|

FORT LARAMIE National Historic Site |

|

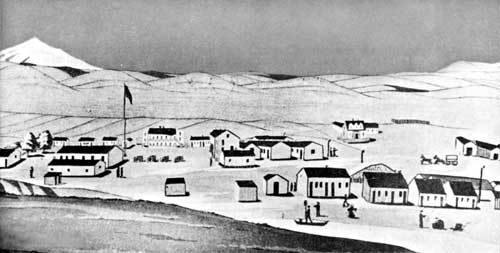

Fort Laramie in 1863. Note "Old Bedlam" to the

right of the flagpole

From a sketch in the University of Wyoming Archives by Bugler C.

Moellman, 11th Ohio Volunteer Cavalry.

The Civil War and the Uprising of the Plains Indians

The outbreak of the Civil War led to the reduction of garrisons at all outposts. This, coupled with a bloody uprising of the Sioux in Minnesota in 1862, inspired the Plains Indians, nursing many grievances, to go on the warpath. In the spring of 1862, many stage stations along the Platte route were raided and burned, To meet this threat, volunteer cavalry from Utah rushed east to the South Pass area, and the Eleventh Ohio Volunteer Cavalry under Col. Wm. O. Collins was ordered west to Fort Laramie. These raids also prompted the moving of the overland mail and stage route south to the Overland Trail and the establishment of Fort Halleck 120 miles to the southwest. During this period, troops at Fort Laramie continued to protect the vital telegraph line through South Pass and a still considerable volume of travelers, principally to Utah.

The next winter was fairly peaceful at Fort Laramie, and of social life at the post young Caspar Collins wrote to his mother: "They make the soldiers wear white gloves at this post, and they cut around very fashionably. A good many of the regulars are married and have their wives and families with them." He also indicated that they had a circulating library, a band, amateur theatricals, and an occasional ball. However, the dangers of the frontier were ever present, and, later that winter, troops en route from Fort Laramie to Fort Halleck encountered weather so severe that several were frozen to death.

Indians continued to steal horses from the overland mail stations, freighters, and ranchers; and incidents provoked by both whites and Indians piled up until the whole region was in a state of alarm. Efforts were made to call the Indians into the forts to treat for peace, but with little success.

At this time the difficulty of detecting the movements of Indian war parties was demonstrated at Fort Laramie. Returning from a 3-day scout, without finding a sign of hostile Indians, a large detachment of troops unsaddled their horses and let them roll on the parade grounds. Suddenly, at midday, a daring party of 30 warriors dashed through the fort, drove the horses off to the north and escaped, with all but the poorest animals, despite a 48-hour pursuit. The fort's commander, Major Wood, was described by his adjutant as "the maddest man I ever saw."

Later in 1864, after another attempt to make peace with the northern Indians had failed, Gen. R. B. Mitchell ordered the strengthening of the defenses along the road to South Pass. Several former stage and pony express stations were strengthened and garrisoned. Fort Sedgwick, near Julesburg, and Fort Mitchell, at Scottsbluff, were among those established. Fort Laramie became headquarters of a district extending from South Pass east to Mud Springs Station. Meanwhile, Indian raids along the South Platte River virtually cut off Denver from the east for 6 weeks.

Continuing efforts to seek peace with the Indians were made unsuccessful by the Sand Creek Massacre in November 1864, which united the southern bands of Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapahoe on the warpath, Early in January 1865, they raided Julesburg, sacking the station, carrying off great quantities of foodstuffs, and almost succeeding in destroying the garrison of Fort Sedgwick. Efforts to burn out the Indians by setting a 300-mile-wide prairie fire brought them swarming back to the attack, destroying the South Platte road stations and miles of telegraph line, sacking and burning Julesburg a second time, and driving off great herds of livestock. While troops from Fort Laramie arrived at Mud Springs Station in time to fight off the Indians there, all efforts by troops from Fort Laramie and the east failed to prevent the Indians from escaping with their booty across the North Platte, near Ash Hollow.

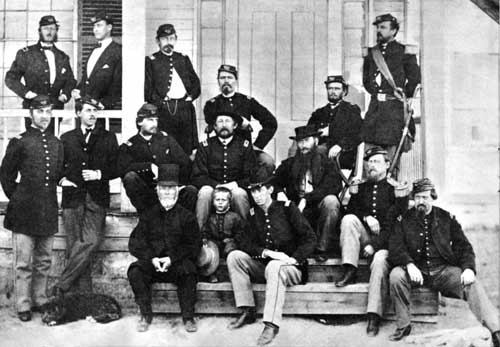

Group on the porch of "Old Bedlam" in 1864.

Courtesy Newberry Library.

Termination of the Civil War in April 1865 released many troops for service against the Indians, and plans were laid for extensive punitive expeditions, especially in the country to the north of the North Platte River.

In May, the fort's commander, Col. Thomas Moonlight, led 500 cavalrymen on a 450-mile foray into the Wind River Valley, but failed to find the Indians. Meanwhile, there were several raids on stations westward to South Pass. An effort to move a village of friendly Brules from Fort Laramie to Fort Kearny resulted in a fight at Horse Creek where Captain Fouts and four soldiers were killed as these Indians escaped to join the hostiles. In pursuing them, all of Colonel Moonlight's horses were stolen, and he returned to Fort Laramie in disgrace.

The major Indian raids of the summer centered on Platte Bridge Station, 130 miles above Fort Laramie, where late in July a large force of Indians wiped out a wagon train and killed 26 white men, including Lt. Caspar Collins who led a small party from the station in a valiant rescue effort.

In the meantime, a great campaign against the Indians, known as the Powder River Expedition, got under way with 2,500 men, directed by Gen. R. E. Connor. Of three columns planned to converge on the Indians in the Powder River country, the first, under Colonel Cole, started from Omaha, marched up the Loup River Valley, thence east of the Black Hills and on to the Powder River in Montana. The second, under Lieutenant Colonel Walker, left Fort Laramie, marched north along the west side of the Black Hills, and joined Colonel Cole's column as planned. The third, under General Connor, marched about 100 miles up the Platte from Fort Laramie, then north to the headwaters of Powder River where a small fort, Camp Connor, was established; thence, down the Powder River, where he destroyed the village and supplies of a large band of Arapahoes, but failed to meet the other two columns. The other commanders, lacking adequate supplies and proper knowledge of the country, lost most of their horses and mules in a September storm and, beset by fast-riding Indians, were forced to destroy the bulk of their heavy equipment. They were finally found and led to Camp Connor just in time to prevent heavy losses by starvation and possible destruction by Indians. The expedition straggled back to Fort Laramie, a failure.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Dec 9 2000 10:00:00 am PDT |