|

VICKSBURG National Military Park |

|

The Surrender Site. The monument was erected and

inscribed by Union soldiers on spot where Grant and Pemberton

met.

The Siege of Vicksburg (continued)

THE SURRENDER OF VICKSBURG. By July, the Army of Vicksburg had held the line for 6 weeks, but its unyielding defense had been a costly one. Pemberton reported 10,000 of his men so debilitated by wounds and sickness as to be no longer able to man the works, and the list of ineffectives swelled daily from the twin afflictions of insufficient rations and the searching fire of Union sharpshooters. Each day the constricting Union line pushed closer against the Vicksburg defenses, and there were indications that Grant might soon launch another great assault which, even if repulsed, must certainly result in a severe toll of the garrison. (Grant had actually ordered a general assault for July 6, 2 days after the surrender.)

General Pemberton, faced with dwindling stores and no help from the outside, saw only two eventualities, "either to evacuate the city and cut my way out or to capitulate upon the best attainable terms." Contemplating the former possibility, he asked his division commanders on July 1 to report whether the physical condition of the troops would favor such a hazardous stroke. His lieutenants were unanimous in their replies that siege conditions had physically distressed so large a number of the defending army that an attempt to cut through the Union line would be disastrous. Pemberton's only alternative, then, was surrender.

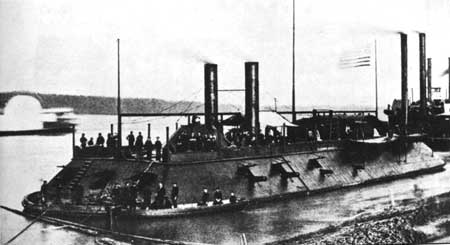

The Union ironclad gunboat Cairo, sunk by a Confederate "torpedo"

(mine) near Vicksburg.

From Photographic History of the Civil

War.

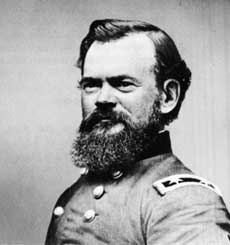

Maj. Gen. M. L. Smith, commanding the Confederate left at Vicksburg. Courtesy Library of Congress. |

Maj. Gen. James B. McPherson, commanding the Union XVII Corps. Courtesy Library of Congress. |

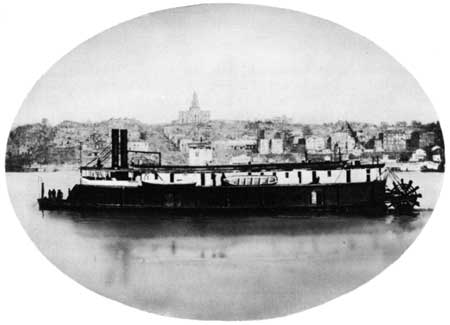

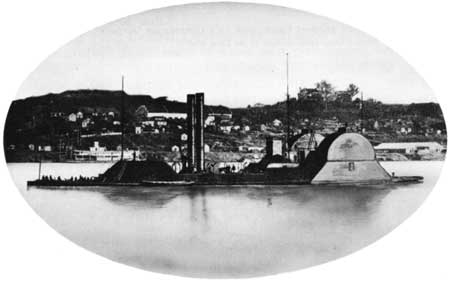

David and Goliath of the Union fleet, photographed

at Vicksburg after the surrender. Above: A patrol boat, the "tinclad"

Silver Lake. Below: The powerful ironclad ram Choctaw.

From

Photographic History of the Civil War.

Although not requested, Pemberton also received the verdict of his army in a message from an unknown private, signed "Many Soldiers." Taking pride in the gallant conduct of his fellow soldiers "in repulsing the enemy at every assault, and bearing with patient endurance all the privations and hardships," the writer requested his commanding general if he would "Just think of one small biscuit and one or two mouthfuls of bacon per day," concluding with the irrefutable logic of an enlisted man, "If you can't feed us, you had better surrender us, horrible as the idea is."

On July 3, white truce flags appeared along the center of the Confederate works. A few hours later, Grant and Pemberton met beneath an oak tree, on a slope between the lines, to arrange for the capitulation of Vicksburg and its army of 29,500. It had been 14 months since Farragut's warships had first engaged the Vicksburg batteries, 7 months since Grant's first expedition against the city, and 47 days since the beginning of the siege. On the morning of July 4, 1863, while Northern cities celebrated Independence Day, Vicksburg was formally surrendered. The Confederate troops marched out from their defenses and stacked their rifles, cartridge boxes, and flags before a hushed Union Army which witnessed the historic event without cheering—a testimonial of their respect for the courageous defenders of Vicksburg, whose line was never broken.

Into the city which had defied him for so long, and which nearly proved the graveyard rather than the springboard of his military career, rode General Grant. At the courthouse, where the Stars and Bars had floated in sight of the Union Army and Navy throughout the siege, he watched the national colors raised on the flagstaff, and then proceeded to the waterfront. With every vessel of the Navy sounding its whistle in celebration, he went aboard Porter's flagship to express gratitude for the work of the fleet.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |