|

VICKSBURG National Military Park |

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The Vicksburg

Campaign: Grant Moves Against Vicksburg— and

Succeeds (continued)

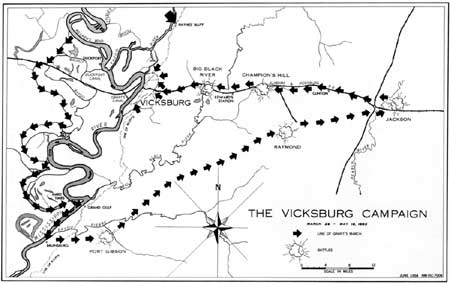

THE STRATEGY OF THE VICKSBURG CAMPAIGN. Grant's overall strategy, up to the capture of Grand Gulf, had been first to secure a base on the river below Vicksburg and then to cooperate with Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks in capturing Port Hudson. After this he planned to move the combined force against Vicksburg. Port Hudson, a Strong point on the Mississippi near Baton Rouge, was garrisoned by Confederate troops after Farragut's withdrawal the previous summer. At Grand Gulf, Grant learned that Bank's investment of Port Hudson would be delayed for some time. To follow his original plan would force postponement of the Vicksburg campaign for at least a month, giving Pemberton invaluable time to organize his defense and receive reinforcements. From this delay the Union Army could expect the addition of no more than 12,000 men. Grant now came to one of the most remarkable decisions of his military career.

Information had been received that a new Confederate force was being raised at Jackson, 45 miles east of Vicksburg. Against the advice of his senior officers, and contrary to orders from Washington, Grant resolved to cut himself off from his base of supply on the river, march quickly in between the two Confederate forces, and defeat each separately before they could join against him. Meanwhile, he would subsist his army from the land through which he marched. The plan was well conceived, for in marching to the northeast toward Edwards Station, on the railroad midway between Jackson and Vicksburg,

Grant's vulnerable left flank would be protected by the Big Black River. Moreover, his real objective—Vicksburg or Jackson—would not be revealed immediately and could be changed to meet events. Upon reaching the railroad, he could also sever Pemberton's communications with Jackson and the East. It was Grant's belief that, although the Confederate forces would be greater than his own, this advantage would be offset by their wide dispersal and by the speed and design of his march.

But this calculated risk was accompanied by grave dangers, of which Grant's lieutenants were acutely aware. It meant placing the Union Army deep in alien country behind the Confederate Army where the line of retreat could be broken and where the alternative to victory would not only be defeat but complete destruction. The situation was summed up in Sherman's protest, recorded by Grant, "that I was putting myself in a position voluntarily which an enemy would be glad to maneuver a year—or a long time—to get me."

The action into which Pemberton was drawn by the Union threat indicated the keenness of Grant's planning. The Confederate general believed that the farther Grant campaigned from the river the weaker his position would become and the more exposed his rear and flanks. Accordingly, Pemberton elected to remain on the defensive, keeping his army as a protective shield between Vicksburg and the Union Army and awaiting an opportunity to strike a decisive blow—a policy which permitted Grant to march inland unopposed.

With the arrival of Sherman's Corps from Milliken's Bend, Grant's preparations were complete and, on May 7, the Union Army marched out from Grand Gulf to the northeast. His widely separated columns moved out on a broad front concealing their objective. When assembled, Grant's Army numbered about 45,000 during the campaign. To oppose him, Pemberton had available about 50,000 troops, but these were scattered widely to protect important points. On the day of Grant's departure from Grand Gulf, Pemberton's defensive position was further complicated by orders from President Jefferson Davis that both Vicksburg and Port Hudson must be held at all cost. The Union Army, however, was already between Vicksburg and Port Hudson and would soon be between Vicksburg and Jackson.

In comparison with campaigns in the more thickly populated Eastern Theater, where a more extensive system of roads and railroads was utilized to provide the tremendous quantities of food and supplies necessary to sustain an army, the campaign of Grant's Western veterans ("reg'lar great big hellsnorters, same breed as ourselves," said a charitable "Johnny Reb") was a new type of warfare. The Union supply train largely consisted of a curious collection of stylish carriages, buggies, and lumbering farm wagons stacked high with ammunition boxes and drawn by whatever mules or horses could be found. (Grant began his Wilderness campaign in Virginia the following year requiring over 56,000 horses and mules for his 5,000 wagons and ambulances, artillery caissons, and cavalry.) Lacking transportation, food supplies were carried in the soldier's knapsack. Beef, poultry, and pork "requisitioned" from barn and smokehouse enabled the army which had cut loose from its base to live for 3 weeks on 5 days' rations.

A noted historian described this campaign: "The campaign was based on speed—speed, and light rations foraged off the country, and no baggage, nothing at the front but men and guns and ammunition, and no rear; no slackening of effort, no respite for the enemy until Vicksburg itself was invested and fell."

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |