|

JAMESTOWN National Historic Site |

|

The Story of Jamestown

On May 13, 1607, three small English ships approached Jamestown Island in Virginia—the Susan Constant of 100 tons commanded by Capt. Christopher Newport and carrying 71 persons; the Godspeed of 40 tons commanded by Capt. Bartholomew Gosnold and carrying 52 persons; and the Discovery, a pinnace, of 20 tons under Capt. John Ratcliffe, carrying 21 persons. During the day (as George Percy, one of the party on board, relates) they maneuvered the ships so close to the shore that they were "moored to the Trees in six fathom [of] water." The next day, May 14, he continues, "we landed all our men, which were set to worke about the fortification, others some to watch and ward as it was convenient." Thus, the first permanent English settlement in America was begun on the shores of the James River, in Virginia, about 20 years after the ill-fated attempts to establish a colony on Roanoke Island and 13 years before the Pilgrims made their historic landing at Plymouth, in New England.

THE ENGLISH BACKGROUND. The settlement at Jamestown, in 1607, was another step, albeit a most significant step, in England's quest for a place in the vast New World first indicated by Columbus in his discovery of 1492 and made known to Europe through his and other expeditions. King Henry VII of England early sought to establish a claim in North America and sponsored the now famous voyage of John and Sebastian Cabot in 1497. The Cabots touched points along the Atlantic coast, and their discoveries were ever afterward pointed to with pride by Englishmen discussing their rights in the New World. As William Strachey wrote, in 1612, ". . . our voyages hither for a while might seeme to lye slumbering, yet our tytle could not thereby out sleepe ytself . . .". Despite this, England was occupied at home and in Europe and did not press this advantage. Spain took the lead in colonial settlement and held it for decades. How many Englishmen set foot on the North American continent in the first three-quarters of the 16th century may never be known. They were no strangers in the fishing waters off Newfoundland, and in this region there appear to have been landings and temporary settlements. Even so, serious attempts at colonization did not begin until the reign of Queen Elizabeth, and then it was pushed vigorously by men of the mark of Sir Humphrey Gilbert, Sir Walter Raleigh, and their associates.

Sir Humphrey lost his life in 1583 when returning from his attempted settlement of St. John's Port, Newfoundland. Sir Walter Raleigh diligently sought to establish the English flag to the south. He sent out two colonial expeditions to found a settlement on Roanoke Island in present eastern North Carolina. Both failed in their over-all purpose. It was the expedition of 1587 (the last) which set sail for the Chesapeake Bay country and landed on Roanoke Island that has come down to us as the "Lost Colony"—the settlement that saw the birth of Virginia Dare and that left the baffling inscription suggesting that the members of the colony moved, willingly or unwillingly, to be with the Croatan Indians who lived not far from Roanoke. The early men at Jamestown knew of their countrymen who were lost in America and were under orders to seek them. This they did, but their search went unrewarded.

By 1600, England was readying herself for a concerted drive to establish colonies in the New World. The way had been prepared by the farsighted Queen Elizabeth and her supporters. Within England there had been growth; capital had accumulated; industry was taking root; commercial organization was beginning; and Englishmen were ready for new adventures. Outwardly, England had grown through its naval successes and had developed a keen hostility to Spain. Individual Englishmen, each depending on his own circumstances, were seeking more profitable employment, personal freedom (particularly religious liberty), land ownership, personal advancement, adventure, and just plain change. A new England was in the making and the British Empire was about to rise in the West and in the Orient as well. With the accession of James I to the English throne, peace was made with Spain, a peace that was maintained although it was an uneasy one—from time to time little more than an armed truce. Yet, because of it, English capital came out of hiding and sought profitable investment. Business development increased and joint stock companies began to organize for overseas settlement.

Colonization was expensive, however, and required the pooled resources of many men. Advertising, which reached a peak early in the 17th century, was put to work in a manner that would do credit to the present day. Its use in commerce and government is by no means of recent date. Spokesmen—speakers, writers, poets, pamphleteers, play wrights, and preachers—solicited all England to take part in these new endeavors which, in their words, gave every assurance of profitable return.

The exploits of men such as Raleigh and Gilbert, Martin Frobisher, Michael Lok, John Davis, Thomas Cavendish, Sir Francis Drake, and Sir John Hawkins had already made England conscious of the potentialities of the New World and of the need to seek a part of it. Others followed these earlier leaders. In 1602 Raleigh sent yet another ship under Samuel Mace to seek the lost settlers of Roanoke, and in the same year a vessel went out under Bartholomew Gosnold who attempted a settlement on Elizabeth's Island in present Massachusetts. Gosnold and another in this party, Gabriel Archer, were to become prominent later in the Jamestown settlement. In 1603, Martin Pring made a voyage along the northern part of Virginia. In 1605, came the expedition under George Weymouth to the Kennebec River on the New England coast. He spent some weeks here and returned to England carrying with him several Indian natives from that region.

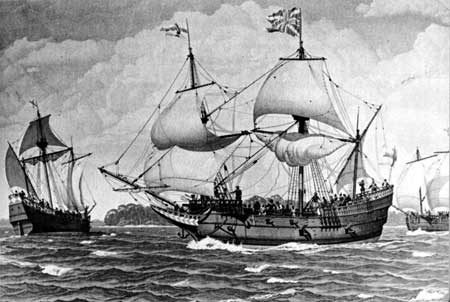

The arrival of the settlers at Jamestown in 1607.

(A painting by Griffith Baily Coale in the State Capitol, Richmond,

Va.)

On April 10, 1606, the first Virginia charter received the great seal of England. This document recognized two groups and two spheres of influence that would fall between the thirty-fourth and forty-fifth parallels of north latitude along the American coast. One was interested in North Virginia and was granted to Thomas Hanham, Raleigh Gilbert, William Parker, George Popham, and others of and for Plymouth and other English places. This group was first in the field with exploration, dispatching a ship in August 1606 under Henry Challons. In May 1607, they sent a colony to the mouth of the Kennebec in Maine, but, in the spring of 1608, after a severe winter, the settlement was given up.

The second group, organized under the charter of 1606, was that interested in south Virginia. This patent went to Sir Thomas Gates, Sir George Somers, Richard Hakluyt, Edward Maria Wingfield, and others of and for the city of London. The treasurer of the group was Sir Thomas Smith, one of the most capable businessmen of the day. Richard Hakluyt, the foremost authority on travel, foreign regions, and colonization in general, assembled helpful data and had a large part in the preparation of instructions and orders for those to be sent our as colonists. It was this group and their associates that organized, financed, and directed the expedition that reached Jamestown on May 13, 1607, and saw to it that supplies came through and reinforcements were procured in the lean years of the settlement.

The immediate and long-range reasons for the settlement were many and, perhaps, thoroughly mixed. Profit and exploitation of the country were expected, for, after all, this was a business enterprise and they were necessary for long-range activity. A permanent settlement was the objective. Support, financial and popular, came from a cross section of English life. It seems obvious from accounts and papers of the period that it was generally thought that Virginia was being settled for the glory of God, for the honor of the King, for the welfare of England, and for the advancement of the Company and its individual members. In England and in Virginia they expected and did carry the word of God to the natives, although not with the same verve as the Spanish. They expected to develop natural resources, to free the mother country from dependence on European states, to strengthen their navy, and to increase national wealth and power. They expected to be a thorn in the side of the Spanish Empire; in fact, they hoped one day to challenge and overshadow that empire. They sought to find the answer to agricultural unemployment at home. They sought many things, not the least of them being gold, silver, and land. As the men stepped ashore on Jamestown Island, perhaps each had a slightly different view of why he was there, yet some one or a combination of these motives was probably the reason.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |