|

LITTLE BIGHORN BATTLEFIELD National Monument |

|

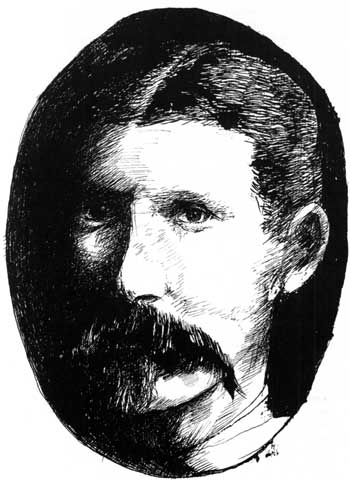

Capt. Myles W. Keogh.

Rescue

On Reno Hill the cavalrymen watched the exodus from the valley and speculated on its meaning. None knew what had happened to Custer. None knew why the Indians were leaving. None could shake the fear that the next morning would bring fresh waves of warriors against the hilltop. During the night the troops buried their dead and moved closer to the river. Lieutenant DeRudio and most of the soldiers and scouts left in the timber the day before made their way into the lines. They had remained concealed for a harrowing 36 hours while Indians came and went nearby.

Next morning a blue column was seen marching up the valley. Some thought it was Custer at last. Others thought it Terry. A few speculated that it was Crook. Two officers rode out to investigate. A short gallop brought them to the leading ranks of the 2d Cavalry, General Terry in the van. Both general and lieutenants burst out with the same question: "Where is Custer?"

Lt. James H. Bradley brought the answer. He and his Crow scouts had counted 197 bodies, most of them stripped of clothing and badly mutilated, littering the battle ridge 4 miles downstream. Custer's body lay just below the crest at the north end of the ridge. It had been stripped but neither scalped nor mutilated. One bullet had lodged in the left breast, another in the left temple.

Of about 215 officers and men in Custer's battalion, not one had survived although the failure to find all the bodies left a faint possibility that someone may have escaped. In Reno's retreat from the valley and defense of the bluffs, another 47 men had been slain and 53 wounded. Altogether, half the regiment lay dead or wounded. How many Indians paid for this victory with their lives will never be known, for the dead were borne off by the living. Estimates vary from 30 to 300.

On the morning of June 28, Reno's 7th Cavalrymen rode to the Custer battlefield for the sad chore of interring the dead. Tools were few, and in most cases the burial details simply scooped out a shallow grave and covered the body with a thin layer of sandy soil and some clumps of sagebrush. The officers were buried more securely and the graves plainly marked for future identification.

Meanwhile, Gibbon's troops improvised hand litters to carry Reno's wounded the 15 miles to the mouth of the Little Bighorn, where they were to be placed on the Far West and transported to Fort Lincoln. The hand litters proved too awkward and on the 29th were replaced with mule litters. On the morning of June 30 Captain Marsh received the wounded on the steamer deck, where they were laid on a bed of freshly cut grass. Cautiously Captain Marsh piloted the Far West down the shallow Bighorn to its mouth, paused for 2 days awaiting Terry and Gibbon, then ferried the command to the north side of the Yellowstone. On July 3 Marsh eased his craft into the muddy current for an epic voyage that would become legendary in the history of river steamboating. Down the Yellowstone and Missouri the vessel sped. At 11 p.m. on July 5, draped in black mourning cloth, the Far West nosed into the Bismarck landing. Marsh had set a speed record never to be topped on the Missouri—710 miles in 54 hours.

The crew ran about the town spreading word of the Custer disaster. Captain Marsh hastened to the telegraph office, where the operator, J. M. Carnahan, seated himself at the key and tapped out a terse message confirming the rumors that had already begun to filter across the Nation. It was the first of a series of dispatches that by the end of the next day totaled 50,000 words. Meanwhile, the Far West dropped down to Fort Lincoln. The wounded were carried ashore and placed in the post hospital.

In the predawn gloom of July 6, officers went from house to house rousing the occupants from bed and breaking the tragic news to the widows of the officers and men who had fallen with Custer.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |