|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

"Sioux Fighting Custer's Battalion." Drawn by the Sioux Chief

Red-Horse.

(From the Tenth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology,

Smithsonian Institution.)

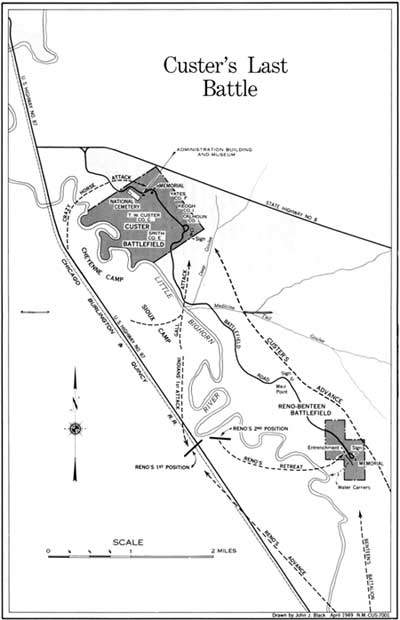

Custer's Last Battle

Much has been written about the Custer phase of the battle, but very few facts can definitely be stated. Custer's route, after he was last seen with Company E (Gray Horse Company) on a high promontory over looking the river bottom where Reno was engaging the Indians, is still shrouded in mystery. As he looked down from the bluffs at the battle between Reno's troops and the Indians, he was seen by some of these troops to wave his hat as in encouragement.

During the time Custer disappeared from the bluffs and descended for a short disrance, probably down the deep ravine near Medicine Tail Coulee, Reno had started his retreat from his position on the river flat to seek higher ground for defensive purposes. Perhaps about the time Reno left the river bottom, Custer and his troops reached a point across the Little Bighorn River from the main Indian camp. The attack against Reno's troops had eased off, and the mass of Indians immediately started after the Custer column. There were only about 225 cavalrymen against warriors numbering possibly up to 5,000. This was more than the small body of troopers could withstand, and the cavalrymen were gradually pushed to the positions now indicated by the silent white markers that dot Custer Hill.

Custer and his two-hundred-odd troopers on this hill fought one of the bloodiest battles with the Indians in the annals of American history. Many of the horses that had brought these troopers nearly 1,000 miles were shot to make breastworks against the deadly bullets and arrows from the Sioux and Cheyenne warriors.

It is thought that not long after the Indians began to show a strong force in Custer's front, he turned his column to the left and advanced in the direction of the Indian village to the junction of two ravines just below a spring. Here he probably dismounted two companies, under command of Keogh and Calhoun, to fight on foot. It is quite possible that the companies advanced to a knoll, now marked by Crittenden's marker, while the remaining three mounted companies continued along the ridge to Custer Hill.

The line occupied by Custer's battalion was the first considerable ridge back of the river. His front was extended about three-fourths of a mile. Most of the Indian village was in view. A few hundred yards from his line was another, but lower, ridge, the further slope of which was not commanded by his line. It was from here that the Indians, under Crazy Horse, from the lower part of the encampment, part of whom were Cheyennes, moved on Custer and cut off all access to the village. Gall and his warriors had been the first to meet Custer.

Many of the participants on both sides were on foot and doing much fighting from prone positions on the ground. The warriors outnumbered Custer's men possibly as much as 20 to 1. The horde of Indians were wriggling along gullies and hiding behind knolls on all sides of the troops. One need only to walk over the battlefield today and observe the terrain to understand how well they could hide themselves from the fire of the soldiers.

The only accounts of the battle have come from the Indians, since there were no surviving whites; but, because of the circumstances, much of what happened may never be solved conclusively. The fighting may have lasted about an hour, although the exact duration will never be known. The Indians managed to start the troopers' horses into a stampede, and many were caught by the Indian women in the valley. Some of these horses carried extra ammunition in their saddlebags. It is thought that Custer's men had some of the extra ammunition in their possession before the stampede occurred, but the loss may have seriously affected others.

The horse stampede was followed quickly by a concerted attack by the Indians which was so successful and so swiftly carried out that not a Custer trooper remained alive. The Indians stated that not one prisoner was taken alive and that they were not trying to capture any of them as prisoners. They also stated that there was no final charge on horseback such as often has been represented in writings and paintings. The only semblance to such culminating action was a "charge" by the mounted Indians youths and old men in a rush to seize plunder from the dead bodies of Custer's men.

Custer's Last Battle.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |