|

INDEPENDENCE National Historical Park |

|

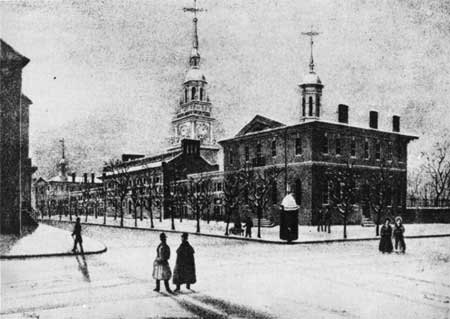

Independence Hall group in the winter of 1840.

(Note restored steeple and clock, also doorway on Sixth Street side of

Congress Hall.)

Lithograph by J. T. Bowen after drawing by J. C.

wild, 1840. Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library.

Evolution of a Shrine

The "State House" did not become "Independence Hall" till the last half of the 19th century. This change in designation, which began about the time of Lafayette's visit to America, is closely linked with the evolution of the building as a national shrine.

Prior to 1824, there was but little reverence or regard for the State House. The visit of the Marquis de Lafayette to Philadelphia in that year, however, awakened an interest in the building which has persisted to this day.

Elaborate preparations were made for the visit of the celebrated friend of America, much of it centering around the State House, which became the principal point of interest. Across Chestnut Street, in front of the building, was erected a huge arch "constructed of frame work covered with canvas, and painted in perfect imitation of stone." The old Assembly Room, called for the first time "Hall of Independence," was completely redecorated. The walls and ceiling were painted stone color, and windows were "hung with scarlet and blue drapery studded with stars." Portraits of Revolutionary heroes and the Presidents virtually filled the available wall space. Mahogany furniture was "tastefully and appropriately disposed."

Lafayette was formally received in the "Hall of Independence" by the Mayor and other dignitaries on September 28. On the days following, during his week-long visit, the chamber served as his levee room.

The interest in the State House engendered by Lafayette's visit was not permitted to die. In 1828, the City Councils obtained plans and estimates to rebuild the wooden steeple which had been removed in 1781. After heated discussions, William Strickland's design for the new steeple was accepted, a large bell to be cast by John Wilbank was ordered, and Isaiah Lukens was commissioned to construct a clock. Work was completed on the project during the summer of 1828.

Strickland's steeple was not an exact replica of the original, but it may be considered a restoration since it followed the general design of its predecessor. The principal deviations were the installation of a clock in the steeple and the use of more ornamentation.

Earliest known photograph of Independence Hall, taken in 1850 by W. and F. Langenheim. From their "Views in North America" series. Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library. |

Within 2 years after rebuilding the steeple, interest was aroused in the restoration of the Assembly Room, or "Hall of Independence." On December 9, 1830, the subject of the restoration of this room "to its ancient Form" was considered by the Councils. Shortly afterward, John Haviland, architect, was employed to carry out the restoration. Apparently, Haviland confined his work to replacing the paneling that is said to have been removed and preserved in the attic of the building.

The proper use of the room was always a knotty problem. Following the Haviland restoration, the room was rented on occasions for exhibiting paintings and sculpture. Its principal use, however, was as a levee room for distinguished visitors, including Henry Clay, Louis Kossuth, and other famous personages, in addition to many Presidents of the United States from Jackson to Lincoln.

In the 1850's, and during the critical years of the Civil War, veneration for the State House became even more evident. In 1852, the Councils resolved to celebrate July 4 annually "in the said State House, known as Independence Hall . . ." This is the first clear-cut use of the term "Independence Hall" to designate the entire building.

Perhaps the best expression of this veneration is in the grandiloquent words of the famed orator Edward Everett, who, on July 4, 1858, said of the State House, or as it has now come to be known, Independence Hall: "Let the rain of heaven distill gently on its roof and the storms of winter beat softly on its door. As each successive generation of those who have benefitted by the great Declaration made within it shall make their pilgrimage to that shrine, may they not think it unseemly to call its walls Salvation and its gates Praise."

Independence Hall group in 1853.

Engraving

of a drawing by Devereux. Courtesy Philadelphia Free

Library.

On July 4, 1852, the delegates from 10 of the Thirteen Original States met in Independence Hall to consider a plan to erect in the square one or more monuments to commemorate the Declaration of Independence. For various reasons, their deliberations proved fruitless.

During the years after the restoration of the Assembly Room in 1831, a few paintings and other objects were purchased by, or presented to, the City for exhibition. One of the first acquisitions was the wooden statue of George Washington, by William Rush, which long occupied the east end of the room. It was not until 1854, however, that the City made any real effort to establish a historical collection for Independence Hall. In that year, at the sale of Charles Willson Peale's gallery, the City purchased more than 100 oil portraits of Colonial, Revolutionary, and early Republican personages.

Following the acquisition of Peale's portraits, the Assembly Room was refurnished and these paintings hung on the walls. On February 22, 1855, the Mayor opened the room to the public. From that day on, many relics and curios were accepted by the City for display in this chamber.

During the Civil War, the "Hall" (or Assembly Room) served a solemn purpose. From 1861 on, the bodies of many Philadelphia soldiers killed in the war, and, in 1865, the body of President Lincoln lay in state there. Such use of the room was not new, however, for John Quincy Adams, in 1848, Henry Clay, in 1852, and the Arctic explorers Elisha Kent Kane, in 1857, lay in state in the venerable room.

In 1860, a movement was begun by the children of the public schools of Philadelphia to erect a monument to Washington. When the fund was nearly raised, the Councils provided a space on the pavement directly opposite the Chestnut Street entrance. The statue, executed by J. A. Bailey, was unveiled on July 5, 1869.

In 1855, the Assembly Room became a portrait

gallery, following acquisition by the City of Charles Willson Peale's

oil paintings of Colonial and Revolutionary figures. (Note Liberty Bell

on ornate pedestal in corner and Rush's wooden statue of Washington in

center background.)

Engraving from Illustrated London

News, December 15, 1860. Independence National Historical Park

collection.

Little beyond actual maintenance of the buildings seems to have occurred until 1872 when, with the approach of the Centennial of the Independence of the United States, a committee for the restoration of Independence Hall was named by the Mayor. The committee entered upon its duties with energy. Furniture believed to have been in the Assembly Room in 1776 was gathered from the State Capitol at Harrisburg and from private sources. Portraits of the "founding fathers" were hung in the room. The president's dais was rebuilt in the east end of the room, and pillars, thought to have supported the ceiling, were erected. The red paint which had been applied to the exterior of the building was removed from the Chestnut Street side. When accumulated layers of paint were removed from the first floor interior walls, the long-hidden beauty of carved ornamentation was again revealed.

During the Centennial restoration project, a large bell (weighing 13,000 pounds) and a new clock were given to the City by Henry Seybert for the steeple of Independence Hall. This clock and bell are still in use.

The body of Elisha Kent Kane, Arctic explorer,

lying in state in the Assembly Room of Independence Hall, 1857.

Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library.

With the close of the Centennial celebration, Independence Hall experienced a period of quiet, disturbed only by the increasing numbers of visitors. Then toward the close of the 19th century, another restoration cycle began, but its emphasis was quite different from that of any in the past. Except for the replacement of the steeple in 1828, all restoration work heretofore had been concentrated in the east or Assembly Room on the first floor. Finally, in the 1890's interest extended from the Assembly Room to the remainder of the building. An ordinance of the Common and Select Councils, approved by the Mayor on December 26, 1895, called for the restoration of Independence Square to its appearance during the Revolution. A committee of City officers concerned with public buildings and an advisory committee of leading citizens were named by the Mayor to carry out the work. On March 19, 1896, a resolution of the Councils granted permission to the Philadelphia Chapter of the Daughters of the American Revolution to proceed with the restoration of the old Council chamber on the second floor of Independence Hall.

Lithograph of Independence Hall in 1876. (Note

Bailey's statue of Washington opposite Chestnut Street

entrance.)

Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library.

Between 1896 and 1898, the committees and the Daughters of the American Revolution carried out a most extensive program of restoration. The office buildings designed by Robert Mills were replaced by wings and arcades which were more like those of the 18th century. The first-floor rooms of Independence Hall were restored, and the Daughters of the American Revolution attempted to restore the entire second floor to its Colonial appearance by reconstruction of the long room, the vestibule, and the two side rooms. A dummy clockcase, similar to that of the Colonial period, was rebuilt outside on the west wall, but the planned moving of the clock back to its 18th-century location was not carried out. With the completion of this work, the old State House had been restored to a close approximation of its original design. For the first time in almost a century the building appeared practically as it did during the American Revolution.

During the 19th century, the program of restoration and preservation had been concerned largely with work on Independence Hall, little thought having been given to the entire group of historical structures on the square. In fact, according to an act of the General Assembly approved August 5, 1870, the other buildings on the square were to be demolished. Fortunately, this act was never carried out; it was finally repealed in 1895.

With the 20th century, emphasis shifted from Independence Hall to the remainder of the group. Although some restoration work had been done in Congress Hall by the Colonial Dames of America in 1896, their efforts were confined to the Senate chamber and to one of the committee rooms on the upper floor. Additional restoration of Congress Hall was not undertaken until the American Institute of Architects became interested in the matter. In 1900, the Philadelphia Chapter of this organization made a study of the documentary evidence available on the building and began an active campaign for its restoration. Finally, in 1912, funds became available and the City authorized the beginning of work under the auspices of the Philadelphia Chapter. This was completed in the following year, and President Wilson formally rededicated the building. In 1934, additional work was done in the House of Representatives chamber.

Restored Assembly Room of Independence Hall, 1876.

(Note President's dais at far end of room, tile floor, and

pillars—then thought to have supported the ceiling.)

Courtesy Philadelphia Free Library.

The restoration of Congress Hall at Sixth Street brought into sharp contrast the condition of the Supreme Court building (Old City Hall) at Fifth Street. For many years the American Institute of Architects and other interested groups urged the City to complete restoration of the entire Independence Hall group by working on the Supreme Court building. This phase of the program, delayed by World War I, was not completed until 1922.

With the completion of restoration projects, the buildings on Independence Square presented a harmonious group of structures in substantially the appearance of their years of greatest glory. The neighborhood in which they were situated, however, had degenerated into a most unsightly area. Therefore, the improvement of the environs of Independence Hall, containing a large concentration of significant buildings, was the next logical development.

This movement to preserve the historic buildings in Old Philadelphia, and incidentally to provide a more appropriate setting for them, had long been considered. During World War II, the nationwide movement for the conservation of cultural resources became particularly active in Philadelphia, and much was done to coordinate the work of different groups. In 1942, a group of interested persons, including representatives of more than 50 civic and patriotic organizations, met in the Hall of the American Philosophical Society and organized the "Independence Hall Association." This association was the spearhead of a vigorous campaign which resulted in stimulating official action to bring about the establishment of Independence National Historical Park Project.

The Banquet, or "Long, Room of

Independence Hall with portrait gallery.

Conceived as a means of reclaiming some of the neighborhood around Independence Square and to preserve the many significant historical buildings in the area for the benefit and enjoyment of the American people, the historical park is being developed by the concerted efforts of the City of Philadelphia, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, and the United States of America.

Assembly Room of Independence Hall, 1956, after

restoration by the National Park Service.

In 1945, the State Government authorized the expenditure of funds to acquire the three city blocks between Fifth and Sixth Streets from the Delaware River bridgehead at Race Street to Independence Square. This project of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, officially designated "Independence Mall," provides for the demolition of almost all buildings within the authorized area to make room for a great concourse, thereby forming a dignified approach to Independence Square. By the summer of 1956, all buildings in the first block and part of the second, between Chestnut and Commerce Streets, had been demolished and the ground landscaped.

The Federal area was defined by an act of the Congress (Public Law 795, 80th Congress) after the matter had been studied intensively by a Federal commission named in 1946. The principal area covers three city blocks between Walnut and Chestnut from Fifth to Second Streets, with subsidiary areas on either side to include important historic sites, such as the property adjacent to old Christ Church, the site of Franklin's home, and an area leading from Walnut Street to Marshall's Court. A surprising number of significant buildings are included within the park boundaries. The First and Second Banks of the United States, the Philadelphia Exchange, and the Bishop White and Dilworth-Todd-Moylan houses are the principal historic buildings included in the Federal area. Carpenters' Hall and Christ Church will not be purchased, but their preservation and interpretation have been assured through contracts with the Department of the Interior.

Detail of restored Assembly

Room.

The contribution of the City of Philadelphia to the historical park is by far the most vital. On January 1, 1951, the custody and operation of the Independence Hall group of buildings and the square were transferred, under the terms of a contract, from the City to the National Park Service. The title to the property will remain with the City. Earlier, in 1943, the buildings were designated a national historic site by the Department of the Interior. Since assuming custody of the Independence Hall group, the National Park Service has carried out an extensive program of rehabilitation of these historic structures; also, many facilities for visitors have been provided for the dissemination of the history of the Independence Hall group, as well as that of the other structures in the park. In addition, a far-reaching project of historical and architectural research has been undertaken. The facts gathered in this research will enable plans to be developed which will assure the public of deriving the maximum benefit from a visit to this most important historical area.

It is fortunate that these old structures have survived, sometimes through accident rather than design, so that they may serve as tangible illustrations of this Nation's history for the inspiration of this and succeeding generations of Americans.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |