size of the fortifications proved to be a disadvantage. It meant that a larger number of troops would be necessary to defend the line than General Beauregard, charged with this heavy responsibility, had present for duty. Col. Alfred Roman, an aide de-camp of Beauregard, estimated that the long "Dimmock Line" would take more than 10 times as many men to defend as were available.

The first serious threat to the untested line occurred when the Army of the James was dispatched to approach Richmond from the southeast by way of the James River. Although, the Army of the James was soon neutralized by being bottled up in Bermuda Hundred by a smaller Confederate force, it would be wrong to assume that the Union force was completely out of the picture. It not only immobilized a considerable number of Confederate soldiers assigned to guard it, but it provided a reservoir of troops for operations in other parts of the field. On several occasions raids were made on the railroads south and west of Petersburg. The most serious of these occurred on June 9, 1864, when 3,000 infantry and 1,300 cavalry appeared in force along the eastern sector of the Dimmock Line. The infantry contented itself with a menacing demonstration, but the cavalry attacked on the Jerusalem Plank Road. It was halted by the joint efforts of regular Southern Army units assisted by a hastily summoned home guard of old men and youths. The damage done by raids such as this was quickly patched up, but they were a constant nuisance to the city's transportation lines. To shut off permanently the supplies that streamed along the railroads, the Union commanders realized that it would be necessary to take permanent physical possession of them.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |