|

OCMULGEE National Monument |

|

Excavation of Trading Post stockade. Darkened soil, indicating

position of log wall footing, emphasized to show gates (right half of

long wall, top of picture).

Ocmulgee Old Fields

After the Spanish exploration of Georgia in 1540, about 150 years elapsed before the Ocmulgee tribe of the Creek Nation settled at a place which we can now identify with reasonable certainty. This site in later years was known as Ocmulgee Old Fields, for the evidence of ancient cultivation can often be detected long after the signs of dwellings themselves have disappeared. Needless to say, this was the last Indian village of any importance to occupy the area now included in Ocmulgee National Monument.

The recognition of this village site was partly brought about by the intensive study of an interesting feature of Colonial construction disclosed early in the excavations. This consisted of a ditch about 1 foot wide by 2 in depth which outlined a curiously shaped area on the Macon Plateau some 200 yards north of the Great Temple Mound. Presumably the footing ditch for a palisade, it enclosed a space shaped like the gable end of a house with very low walls and a steep roof. The base side, facing northwest, was about 140 feet long and was interrupted at two points, suggesting a large central entrance gate with a smaller postern 18 feet to the left. Surrounding the enclosure on all but its long base side was a broad, shallow ditch which may have served as a moat. It might, though, have been used instead to improve the drainage of the stockade; for excavation showed that this lay close to old springs which had once issued from the adjacent high ground. Finally, the remains of a wide beaten trail from the northeast, worn a foot or two into the old land surface, were found to terminate before the entrance. This path had been traced at intervals across the plateau for about half a mile, and was picked up again beyond the enclosed area leading off down the hill toward the river.

Inside the stockade, rectangular blackened areas in the soil indicated what appeared to be the decayed remains of several log buildings, while mixed with the usual debris of an Indian village site were numerous articles of European manufacture. Both here and at other points, chiefly concentrated on the southwest corner of the Macon Plateau, excavation revealed iron axes, clay pipes, trade beads, brass and copper bells, knives, swords, bullets, flints, pistols, and muskets. All indications pointed to a large and thriving Indian community situated generally at the western edge of the old Master Farmer village site, and plentifully supplied with English trade materials. The fact that a small fortified structure existed in the midst of this community at once suggests the very trading post from which these goods were obtained.

Returning, now, to the Early Creeks, we left them sharing in the development of a distinctive material culture which characterized, with minor differences, a large portion of the Southeast. When we encounter their descendants on the site of Ocmulgee Old Fields, however, we find a mixture of old elements and new; and it is often difficult to say what part of the changes we observe was due to European contacts and what a normal continuation of the development which had gone before.

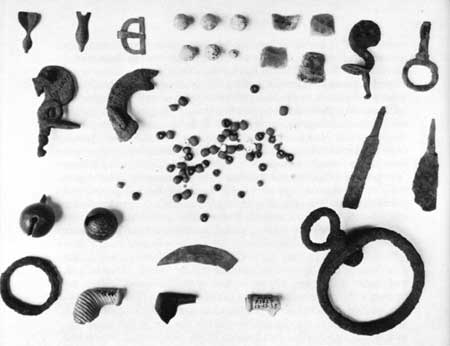

Beads, gun cocks, flints, lead shot, knives, pipes, brass bells, and

other trade goods show contact between Creeks and English.

The remains of this period were found thickly scattered about the Funeral Mound, between the latter and the Great Temple Mound, and about the area of the Trading Post itself, as we shall term the fortified enclosure, anticipating further discussion. They consisted of burials, pits filled with refuse, oval patterns of post molds indicating small house sites (although these were found only in and around the stockaded enclosure), and refuse of all sorts scattered about on the general level of the occupation. The burials were made both within the main village area and about the Funeral Mound, where the signs of habitation may have been destroyed by plowing. Usually the dead were buried in a flexed position shortly after death, and were not subsequently moved. This was true, also, of the earlier Lamar occupation, but in marked contrast to the Master Farmer custom of secondary burial, or the reinterment of bones already once buried or otherwise put away.

The pottery of these historic Creeks shows that they had finally given up the ancient habit of complicated stamping. This seems all the more curious when we reflect that their neighbors and enemies, the Cherokee, retained this idea, as previously mentioned, until they finally gave up pottery entirely. In place of it, the Creeks roughened many of their pots by brushing or stippling the surface, probably with a handful of small twigs or pine needles. The carinated bowl form was retained, however, along with deeper jars and other more common shapes of former times; and on its shoulder appeared a weak, thin incising, often hardly more than a series of crude scratches. Still, the interlocking scroll seems to have continued as one of the basic design ideas; but it was crudely executed, as were the hatched elements of parallel lines which were no longer carefully integrated with the re mainder of the design. One gains the feeling that the potter was striving for the same general effect, but was no longer interested in achieving the precision of pattern and boldness of line on which that effect originally depended. The lower parts of these bowls are now smooth, and many vessels are made without either decoration or roughening.

Creek pottery continued some of the more characteristic older

shapes, but the decoration was only a rough imitation of earlier designs.

Other artifacts suggest the increasing reliance on European goods supplied by the traders, which we know had already begun to destroy the rude but effective and self-sufficient culture of the Indians. A highly prized musket cost a man 25 deer skins; but once he had it, with bullets at 40 to the skin and powder 1 skin to the pound, he could kill more deer and would have little need to make arrow heads of flint. Another 4 skins would purchase an ax, 4 more a hoe; and again he had better, more lasting tools without the work of making them and constantly replacing them. Small wonder that stone tools and weapons become less frequent, and that flint chipping itself, within a few generations, had become a lost art.

While the Trading Post site has not yet been studied in detail, one gets the impression that stone tools are actually less numerous. Projectile points are mostly of small size, often very narrow triangles less than an inch in length. European materials like gun flints and bottle glass are used for scrapers. Glass trade beads are mixed with those made from the central core of the big marine whelk, commonly called "conch." Sheet copper is used for decorative cuff-like arm bands; frequently it is rolled into small cone-shaped janglers which were probably sewn to clothing in clusters to replace the old deer hoof rattles.

The Indian trade was the most effective weapon of the English in their contest with Spain and France for control of the southern frontier. Indirect evidence points to the establishment of a trading post in this vicinity about 1690 by the Charleston traders. Apparently lured by the prospect of English goods, a number of the principal Creek villages had moved about this time from the Chattahoochee, close to the Spanish settlements in west Florida, to the Altamaha and its western fork, the Ocmulgee. No direct reference to the position of the Ocmulgee town during this period has yet been found, though in 1675 and again after 1717 it was reported on the Chattahoochee. Nevertheless, the Ocmulgee are listed among Creek towns in this vicinity, and the river appears to be called by this name as early as 1704—5.

Early maps show the site of Macon to be occupied by the Hitchiti, a tribe of the Creek nation whose speech was older in Georgia than the Muskogean of the true Creeks. The Ocmulgee also spoke Hitchiti, and a Creek legend, recorded much later, states that the Hitchiti were the "first to settle at the site of Okmulgi town, an ancient capital of the Creek confederacy." Legend also named the Ocmulgee fields as the first town where the Creeks "sat down . . . or established themselves, after their emigration from the west." This identification, made at a time when the Old Fields were still in Creek territory, leaves little doubt that the Ocmulgee tribe itself had once lived here. The further evidence of a stockade erected here in a pattern then common to Colonial fortifications in the Southeast, plus the quantities of trade material in the village area, make it reasonably certain that this was another center of the little recorded trading enterprise so important to England's success in the race for colonial territory.

While it cannot be considered evidence in identifying the site, two additional bits of historic detail add interest to the part it may have played in the important events of this period. In December 1703, Col. James Moore set out upon a mission for the Carolina Assembly to destroy the Apalachee Indian settlements in west Florida. These Indians lived in agricultural communities, close to the missions where they received their religious indoctrination from the Spanish. They supplied important provisions for both St. Augustine and Havana; and their area served as a base for Spanish efforts to win over the Creek Indians to the north and so enlarge their dominion. Moore took with him 50 volunteers from Charleston, and gathering 1,000 Creek warriors on the Ocmulgee, set off southward for Florida. The raid proved highly successful and, with others like it over the following 2 years, dealt a devastating blow to Spanish colonial aims. By 1706, most of the Indian population of the area had been killed, driven away, or captured. Carolina was secure from inland attack, and Spain's efforts to enlarge her hold in the Southeast were at an end for all time.

Creek warriors join the Carolina volunteers at Ocmulgee for the

start of Moore's raid, 1703.

Returning now to Ocmulgee, we note that as late as 1828 a map of this region shows "Moore's Trail" running down the west bank of the river from a point about 2 miles below Macon. It is not hard, then, to imagine the former governor of the colony setting off on that bold adventure. A shouting horde of excited Creek warriors assembles near the trader's store. Moore watches as they fall in behind his sturdy band of Englishmen, and the line files past the high walls of the stockade. Following the Lower Patch down the hill, they march in the very shadow of that imposing relic of former days, the Great Temple Mound. Then a little distance clown the river they reach the fording place; and crossing it, are lost to sight as they enter the woods and take up the trail to the south.

This episode, however, was merely the beginning of the Indian's uphappy involvement in the rivalries of European nations and of the destruction of his own culture through his very eagerness to obtain the wonderful products of those nations. More and more the trader's goods were to become a necessity to him rather than a luxury. His life shifted from that of a village farmer to that of a hunter who left his village for months at a time in search of the deer skins on which the new barter economy was based. The women folk, of course, stayed home and tended the fields; but the old ways were steadily breaking down. Moundbuilding had been given up even before the coming of the English. With the barter economy, the religious festivals connected with the farming calendar were also abandoned during the prolonged hunting season. Only the great summer harvest festival, the "husk," or "poskita," remained as the central element of Creek religion. Finally, after the deer had been largely hunted out and the market for skins had almost dried up, the Indian became at last a log cabin farmer, exploited, but otherwise much like any other resident of the frontier.

Two scenes in the story of the Indians at Ocmulgee remain to be described. All along the Atlantic seaboard the red man awakened at last to his peril: the land hunger of the foreigners was insatiable, and in it lay a threat to his very existence. If lie could only have brought himself to forget old rivalries and have joined his ancient enemies in the common cause, perhaps they could have driven out the intruder before it became too late. Sooner or later bloody uprisings took place in most sections of the country, but the end was always the same. The old habits were too strong; cooperation could not replace hostility overnight; the Indian could not make the needed sacrifice though his life was at stake.

The Southeastern uprising was called the Yamassee War in which many of the shattered tribes of Georgia and Alabama took part. There can be little doubt that the Creeks, under the able command of their leader, Brim, were the principal actors. Under his guidance, they had at first helped the English against the better entrenched Spaniard, but now it was the Englishman himself who posed the chief threat and who must be driven out at any cost. The scheme was well planned—and came within a hair's breadth of success. It depended on winning over the Cherokee, who from the first had befriended the Charleston colonists; and to do this Brim took the unprecedented step of sending emissaries to his old enemy. If they had agreed to forget old hatreds, the Indians could easily have massed the strength to drive the colonists into the sea. Instead, the Cherokee council voted to stand by their old friends; and the announcement of their decision was the slaughter of the Creek emissaries.

Nevertheless, the others decided to carry on without them. Their first act in 1715 was to kill off the traders scattered about the Creek Nation and to attack outlying settlements. Here, we can be sure, the trader to Ocmulgee lost his life, unless by good fortune he happened to have gone to Charleston to lay in supplies. In any case, the existence of the store must have terminated. Little more was accomplished, however; the Creek design had failed, and in 1717 the war came to an end. Ocmulgee and the other towns along the river were then too close to the English settlements at Augusta, and the Indians moved their villages back to the Chattahoochee.

About 1773 we have a vivid description of the mounds and of extensive old fields along the river, but there is no mention of Indians living anywhere near the site. It is then, however, that we first learn of the high regard of the Creeks for this spot; for here it was, according to tradition, that the confederacy was first established. In 1805 the Creeks ceded to the United States most of the lands bordering the Ocmulgee River on the east; but in this treaty they specifically reserved for them selves about 15 square miles encompassing the site of Ocmulgee Old Fields, though allowing the Government the right to erect a military post or trading house thereon. In 1806, Fort Hawkins was built a short way to the north of the Plateau on high ground commanding the river. It was designed as a frontier outpost and factory, or trading house; and it served this end until 1817, when it was moved west to Fort Mitchell in Alabama Territory to keep up with the movement of the frontier. Once more the Indians gathered here in 1819 to receive the annual payment for their lands east of the Ocmulgee; but the city of Macon was founded only 4 years later, and in 1828 Ocmulgee Old Fields was sold to the public.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |