|

PETERSBURG National Battlefield |

|

The wharves and supply vessels at City Point,

Va., Union headquarters and supply base on the James River.

Courtesy, National Archives.

Union Encirclement Continues

The relentless westerly advance of the besieging force was soon resumed after the capture of the Weldon Railroad in August. Constant skirmishing occurred between the lines until, in late September, Grant struck again.

The Battle of Peebles' Farm, September 29 to October 1, was really the second section of a two-part struggle. The first took place closer to Richmond and was directed at Fort Harrison, a strongly fortified point on the outer defense line of the capital. Fort Harrison was located a mile north of the James River and approximately midway between Richmond and Petersburg. On the morning of September 29, Union troops advanced and captured the fort and held it the next day against a counterattack by the late occupants. At the same time Meade was moving toward a further encirclement of Petersburg with about 16,000 troops. The direction of his attack was northwest toward Confederate earthworks along the Squirrel Level Road. The ultimate goal was the capture of the Southside Railroad.

Fighting began on the 29th as the Blue vanguard approached the Confederates in the vicinity of Peebles' Farm. The engagement increased in fury on the 30th and continued into the 1st day of October. When the smoke of battle had blown away on October 2, Meade had extended the Union left flank 3 miles farther west and had secured the ground on which Fort Fisher would soon be built. This fort was to be the Union's biggest and was one of the largest earthen forts in Civil War history. He had, however, stopped short of the coveted Southside Railroad. Against the gain in territory the Union Army had suffered a loss of over 1,500 prisoners to the Confederacy and more than 1,000 in killed and wounded. The Southerners found that their lines, while unbroken, were again extended. Each extension meant a thinner Confederate defense line.

"The Dictator" or "The Petersburg Express," a

13-inch, 17,000-pound mortar which the Union Army used to shell

Petersburg from a distance of two and one-half miles.

Courtesy,

National Archives.

For a period of a little over 3 weeks after the Battle of Peebles' Farm the shovel and pick again replaced the musket as the principal tools for soldiers on both sides. Forts were built, breastworks dug, and gabions constructed. Then, on October 27, the Union troops moved again. This time they turned toward Boydton Plank Road and a stream known as Hatcher's Run, 12 miles southwest of Petersburg.

The general plan of operations was nearly the same as that used at Peebles' Farm. Butler's Army of the James was ordered to threaten attack in front of Richmond. Meanwhile, at the left of the Union line 17,000 infantry and cavalry of the Army of the Potomac started for the Boydton Plank Road. They made rapid progress, driving the enemy outposts ahead of them and advancing in two long columns until they reached the vicinity of Burgess' Mill where the Boydton Plank Road crossed Hatcher's Run.

It was in the neighborhood of Burgess' Mill that heavy Confederate opposition was met. Here a spirited engagement took place between the two contending forces. A failure of Union Generals Hancock of the II Corps and Warren of the V Corps to coordinate the efforts of their respective columns, coupled with stout Confederate infantry resistance and a dashing charge by Hampton's cavalry in a manner reminiscent of "Jeb" Stuart, resulted in a speedy Northern withdrawal. The Boydton Plank Road, for a time at least, remained in Southern hands, and Grant's encircling movement had received a temporary check.

The approach of winter made any large-scale effort by either side less probable, although daily skirmishes and tightening of the siege lines continued. The slackening of hostile action was used to good advantage by Union and Confederate alike, as it had been in the previous respires between battles, in the strengthening of the battle lines and efforts to develop some rudimentary comforts in the cheerless camps. Throughout the last 2 months of 1864 and the first month of the new year there were no strong efforts by either side before Petersburg; picket duty, sniping, and patrolling prevailed. Lee now had a 35-mile front, with the left resting on the Williamsburg Road east of Richmond and the right on Hatcher's Run southwest of Petersburg. To hold this long line he had but 57,402 effective soldiers on December 31. Facing these undernourished and ragged soldiers, there were, according to official returns of the same date, 110,364 well-fed and equipped Union troops.

The picture throughout the rest of the South was no more reassuring to the Confederate sympathizers. In the Shenandoah Valley of Virginia, northwest of Richmond, Gen. Philip H. Sheridan had crushed the Southern forces of Gen. Jubal A. Early at Cedar Creek on October 19 and was destroying the scattered resistance that remained. Far to the south Gen. William T. Sherman had captured Atlanta, Ga., in September 1864, and Savannah had surrendered on December 21. As the new year dawned his army was prepared to march north toward Grant. To complete the gloomy Southern prospects, Fort Fisher, bastion of Wilmington, N. C., which was the last of the great Atlantic Coast ports to remain in their possession, was under fatal bombardment by mid-January.

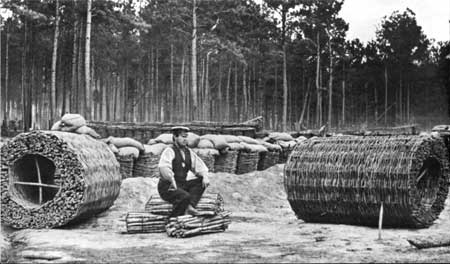

A section of the Union siege line around

Petersburg. Note the use of wickerware (gabions), sharpened stakes

(fraises), and branches (abatis) to protect the lines.

Courtesy,

National Archives.

Making sap rollers, Union line.

Courtesy, National Archives.

Deserted huts on the Confederate line in 1865.

Courtesy, National Archives.

The Battle of Hatcher's Run, February 5 to 7, 1865, was the result of a further drive by the Northern forces in their attempt to encircle Petersburg. The two Union Corps (the II and the V), which had been stopped at Burgess' Mill, again marched toward Hatcher's Run. As before, their objective was the Boydton Plank Road. This time they reached their goal with little trouble on February 5.

Union battery of Parrott guns before

Petersburg.

Courtesy, National Archives.

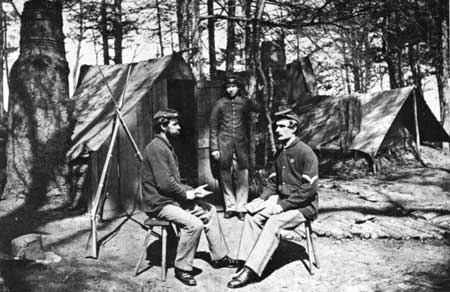

Camp scene on the Union line. Behind the seated

soldiers are good examples of the type of improvised quarters built by

many of the troops.

Courtesy, National Archives.

Confederate opposition to this advance lasted through 3 days, but it was ineffective. This was due to several factors: the inferior numbers of the Southern Army, the extremely bad weather which made a Union attack appear unlikely, the ravages of cold on badly equipped and uniformed men, and, most important, the breakdown of the food supply system.

After having been successful in capturing the Boydton Plank Road and beating off Confederate attacks, the Northern leaders decided that the road was not worth holding. It was not as important an artery of traffic as they had supposed. Consequently, they made no attempt to hold it, but they did occupy and fortify the newly extended line to Hatcher's Run at a point 3 miles below Burgess' Mill. Thus, again the Union lines had been pushed to the west, and, as before, Lee was forced to lengthen his defenses. The Petersburg-Richmond front with its recent extension now stretched over 37 miles, and the army holding it had dwindled through casualties and desertion to a little more than 46,000 in number on March 1, 1865.

The Battle of Hatcher's Run was another fight in the constant movement of the Union Army to the west after June 18, 1864. In its relentless extension around Petersburg, which continued day by day with the addition of a few more feet or yards of picket line and rifle pits, there had occurred five important thrusts aimed by the Northern leaders at encircling Petersburg. They included two attacks on the Weldon Railroad, in June and August 1864; Peebles' Farm, in September and October; Burgess' Mill, in October; and, finally, the move on the Boydton Plank Road in February 1865. They met with varying degrees of success, but still the Union noose was not drawn tightly enough.

The enlisted men of both armies, however, remained largely unaware of the strategy of their commanders. Their daily existence during the campaign took on a marked flavor, different in many respects from the more dashing engagements which preceded it. Too often war is a combination of bloodshed and boredom, and Petersburg, unlike most other military operations of the Civil War, had more than its share of the latter. The Petersburg episode—assault and resistance—dragged on to become the longest unbroken campaign against a single city in the history of the United States. The romantic and heroic exploits were relatively few, and between them came long stretches of uninspiring and backbreaking routine.

The men of both sides had much in common, despite the bitterness with which they fought. In battle they were enemies, but in camp they were on the same common level. Stripped of the emotional tension and exhilaration of combat they all appear as bored, war-weary, homesick men. The greater part of their time was primarily concerned with digging and constructing fortifications, performing sentry and picket duty, and striving to speed up the long succession of days. They lived in rude improvised shelters, often made of mud and log walls with tent roofs.

Chimneys were made of mud and barrels. There was some friendly interchange of words and gifts between the lines, but enmity was more rampant than brotherly regard. Off duty, the amusements and pastimes of the soldiers were simple and few—limited in most cases to their ability to improvise them. The most striking difference between the armies as the Petersburg campaign lengthened was that, while the Northerners suffered most from boredom, the Confederates were plagued by the more serious and unpleasant pangs of hunger.

The Petersburg campaign, however, was grim business. Amusements could lighten the heart for only a brief time at best. Ever present were the mud and disease which followed every Civil War camp. Both opposing forces felt the chill of winter and the penetrating rain. The discouragement of the homesick, who never knew when, or if, he would return to his fireside, was not a hardship peculiar to any rank. However, when spring came to warm the air there was a difference between the two armies. It was more than a numerical superiority. Then the Union trooper felt confidence, while the Southern veteran, ill-clothed, ill-fed, and nearly surrounded, knew only despair.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |