|

JAMESTOWN National Historic Site |

|

The Story of Jamestown (continued)

BRICK ARCHITECTURE. When Governor Harvey reached Jamestown in January 1637 he made a special effort to promote the growth of the town. The assembly passed an act offering a "portion of land for a house and garden" to every person who would undertake to build on it within 2 years. This was the beginning of considerable activity at Jamestown. A number of new patents were issued, and, in January 1639, the governor and his council could report that 12 houses and stores had been constructed and others had been begun. One of those already built was the house of Richard Kemp, secretary of the colony. His house was described as "one of brick" and "the fairest ever known in this country for substance and uniformity. " Kemp's house is the earliest all-brick house in Virginia that it has been possible to date conclusively up to the present time. It was in 1639, too, that the first brick church was begun, and a levy was collected for the acquisition of a statehouse. Among the new land holders at Jamestown in this period of activity were Capt. Thomas Hill, Rev. Thomas Hampton, and Alexander Stoner, a "brick-maker." As the area along the river was occupied, additional patentees obtained holdings just outside of the town proper and others settled in the few lots that were not in use. Sir William Berkeley, who became governor in 1641, continued the emphasis on the construction of substantial houses. In that same year, the colony acquired its first state house, formerly the property of Harvey and a building in which public business had been transacted for, perhaps, as much as 10 years.

In March 1646, measures were taken to discourage the sale of liquors on the island, and a system of licensed ordinary keepers was adopted. Later in the year, houses for the encouragement of linen manufacture were projected for Jamestown. In 1649, the General Assembly established a market and near the market area was the landing for the ferry that ran across the James to Surry County. Even this new action, however, failed to develop a town of any great extent. The same was true of the Act of 1662 which attempted to encourage a substantial building program for the capital town. Only a few houses were erected before the new impetus had spent itself, and, in 1676, it is known that the town was still little more than a large village. One of the more detailed descriptions at this time relates that "The Towne . . . [extended] east and west, about 3 quarters of a mile . . . [and] comprehended som[e] 16 or 18 houses, most as is the church built of brick, faire and large; and in them about a dozen families (for all the howses are not inhabited) getting their liveings by keeping of ordnaries, at extreordnary rates."

THE COMMONWEALTH PERIOD. The decade of 1650—60 corresponds to the period of the Commonwealth Government in England. Virginia, for the most part, appeared loyal to the crown, yet in 1652 the colony submitted to the new government when it demonstrated its power before Jamestown. Governor Berkeley withdrew to his home at Green Spring, just above Jamestown, and the General Assembly assumed the governing role, acting under the Parliament of England. Virginia was given liberal treatment, with considerable freedom in taxation and matters of government. The governors in this interval, elected by the assembly, were Richard Bennett, Edward Digges (an active supporter of the production of silk in Virginia), and Samuel Mathews. In 1660, on the death of Mathews, the assembly recalled Berkeley to the governor's office, an act that was approved by Charles II, who was restored to the English throne in that year. The decade passed quietly for the colony, although, in the years that followed, it had occasion to remember the liberal control that it had enjoyed. It had witnessed an increased wave of immigration that brought some of those who were fleeing from England, and this more than offset the loss of the Puritans whom Berkeley had forced out of the colony prior to 1650.

In matters of religion, Virginia continued loyal to the Church of England, although there was considerable freedom for the individual. The Puritans found it uncomfortable to remain, however, and two Quaker preachers, William Cole and George Wilson, soon found themselves in prison at Jamestown. Writing "From that dirty dungeon in Jamestown," in 1662, they described the prison as a place ". . . where we have not the benefit to do what nature requireth, nor so much as air, to blow in at a window, but close made up with brick and lime . . ." Lord Baltimore (George Calvert) did not find the colony hospitable when he visited Jamestown with his family in 1629, for, being a Roman Catholic, he could not take the Oath of Allegiance and Supremacy which denied the authority of the Pope.

BACON'S REBELLION, 1676—77. Bacon's Rebellion, one of the most dramatic episodes in the history of the English colonies, stands out as a highlight in 17th-century Virginia. It broke in spectacular fashion and is often hailed as a forerunner of the Revolution. It constituted the only serious civil disturbance experienced by Virginia during its entire life as a British colony. It occupies a prominent spot in the annals of the times, and in any chronicle of Jamestown its significance can be multiplied many times, for a number of its stirring events took place at the seat of government and resulted in excessive physical destruction in the town.

The rebellion had its origin in Indian frontier difficulties and a royal Governor (Sir William Berkeley) who, possibly as a result of his involvement in the Indian trade, had become somewhat dictatorial, tyrannical, and a firm advocate of the status quo. The leader for the exposed frontiersmen and the generally disgruntled Virginians came in the person of Nathaniel Bacon, a young man of good birth, training, and education who had come to Virginia in 1674. A distant kinsman of Lord Chancellor Francis Bacon and a relative of another Nathaniel Bacon, who was a leading citizen of Virginia, he soon became established as a first-rate planter at Curles, in Henrico County, and was admitted to the Governor's Council not long after his arrival.

Considerable underlying discontent had been aroused in Virginia by the low prices for tobacco, the cumulative effects of the Navigation Acts, high taxes, and autocratic rule by Berkeley, whose loyal supporters permeated the government structure and had not allowed an election of burgesses for 15 years. The spark came from the depredations of the Susquehanna Indians who were being forced south by the powerful Iroquois. They made attacks all along the Virginia frontier. Berkeley ordered a counterattack, but cancelled it in favor of maintaining a system of forts along the edge of the western settlements. In March 1676, the Assembly at Jamestown made plans for new forts; this measure, however, was both time-consuming and ineffective. Among the leaders who assembled at the falls of the James for consultation regarding the Indian menace was the young Nathaniel Bacon. William Byrd I was there, too, and, even though he was the officer who had been named to guard the frontier, Bacon was placed in command of the men sent to attack the enemy Indians. A messenger left to request a commission for him from the governor. Berkeley replied that he would discuss the matter with his Council. Bacon then set out with his men to collect allies from among the friendly Indians. While Bacon was on the march he received word from Berkeley ordering him to return or be declared a rebel. Bacon did not turn back but continued into the wilderness in search of the enemy. Action came at Occaneechee Island. Bacon returned with captives and was hailed as a hero by those who had heard of his exploits.

Governor Berkeley realized that the situation was becoming critical and that he could lose control of his government. Prompt action was necessary. He dissolved the House of Burgesses and ordered a new election. The result was that many of his loyal adherents were replaced by representatives, some of whom were unfriendly, even hostile, to him. The new assembly convened in the statehouse at "James Citty" on June 5, 1676, and among the burgesses was the defiant Bacon who had been returned by the voters of Henrico. An announced rebel and not yet formally removed from the council, it is doubtful that he was eligible for his seat, yet he determined to go to Jamestown and present his credentials.

He boarded his sloop, accompanied by about 40 supporters, and sailed down the James. When near Jamestown he sent ahead to inquire whether he would be allowed to enter the town in peace. A shot from a cannon in the fort gave the negative answer. Despite this, Bacon secretly went ashore at night to confer with two of his friends then living in Jamestown—William Drummond, a former governor in Carolina, and Richard Lawrence, a former Oxford student. Later that night he returned to his boat and started, back up the James, but was taken by an officer whom Berkeley had sent out to apprehend him. A dramatic scene followed at Jamestown.

Bacon was brought before the governor, paroled, and restored to the council. Berkeley knew that his opponent had the upper hand and that the House of Burgesses, then in session, was against him. Bacon seemingly could have remained in the capital and personally directed a full program of economic and political reform. This evidently was not his aim. He demanded a commission to go against the Indians, and, when Berkeley delayed, he disappeared from Jamestown, later saying that his person was in danger, although this appears unlikely. Bacon now entered a course from which he could not turn back. With a sizable group of supporters, on June 23, he returned again to Jamestown. He crossed the isthmus ". . . there le[a]veing a party to secure the passage, then marched into Towne, . . . [sent] partyes to the ferry, River & fort, & . . . [drew] his forces against the state house." In the face of this show of force, the governor gave him a commission, and the burgesses passed measures designed to correct many old abuses. Among the new laws was one establishing the bounds of Jamestown to include the entire island and giving the residents within these bounds the right, for the first time, to make their own local ordinances.

By this time Bacon and his men were arrayed solidly against both governor and royal government. The issue was defeat or independence for Virginia, but Virginia was not yet ready and did not elect to face the issue. Bacon, it seems, wanted extreme measures, and there is evidence to indicate that he visualized the formation of an American Republic. Yet when Bacon established himself as the opponent of royal government in Virginia and subordinated his role as supporter of the frontier settlers against misrule, he lost popular support. Had he lived and succeeded in arms, it is questionable that the people would have backed him, for they had not shown much disposition to defy royal authority. The discontent at this time was not so much against that authority as against the misuse of it by Sir William Berkeley.

The issues having been drawn, Bacon pursued his course to the bitter end. He returned to Henrico. When about to move a second time against the Indians, news came that Berkeley was attempting to raise troops in Gloucester County. Consequently, it was to Gloucester that Bacon first moved, only to find that his opponent had withdrawn to Accomac, on the Eastern Shore of Virginia. On August 1, at Middle Plantation (later Williamsburg), Bacon sought to administer his oath of loyalty and to announce his "Declaration of the People" to those assembled there at his summons. His next move was against the Pamunkey Indians. Then it seemed necessary that he move again on Berkeley who now had returned to Jamestown.

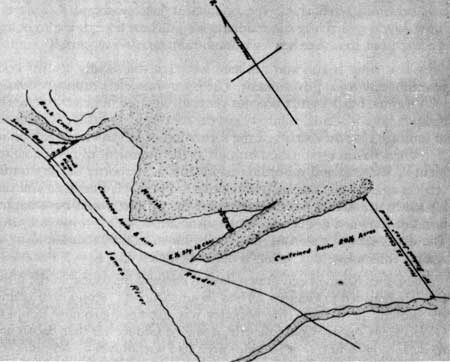

A prepared drawing of the plat of a survey made

for William Sherwood at Jamestown in 1680. "Roades" indicates the course

of the "Greate Road" that connected the town with the mainland. On the

left the isthmus that joined the "island" to Glasshouse Point is

shown.

On September 13, 1676, he drew up his "few weake and Tyr'd [tired]" men in the "Green Spring Old Field," just above Jamestown, and posted lookouts on Glasshouse Point. Then he ordered the construction of a trench across the island end of the isthmus. A raiding party advanced as far as the palisade, near the edge of Jamestown proper. Berkeley ordered several ships brought up as close to the shore as possible. Their guns and the small arms of the men along the palisades opened fire against Bacon, but proved ineffective in routing him from his entrenchments. On September 15, Berkeley organized a sally, "with horse and foote in the Van," which retreated under hot fire from Bacon's entrenchments. At this point Berkeley's force lost heart, while his opponent's spirit reached a new high. In any event, after a week of siege, the governor felt compelled to withdraw from Jamestown. This he did, by boat, with many of his supporters. This was the high point of Bacon's fortune in arms, and a costly one. Seemingly, it was during the fatiguing siege, which came "in a wett Season," that he contracted the illness that caused his death and brought an abrupt end to the rebellion.

Following Berkeley's withdrawal, Bacon and his tired force marched into Jamestown for rest. Wholesale destruction followed. As a contemporary put it, "Here resting a few daies they concerted the burning of the town, wherein Mr. Laurence [Richard Lawrence] and Mr. [William] Drummond owning the two best houses save one, set fire each to his own house, which example the souldiers following laid the whole town (with church and State house) in ashes...." It is known from the records that the destruction was systematic and that the town suffered heavily from the burning. Among those losing homes and possessions of high value were Col. Thomas Swann, Maj. Theophilus Hone "high sheriff of Jamestown," William Sherwood, and Mr. James "orphan," the last to the value of £1,000. It was estimated that total losses reached a value of 1,500,000 pounds of tobacco. Again the idea was advanced to move the seat of government from Jamestown to some more desirable location. A little later, Tindall's (now Gloucester) Point, on the York, was given preferential consideration by the assembly as a fit location. The move was not made, however, and the capital remained at James town for another quarter of a century.

From Jamestown, Berkeley moved once more to the Eastern Shore. Bacon, whose men pillaged Green Spring (Berkeley's home on the mainland, just above Jamestown) on the way, marched to Gloucester, where he became ill and died on October 26, 1676. The rebellion, now without a real leader, quickly collapsed. Joseph Ingram, successor to Bacon, and Gregory Wakelett, cavalry leader in Gloucester County, surrendered in January 1677; Lawrence disappeared in the Chickahominy marshes; and Drummond was promptly hanged. Berkeley moved with haste to silence his opponents, making ready use of the death sentence.

Accommodations for the conduct of government were now wholly inadequate at Jamestown. Consequently, Berkeley called the assembly to meet at Green Spring, which functioned for a time almost as the temporary capital. In February 1677, the commissioners who were sent to investigate Bacon's Rebellion arrived in Virginia. With them came about 1,000 troops who encamped at Jamestown for the remainder of the winter and ensuing spring. The commissioners, among them Col. Herbert Jeffreys, the next governor, finding so much ruin and desolation at Jamestown, made their headquarters in the home of Col. Thomas Swann across the James from the capital town. Berkeley left for England in May, and Jeffreys took control in Virginia. It was not until March 1679, however, that definite action (following a recommendation of the investigating commissioners) was taken for the restoration of Jamestown. Then it was ordered, in England, that the town be rebuilt and made the metropolis of Virginia "as the most ancient and convenient place."

A section from the "Plan du Terrein a la Rive Gauche de la Riviere

de James vis-a-vis JamesTown en Virginie ..." done by Colonel

Desandronins, of the French Army, in 1781.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |