|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

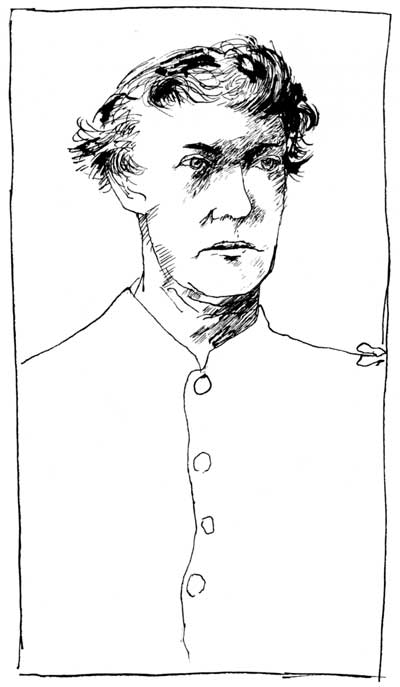

Capt. Frederick W. Benteen.

Reno Attacks

Shortly after noon on June 25, 1876, the 7th Cavalry topped the divide and paused at the head of the stream that later took the name Reno Creek. Here Custer had his adjutant, Lt. W.W. Cooke, form the regiment into three battalions. Major Reno took command of one, consisting of Companies A, G, and M— perhaps as many as 140 men, although straggling later reduced the number somewhat. Capt. Frederick W. Benteen headed the second, consisting of Companies H, D, and K, about 125 men. Custer himself retained five companies, C, E, F, I, and L, about 215 men. Capt. Thomas McDougall was assigned with B Company to guard the packtrain.

Perhaps still conscious of Terry's strictures about preventing the flight of the hostiles to the southeast, Custer at once ordered Captain Benteen to lead his battalion in that direction, along the base of the Wolf Mountains, and to "pitch into anything he might find." As Benteen's column wheeled to the left, Custer and Reno, placing their battalions on opposite sides of the creek, took up the march down the narrow valley toward the Little Bighorn. The Indian scouts preceded the advance, and the packtrain followed in the rear.

A march of about 10 miles brought Custer and Reno, by 2:15 p.m., to within 4 miles of the Little Bighorn. Here, at an abandoned Sioux campsite, the troops flushed a party of about 40 warriors, who raced their ponies toward the river. Beyond, a great cloud of dust rose from behind a line of bluffs that hid the Little Bighorn Valley north of the mouth of Reno Creek.

Custer had now discovered the enemy. The dust probably signified to him that the village lay behind the bluffs and that its occupants were trying to get away. Even though Benteen could not be called upon, the situation demanded an immediate attack. Instantly, Custer ordered Reno to pursue the fleeing warriors, "and charge afterward, and you will be supported by the whole outfit."

At this point Custer may have intended to support Reno by following him into battle with the five companies under his personal leadership. As Reno's battalion and the Arikara scouts forded the river, however, they saw in the distance swarms of Indians apparently riding up the valley to give battle. Fred Gerard, a civilian interpreter, knew that Custer supposed the Indians to be fleeing. He turned back on the trail and overtook Lieutenant Cooke and another officer who had accompanied Reno as far as the river. Explaining that the Indians were not fleeing at all but were coming out to fight, Gerard wheeled to rejoin Reno.

Reno's battalion advanced down the Little Bighorn Valley at a trot. Two miles ahead lay the objective. A few tepees marking the upper end of the Sioux encampment could be faintly seen through the dust clouds. Horsemen in growing numbers swarmed forth from the village to meet the attack. Reno ordered a charge, and the line broke into a gallop. Anxiously the major looked back for the support Custer had promised, but none appeared. Another one-half mile and the soldiers would be swallowed by perhaps seven times their number of aggressive warriors. Reno threw up his hand and shouted the command to fight on foot.

Within sight of the first tepees of the village the charge ground to a halt. A thin skirmish line stretched part way across the valley. Mounted Sioux raced the length of the line, curled around the left flank, and appeared in the rear. Within 15 minutes the position had grown untenable. Reno flanked right into the timber, but in the heavy undergrowth he lost control of his companies. Warriors worked through the brush and trees and gathered on the other side of the river to fire from the rear. Within half an hour, closely pressed and running low on ammunition, the major decided that the new position could not be held either.

The high bluffs across the river appeared to offer the only refuge from the encircling tribesmen. Reno ordered his men into the open, mounted them in a loose column formation, and led a charge toward the river. The retreat verged on a panic rout as masses of Sioux closed in on the handful of troopers. At the river no one organized a force to cover the crossing, and warriors clustered on the bank to fire at the struggling soldiers in the water. Those who reached the east side made their way up the ravines that cut into a rampart of bluffs rising steeply to a height of 300 feet above the water.

Exhausted and beaten, the remnant of the battalion gathered atop the bluffs. Of about 130 men who had entered the fight, 33 had been killed. Among them were Lt. Donald McIntosh, Lt. B. H. Hodgson, Dr. J. M. DeWolf, and the famed scout "Lonesome" Charley Reynolds. Many more were wounded, and Lt. C. C. DeRudio and 16 men were missing. They had not heard the order to retreat and had been left in the timber. Fortunately for them and for the survivors on Reno Hill, the Indians almost immediately relaxed the pressure, and soon they had seemingly withdrawn altogether.

It was now late afternoon, perhaps shortly after 4 p.m. Knots of officers and men anxiously speculated over the whereabouts of Custer.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |