|

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park |

|

"Congress Voting Independence, July 4,

1776."

Painting attributed to Robert E. Pine and Edward Savage.

Courtesy Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

"To Form a More Perfect Union"

With the return of peace in 1783 came also postwar depression. Hard times created discontent. By 1786, in Massachusetts, this flared into an open insurrection known as Shays' Rebellion. This affair (perhaps not so serious as often painted) helped point up the weakness of Congress and intensify the movement already begun to amend the Articles of Confederation. A stronger central government was needed. As a result, a convention was called by the Congress.

Christ Church (built 1727—54) where George

Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and other notables worshiped; seven

signers of the Declaration of Independence are buried in its grounds and

cemetery.

Painting by William Strickland, 1811. Courtesy

Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

Conrad Alexandre Gerard, first French Minister to the United States, who formally presented his credentials to Congress in Independence Hall on August 6, 1778. Painted by Charles Willson Peale, 1779. Independence National Historical Park collection. |

The Federal Constitutional Convention opened in Philadelphia on May 25, 1787, in the same room in the State House where the Declaration of Independence had been adopted. This room permitted the delegates to meet in secret session, which suggests the seriousness the delegates attached to their responsibilities. The Convention, composed of 55 men chosen by the legislatures of the States, was a small group, but included the best minds in America. As a matter of course, they chose George Washington to be the presiding officer; his endorsement was probably the chief factor in winning acceptance for the Constitution. The leader on the floor, and in some ways the most effective man in the Convention, was James Madison. His efforts were ably seconded by James Wilson, who deserves to be ranked with Madison on the basis of actual influence on the completed Constitution. The aged Benjamin Franklin was the seer of the group; his great service was as peacemaker of the Convention. Gouverneur Morris, brilliant and coherent debater, was responsible for the very apt wording of the Constitution in its final form. Other important delegates included George Mason, Elbridge Gerry, William Paterson, Charles Pinckney, and Roger Sherman.

The purpose of the Convention was, as stated in the Preamble to the Constitution, "to form a more perfect Union" among the States, to ensure peace at home, and to provide for defense against foreign enemies. The delegates believed that these objects could best be achieved by establishing a strong national government, but it was soon apparent that serious disagreements existed as to the nature of this proposed new government. Throughout the hot summer months, the delegates labored. The Constitution was not born at once, but developed gradually through debate, interchange of opinion, and careful consideration of problems. Many minds contributed to its final form. A body of compromises, the Constitution created the central government of a land which is both a nation and a confederation of States. It was impossible for the framers to attempt to answer all questions; much was left for future generations to define. As a result, the Constitution has proved to be a most elastic instrument, readily adaptable to meet changing conditions.

Detail sketch of rising sun on back of speaker's

chair in Assembly room.

James Madison, sometimes called "the Father of the Constitution." Painting by Charles Willson Peale (c.1792). Courtesy Frick Art Reference Library. |

James Wilson, who, with Madison, had most actual influence on the completion of the Constitution. Artist unknown. |

On September 17, 1787, 4 months after the Convention had assembled, the finished Constitution was signed "By unanimous consent of the States present." The Federal Convention was over. The members "adjourned to the City Tavern, dined together, and took a cordial leave of each other."

Often during the bitterness of debate, the Convention's outcome was in doubt. At the signing, Franklin, pointing to the gilded half-sun on the back of Washington's chair, observed:

I have often and often in the course of Session, and the vicissitudes of my hopes and fears as to its issue, looked at that [sun] behind the President without being able to tell whether it was rising or setting: But now at length I have the happiness to know that it is a rising and not a setting Sun.

Robert Morris, financier of the

Revolution.

Painting by Charles Willson Peale (c. 1782).

Independence National Historical Park collection.

Completion of work by the Federal Convention was merely the beginning of the struggle for the new Constitution; the crucial part remained. For the framework upon which the Convention had expended so much thought and labor could be made law only by the people. This was to be accomplished by submitting the document to the people for their approval or disapproval in popularly elected State conventions. This method would serve to give the Constitution a broad base of popular support. Such support was particularly necessary, since the Convention made clearly revolutionary decisions in stating that the approbation of 9 States would be sufficient for establishing the Constitution over the States so ratifying, and that the consent of the Congress was not required.

The Constitutional Convention as visualized by the

artist. Although inaccurate in detail, it is a good representation of

the delegates.

Painting by J. H. Froelich, 1935. Courtesy

Pennsylvania State Museum.

In State after State special elections were held in which the issue was whether the voters favored or did not favor the proposed Constitution. Pennsylvania's State Convention met in the State House on November 21, 1787. Under the influence of Wilson's vigorous arguments, that body ratified the Constitution on December 18. The honor of first ratification, however, went to Delaware. Her convention ratified the document unanimously 5 days earlier. Several of the smaller States adhered shortly thereafter. The sharpest contests took place in Massachusetts, Virginia, and New York where the Anti-Federalists were strong and ably led; but the advantages of the Constitution were so great that it was finally ratified in 1788 by 11 States. Rhode Island and North Carolina held out until after Washington became President.

In order to meet popular objections to the Constitution, the Federalists in Massachusetts drafted amendments which their Commonwealth, in ratifying the Constitution, might propose to the other States for adoption. This clever device helped win the struggle in several reluctant States. From these suggested amendments, intended to protect the individual citizen against the central government, the first 10 amendments to the Constitution, called the Bill of Rights, were formed. When the Constitution was finally ratified, the Congress arranged for the first national election and declared the new government would go into operation on March 4, 1789.

In 1800, Independence Hall lacked its familiar

tower, which had been removed in 1781. The present tower was erected in

1828, t which time the clock at left was taken down.

From an

engraving by William Birch. Courtesy Philadelphia Free

Library.

The new Federal Government first began its work in New York where Federal Hall Memorial National Historic Site is now located; then, in 1790, the Government came to Philadelphia. The move to Philadelphia resulted from a compromise known as the Residence Act, approved July 16, 1790. This act directed that the permanent capital was to be situated on the Potomac, but it also stipulated that the temporary seat of government was to be in Philadelphia for 10 years. Robert Morris was generally credited with bringing the capital to Philadelphia and was castigated by New Yorkers for his part in its removal from their city.

When the location of the capital was under consideration, the City and County of Philadelphia, as well as the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, offered the Federal Government the use of the City Hall and the County Courthouse, two new buildings then under construction. These buildings fulfilled the original plan of a governmental center as conceived by Andrew Hamilton. The offer was accepted and for the last 10 years of the 18th century the United States Congress sat in the new County Courthouse (now known as Congress Hall), on the west side of the State House, and the U. S. Supreme Court, in the new City Hall (Supreme Court Building), on the east.

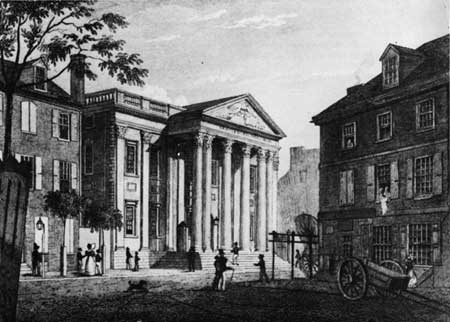

First Bank of the United States, built in

1795.

Engraving by Fenner Sears after C. Burton, 1831. Courtesy

Philadelphia Free Library.

The building in which the Supreme Court sat from 1791 on was erected by the City of Philadelphia to accommodate the growth of municipal departments and functions. During the Colonial period the city government occupied the small courthouse at Second and High (now Market) Streets. When the Federal Government came to Philadelphia, the new building was not yet completed, and the Supreme Court of the United States met first in the Pennsylvania Supreme Court Chamber in the State House. After August 1, 1791, the Supreme Court generally occupied the Mayor's Court, the large room at the south end of the first floor, in the new City Hall. It is possible that the corresponding room on the second floor was also used on occasions by the high tribunal. During its occupancy of the building, the Supreme Court was first presided over by John Jay, who was succeeded in turn as Chief Justice by John Rutledge and Oliver Ellsworth. Here the court began its active work, thereby laying the foundation for the development of the Judicial Branch of the Federal Government.

The ground on which Congress Hall stands was purchased for the Province of Pennsylvania in 1736. Although there had been plans for a long time to erect a courthouse on the lot, it was not until 1785 that the Assembly of Pennsylvania passed an act to appropriate funds for the erection of the building. Work began in 1787 and was completed in 1789. This county court building became the meeting place of the first United States Congress, Third Session, on December 6, 1790. Frederick Augustus Muhlenberg was then Speaker of the House and John Adams, President of the Senate. It is today the oldest building standing in which the Congress of the United States has met.

Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury in Washington's administration, whose comprehensive program placed the new Nation on a firm financial basis. Painting by Charles Willson Peale (c. 1791). Independence National Historical Park collection. |

Before the courthouse could be turned over to the United States Congress, alterations had to be made to fit the building for its new purpose. The first-floor chamber, to be used by the House of Representatives, was furnished with mahogany tables and elbow chairs, carpeting, stoves, and venetian blinds—all of fine workmanship. In addition, a gallery was constructed to hold about 300 people. The Senate Chamber on the second floor was even more elegantly furnished.

Then, between 1793 and 1795, to accommodate the increase in membership of the House from 68 to 106, the building had to be enlarged by an addition of about 26 feet to the end of the original structure. In 1795, a gallery was constructed for the Senate Chamber similar to, although smaller than, the one on the floor below.

The decade during which Philadelphia served as the capital was a formative period for our new Government. In foreign relations, the Citizen Genet affair and other repercussions of the French Revolution, which brought near-hostilities with France, ended the historic Franco American Alliance of 1778. It is impossible to list all the great events which occurred during that period, but among them must be mentioned the inauguration of Washington for his second term in the Senate Chamber on March 4, 1793. At the same time John Adams assumed the Presidency of the Senate. Washington delivered his last formal message before Congress, prior to retiring, in the chamber of the House of Representatives on December 7, 1796. It is this message which some have confused with Washington's famous Farewell Address.

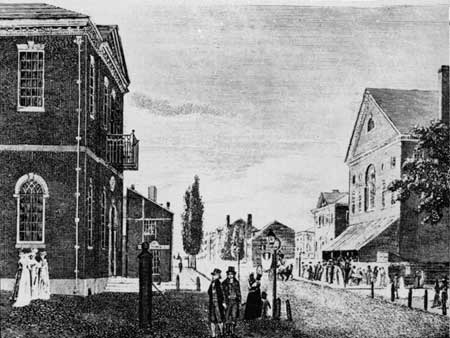

Congress Hall (looking west along Chestnut Street)

near the turn of the century when Philadelphia ceased to be the capital

city and the building reverted to use as a county courthouse. In right

foreground is old Chestnut Street Theater.

Engraving by William

Birch, 1799. Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library.

It was in Congress Hall that the first 10 amendments—the Bill of Rights—were formally added to the Constitution. It was here also that the First Bank of the United States and the Mint were established as part of the comprehensive program developed by Alexander Hamilton, Secretary of the Treasury, to rectify the disordered state of Government finances. Here, too, Jay's Treaty with England was debated and ratified; Vermont, Kentucky, and Tennessee were admitted into the Union; and the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed. And it was here that the Federal Government successfully weathered an internal threat to its authority—the Whiskey Insurrection of 1794.

In the chamber of the House of Representatives, John Adams was inaugurated as second President of the United States on March 4, 1797. Two years later, official news of the death of Washington was received here by Congress, at which time John Marshall introduced Henry ("Light-Horse Harry") Lee's famous words: "First in War, First in Peace, First in the Hearts of his Countrymen."

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |