|

CHALMETTE National Historical Park |

|

Jacques Philippe Villeré, Major General in

the Louisiana Militia and owner of the plantation on which part of the

action at Chalmette took place in 1814—15.

Courtesy,

Louisiana State Museum.

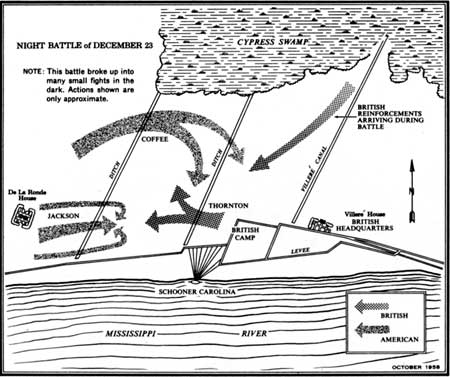

The Night Battle of December 23

After getting control of Lake Borgne, the next British problem—finding a way to New Orleans—was solved by Capt. R. Spencer of the Royal Navy and Lt. John Peddie of the Quartermaster Department. Disguised as fishermen, these officers reached the Mississippi and found that small boats could go through the bayous most of the way to the great river. They had penetrated by way of Bayou Bienvenue and found no sign of American preparation. The British spies had seemingly found the only unguarded bayou. Their commanders decided to advance along this route.

Before reaching the mouth of Bayou Bienvenue, however, British seamen and soldiers were driven to tremendous exertions and suffered great hardships. To cross the shallow Lake Borgne, the troops on the heavy ships had to load into vessels that drew less water. They then went to Pea Island, near the mouth of Pearl River, for regrouping. The shortage of shallow-draft boats made the British divide their land force into two brigades. The Light Brigade, composed of the 85th and 95th Regiments, rocket troops, sappers, and miners, with the 4th Regiment as support, formed the advance commanded by Col. William Thornton. The 2d Brigade, under Col. Arthur Brooke, was made up of the 21st, 44th, and 93rd Regiments, with much of the artillery.

The plantation house of Maj. Gen. Jacques

Villeré was used by the British as headquarters from December 23,

1814, to January 19, 1815. This drawing shows the old house as it was

about 1860.

Photocopy by Dan Leyrer from Lossing's Pictorial

Field Book of the War of 1812.

From Pea Island the invaders went in open boats to the mouth of the bayou. Even the lighter boats sometimes grounded. Many sea men were at the oar for the greater part of 4 or 5 days. During these journeys, the British had no fires or warm food and they were exposed to drenching rains. Once, after a heavy rain, the skies cleared and the night became bitter cold. Ice formed before morning. Many of the West Indian Negroes, unused to such a climate, died of exposure.

Pushing on despite these hardships, the invaders captured the small American detachment at the mouth of Bayou Bienvenue about midnight of December 22, before other Americans could be warned of the attack. Joseph Ducros, a native of Louisiana, was among the captives. When questioned by Admiral Cochrane and Maj. Gen. John Keane, he told the British officers that there were 12,000 or 15,000 American soldiers in New Orleans and 5,000 more farther down the river. Cochrane and Keane were impressed, though not convinced, and continued to move forward cautiously.

The British advanced along the bayous—some in boats, and some marching along the banks—until they reached firm ground at the edge of the Villeré plantation. Late in the morning of the 23rd, they rushed the plantation house, where they surprised and captured a militia detachment. The British had scored a tremendous tactical advantage: they had reached, almost unopposed, a spot within 9 miles of their goal.

But their presence was soon made known. Maj. René Philippe Gabriel Villeré had escaped in a clatter of musketry, and other Americans had seen the invaders. That morning, Jackson had received a message from Col. Pierre Denis de La Ronde saying that the British fleet was in a position that suggested landing. The American commander had sent Majors Howell Tatum and A. L. Latour to reconnoiter. Before they came back, Augustin Rousseau galloped to headquarters on Royal Street with astounding news. He had barely delivered his message when others, including young Villeré, arrived muddy and nearly out of breath.

Maj. J. B. Plauche, commander of the Orleans

Battalion of Uniform Militia Companies. His battalion fought in the

Night Battle of December 23 and afterward held a section of the line on

the Rodriguez Canal.

From the portrait by Vaudehamp. Courtesy,

Louisiana Stare Museum.

According to an oft-repeated story, Jackson, still not well, was lying on a sofa in his headquarters about 1 o'clock in the afternoon when the news came that the enemy was in force only 9 miles below New Orleans. He jumped up from the sofa, and, "with an eye of fire and an emphatic blow on the table" cried:

"By the eternal, they shall not sleep on our soil."

Then, quickly becoming calm, Jackson called his aides, and said, "Gentlemen, the British are below. We must fight them tonight."

Jackson's decision to attack at once was as important as any ever made by a commander. The British could have entered New Orleans easily at this time, for there were no important forces or defensive works between them and the city.

Jackson's move was more than the impulse of a man who at last could attack an enemy hated since boyhood. The British troops were tired, his were fresh. He had the advantage of darkness and surprise. He hoped also that action would improve morale, especially of the civilian population.

When Jackson learned that the British had landed, Carroll's and Coffee's men were 4 or 5 miles above the city, Maj. J. B. Plauche's Battalion was at Fort St. John on Lake Pontchartrain, Daquin's Battalion of San Domingo Men of Color and the Louisiana Militia under Claiborne were on Gentilly Road, and the regulars were scattered about the city. The naval commander, Commodore Patterson, was also some distance away.

Orders to assemble brought quick action. The first troops arrived in the narrow streets of the Old French Quarter by midafternoon. Plauche's Battalion ran to the city (a feat which is commemorated yearly by a race from the old Spanish fort to Jackson Square). The Tennesseans under Carroll and Coffee arrived less than 2 hours after orders were issued.

Carroll and his men were ordered to join Governor Claiborne in case the landing at Villeré's was a feint. The others started about sunset on their way along the road toward the enemy. Col. Thomas Hinds' Dragoons, recent arrivals from Mississippi Territory, and Coffee's Brigade of mounted infantry formed the advance. They were followed by the Orleans Rifle Company under Capt. Thomas Beale, Jugeat's Choctaws, Daquin's Battalion, two pieces of artillery commanded by Lt. Samuel Spotts, the 7th Regular United States Infantry under Maj. Henry D. Peire, a detachment of United States Marines under Lieutenant F. B. Bellvue, the 44th Regular United States Infantry under Maj. Isaac L. Baker, and Plauche's Battalion. Altogether, some 2,000 men marched with Jackson along the Mississippi River in the winter twilight.

Meanwhile the schooner Carolina went to take position opposite the British encampment. Capt. John D. Henly commanded and Commodore Patterson was on board.

About 4 p. m. a reconnoitering party on land had clashed with a British outpost. This party returned without a good estimate of the enemy's numbers. They had picked up copies of a proclamation to the Creoles, however, telling them that if they remained quiet, their property and slaves would be respected. It was signed by Vice Admiral Cochrane and General Keane.

At nightfall, Jackson's forces reached the spot where the De La Ronde Oaks stand today. (These trees, probably planted about 1820 are often miscalled "Pakenham Oaks" or "Versailles Oaks.")

There the little army divided. General Coffee commanded one division, consisting of part of his brigade of Tennessee mounted infantry, the Orleans Rifle Company, and the Mississippi Dragoons. The other division, under command of Jackson himself, consisted of the artillery on the road along the levee, then, on a line almost perpendicular to the river, the marines, the 7th and 44th Infantry, the battalions of Plauche and Daquin, and the Choctaws. By then it was dark, except for the light of a dim moon.

De La Ronde Ruins. The remains of what was once

the finest mansion in the Chalmette vicinity. The British used it as a

hospital in 1814—15.

Photograph by Kay Roush.

Coffee, guided by Colonel de La Ronde, a plantation owner familiar with the terrain, was to circle to the left and attack from that side. Every man was to keep quiet until the Carolina's opening volley—the signal for the battle to begin.

While all this was happening, such of the British as were already encamped had been enjoying food and wine from the plantations, and getting their first rest in several days. Campfires showed plainly the position of those between Villeré's house, and the levee. Outposts and sentinels had been posted, including a detachment not far from Jackson's army. Only part of the British land forces were there when the fighting began—about 1,680 men. Others were on the way.

A7 7:30 p. m., the Carolina's opening broadside hit the unsuspecting foe. Recovering from their consternation like the veterans they were, the British put their campfires out, and began to shoot at the schooner. Their muskets and rockets were of even less effect than their 3-pounders—the biggest guns they had. The noise of the battle was heard by their troops on Lake Borgne, and by the people in New Orleans. The British troops under the schooner's fire could only lay close to the levee or hide behind buildings, while they listened to the moans and shrieks of the wounded. They were so impressed by the volume of cannon fire that their commander mistakenly reported "two Gun-vessels" besides the Carolina.

For 10 minutes, "which seemed thirty," Jackson let the little ship carry on the fight alone. Then he ordered his division to advance. The accounts of what followed, on both sides, are confused and contradictory. In the darkness, troops in both armies became separated from each other, and the battle broke up into many small fights. Men were captured because they did not know where they were. Troops fired into other units of their own forces. Such things happened to both armies as the battle swayed back and forth.

The infantry under Jackson got off to a bad start, some advancing in column and others in line. A company of the 7th Infantry was the first to clash with the enemy. Its advancement with a discharge of musketry. The Americans drove the invaders back; the British were reinforced, and the two forces continued to shoot at each other in the dark. This action was typical of the battle.

Confused fighting and marching in the dark,

illuminated momentarily by flashes of gunfire—such was the battle

of December 23.

Photocopy by Dan Leyrer from Frost's Pictorial

Life of Andrew Jackson.

The main body of the 7th Infantry, coming on, engaged in a brisk fire, followed by the 44th Infantry, which also began to fire as the action became general. The artillery and marines advanced with the regulars. The two cannon were placed and began to fire in the direction of the enemy. Flashes from the Carolina, and later from Coffee's men showed other actions of the battle. In Jackson's Division, the militia apparently lagged at first and seems to have fired into the more advanced regulars. The British tried to turn the line by attacking the militia, but Plauche's and Daquin's Battalions returned the fire and drove them back.

Then larger units of the British 85th and 95th Regiments under Col. William Thornton came into the fight, and the Americans had to give ground. The two American fieldpieces were threatened. Jackson himself is said to have saved them. Reorganized somewhat, the Americans drove the enemy back again. The 93rd Highlanders arrived to reinforce the British. The Carolina ceased firing as a fog made all further action impossible.

This reproduction of W. A. C. Pape's painting,

"The Night Battle of New Orleans," depicts a scene during Jackson's

surprise attack on the British at the Villeré plantation on the

night of December 23, 1814. In the light cast by burning British

supplies, Jackson is seen arriving at the point where the capture of his

guns was being threatened in the general confusion of the night

fighting.

In the meantime, Coffee and his men had moved to the left to at tack the British flank. The Tennesseans dismounted and turned their horses loose because the canefields where they fought were cut by ditches. Coffee's men were almost in position when the Carolina opened fire. Then they advanced, firing rifles and muskets into the British camp. Experienced in Indian warfare, and accustomed to night battles, the frontiersmen drove the British back. Fighting as individuals, they cut their way through the British camp. "In the whole course of my military career I remember no scene at all resembling this," a British officer wrote later. "An American officer, whose sword I demanded, instead of giving it up . . . made a cut at my head." Friend and foe were confused in the dark.

British reinforcements from Lake Borgne arrived, and their army found a position behind an old levee. Coffee's men could not dislodge them, although these Tennesseans kept on shooting after Jackson's immediate command had ceased. Both wings of the American army withdrew to a place near the De La Ronde mansion and waited for daylight.

The Americans lost 24 killed, 115 wounded, and 74 missing. The British commander reported 46 killed, 167 wounded, and 64 missing. Among the prisoners taken by the Americans was Maj. Samuel Mitchell, who was supposed to have set fire to the Capitol in Washington.

New Orleans was saved for the time being. Although Jackson had not driven the enemy from American soil, the results were important. The invader's surprise had been met by a countersurprise. The British had been given a bad fright by the hitherto despised Americans. The invaders had been thrown off balance, and did not recover during this campaign. The Night Battle of December 23 went far toward making the British cautious, when they might still have captured their prize by moving fast.

It had been a close call. Jackson himself wrote that had the British arrived a few days sooner, or had the Americans failed to attack them in their first position, the invaders probably would have taken New Orleans.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |