|

MANASSAS National Battlefield Park |

|

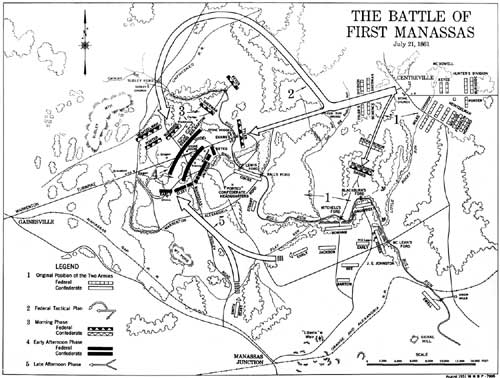

(click on the above map for a larger image)

First Battle of Manassas (see map above)

Sunday, July 21, dawned bright and clear. The listless stirring of the trees gave early promise that the day would be hot. Dust lay thick upon the grass, the brush, and the uniforms of the men. The Confederate camps were just beginning to stir from a restless night when, suddenly about 5:15 a. m., there was heard the thunderous roar of a big gun in the vicinity of the Stone Bridge. With this shot, fired from a 30-pounder Parrott rifle of Tyler's command, McDowell opened the first battle of the war.

Since 2:30 a. m. his troops had been in motion executing a well-conceived plan of attack. In bright moonlight, across the valley from Centreville "sparkling with the frost of steel," the Federal army had moved in a three-pronged attack. McDowell had originally planned to turn the Confederate right, but the affair of the 18th at Blackburn's Ford had shown the Confederates in considerable strength in that sector. Further informed that the Stone Bridge was mined and that the turnpike west of the bridge was blocked by a heavy abatis, lie determined to turn the extreme Confederate left. By this flanking movement he hoped to seize the Stone Bridge and destroy the Manassas Gap Railroad at or near Gainesville, thus breaking the line of communication between Johnston, supposedly at Winchester, and Beauregard at Manassas. To screen the main attack, Tyler was to make a feinting thrust at the Confederate defenses at the Stone Bridge, while Richardson was to make a diversion at Blackburn's Ford. Miles' division was to cover Centreville, while Runyon's division covered the road to Washington. To a large extent the success of the attack depended upon two factors—rapidity of movement and the element of surprise.

The ruins of the Stone Bridge over Bull Run, from

the east. Here opened the First Battle of Manassas.

Wartime

photograph. Courtesy National Archives.

Turning to the right at Cub Run Bridge, the main Federal column composed of Hunter's and Heintzelman's divisions, had followed a narrow dirt road to Sudley Ford which they reached, after exasperating delays, about 9:30 a. m. Here the men stopped to drink and fill their canteens. Though this loss of time was costly, success might still have been theirs if the movement had not been detected.

Sudley Springs Ford, Catharpin Run.

Wartime

photograph. Courtesy Library of Congress.

From Signal Hill, a high observation point within the Manassas defenses, the Confederate signal officer, E. P. Alexander, had been scanning the horizon for any evidence of a flanking movement. With glass in hand he was examining the area in the vicinity of Sudley Ford when about 8:45 a. m. his attention was arrested by the glint of the morning sun on a brass field piece. Closer observation revealed the glitter of bayonets and musket barrels. Quickly he signaled Evans at the Stone Bridge, "Look our for your left; you are turned." This message, which was to play an important part in the tactical development of the battle, represents probably the first use under combat conditions of the "wig-wag" system of signaling.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Apr 7 2001 10:00:00 am PDT |