|

CHALMETTE National Historical Park |

|

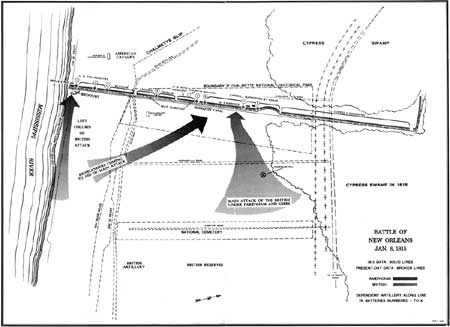

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The Battle of New Orleans, January 8, 1815

Jackson had about 4,000 men on the line on January 8. Pakenham had about 5,400 in his attacking force. Half of Jackson's men on the line had spent the night at the breastworks, taking turns occasionally. Their commander was awakened shortly after 1 a. m., and from then on was going up and down the line, inspecting, encouraging the men, and dictating orders.

THE OPPOSING FORCES*

|

British Invaders Infantry Regiments 4th (King's Own)7th (Royal Fusileers) 21st (Royal North British Fusiliers) 43rd (Monmouth Light Infantry) 44th (East Essex) 85th (Bucks Volunteers) 93rd (Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders) 95th (Rifle Corps; 6 companies) 1st & 2nd West Indian (colored) Staff 14th Dragoons dismounted Artillery, drivers, engineers, rocker troops, sappers & miners Sailors and marines from the fleet (Some of the English regiments already had long and glorious histories, and were to serve with distinction on many a later battlefield.) |

American Defenders 7th and 44th Regular United States Infantry Coffee's Tennessee Mounted Infantry Louisiana Militia, including Orleans Rifle Company (Beale's Rifles)Orleans Battalion of Uniform Companies Carabiniers Dragons à Pied Francs Chasseurs Louisiana Blues Baratarians Other Louisiana Militia in reserve Tennessee Militia Kentucky Militia Two battalions of Free Men of Color Detachment of United States Marines Company of Choctaw Indians Cavalry: Hinds' Mississippi Dragoons Attakapas DragoonsChauveau's Horse Volunteers Feliciana Troop of Horse Ogden's Cavalry |

* Reliable figures not available on the numbers of these troops. One authority is quoted as estimating that Jackson and Pakenham each had about 10,000 in all—others say 15,000 or 20,000.

American regulars and frontiersmen firing at the

British from behind the mud ram part during the battle of January

8.

One thing after another went wrong with British plans on the night of January 7—8. The banks of the freshly dug canal caved in before all the boats for the attack across the river got through. The 24 boats that made the passage were late starting and were carried by current farther downstream than expected. Consequently they were not ready when the main battle began.

Preparations did not start off well in front of Jackson's line either. Pakenham had divided the attacking force into 3 groups. General Gibbs, with 3 regiments, and 3 companies of another, was to attack near the cypress swamp, hitting the American line in the vicinity of Batteries 7 and 8. General Keane was to attack along the river with a smaller body of men. General Lambert was to remain in reserve with 2 regiments.

The 44th Regiment had been chosen to lead the predawn attack. They were to carry bundles of cane stalks (called fascines) to throw in the Rodriguez Canal and ladders for scaling the mud wall. In the darkness, regimental commander Lt. Col. Thomas Mullins led his men past the redoubt where the ladders and fascines were stored without picking them up. (After the battle, the British would blame Mullins for their defeat.) It is uncertain whether he or General Gibbs sent part of the regiment back for the ladders and fascines. In any case, the column was thrown into confusion and the attack delayed past the most favorable moment. Pakenham, it is said, dared not change his plans at the last moment because of taunts from Admiral Cochrane about the army's incapacity.

About daylight, a rocket shot up from the British forces near the woods, followed by another from their ranks near the river. These signals to attack were answered almost instantly by a shot from the American artillery. Gibbs' column gave three cheers and started forward in close order. American Batteries 6, 7, and 8 began to pour round shot and grape into the column. In spite of gaps torn by missiles from the artillery, the British veterans continued to advance in fairly good order until they came within musket range of the Tennessee and Kentucky troops. Small arms fire from 1,500 pieces added to that from the artillery soon broke the advancing column.

The defenders stood 3 and 4 deep behind the protective mud wall. An infantryman fired his gun, stepped down from the rampart to reload, and was instantly replaced by another. A witness wrote later of ". . . that constant rolling fire, whose tremendous noise resembled rattling peals of thunder." One surviving British officer said that the American line looked like a row of fiery furnaces.

After 25 minutes of this hail of lead, the attackers broke and ran. Though they were rallied by their officers, it was the same story over again. Only seasoned troops would have stood so long, and only such troops could have been rallied. Gibbs was mortally wounded trying to drive his soldiers forward. Pakenham soon met the same fate, dying on the way to the rear after being hit a second time. Many of the lower ranking officers were already dead or seriously wounded. Numbers of the rank and file had lain down on the field— the only way to escape the murderous fire.

Highlanders and other British forces storm the

American line and are repulsed with devastating

losses.

Keane, commanding the British near the river, saw Gibbs' plight and obliqued across the field with the kilted 93rd Highlanders. (Forty years later, this regiment was to be the "thin red line" at Balaclava.) According to legend, their commander, Col. Robert Dale, handed his watch and a letter to a surgeon, saying, "Give these to my wife. I shall die at the head of my regiment." On the Highlanders came, in spite of a volume of fire such as even these veterans had never known before. Their colonel was killed and Keane was seriously wounded. A few men reached the mud rampart, but they were all quickly killed or captured. Confusion and terror became panic.

The command of the column along the river had fallen to Col. Robert Rennie. Under protection of the fog, lasting longer there, Rennie stormed the American lines. Driving out defenders in hand-to-hand fighting, Rennie and some of his men seized the redoubt at the right of the American line. Then, mounting the breastwork, he called on the "Yankee Rascals" to cease firing, and cried, "The enemy's works are ours." But he barely said this when rifle fire smote him down. American muskets and cannon ended the British attack along the river as disastrously for the attackers as they had at the other end of the line.

Pakenham's last order was for Lambert to bring up the reserve, but, deciding that the battle was hopeless, General Lambert withdrew the army from the field. The infantry action had not lasted more than 2 hours.

The joy of Jackson and his men turned to consternation when they beheld the Americans across the river fleeing from the enemy. Although late in landing, Colonel Thornton's force had found little to oppose it along the west bank of the Mississippi. First to be reached was an outpost manned by militia, many of them tired and hungry and poorly armed. After firing a few volleys, the militia fled to an unfinished line that ended in an open field. There they formed a short distance from the other Americans manning the line. The entire force was under the command of Brig. Gen. David B. Morgan.

The strongest part of this line was along the river where Commodore Patterson had mounted several naval guns. These, firing across the river, had helped to repel the attacks on Jackson's line, including that which had just been defeated. The remainder of the line, according to one description, was only a waist-high wall of dirt behind a shallow ditch. Even this did not extend all the way to the swamp. There were also gaps between the various units defending it.

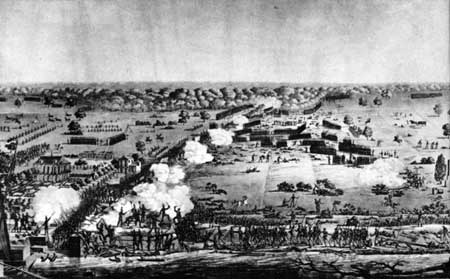

This unusual perspective drawing of the Battle of

New Orleans, January 8, 1815, was made in 1815 by Hyacinthe Laclotte, an

engineer in Jackson's army. The Mississippi River is seen in the

foreground. Just beyond is the American redoubt in front of the main

line. It is being stormed by British troops under Colonel Rennie.

Jackson's line can be traced from the river bank to the point where it

disappears in the heavily wooded swamp. Back of the American line, near

the river at the left, is the Macarty plantation house. Here Jackson had

his headquarters. The ruins of the Chalmette plantation buildings are at

lower right. Even the levee is shown, with British soldiers advancing on

either side, but few on top of it. Gibbs led the British troops near the

woods. Pakenham was mortally wounded while trying to rally the troops

massed in the center of the picture.

This reproduction is from a

copy of an engraving by P. L. Debucourt. Courtesy, Prints Division, New

York Public Library.

By attacking next to the swamp, and between the two groups of defenders, Thornton broke this line, in spite of some losses from cannon fire. The defenders fled after efforts of their officers to rally them were unsuccessful.

Thornton's plan included seizing the cannon mounted along the river. If Patterson had not succeeded in spiking his guns, the British might have raked the rear of the line on the Rodriguez Canal and undone the American victory. Even as it was, they were soon on their way to New Orleans with little to stop them.

Then came the order to withdraw. The army opposite Jackson had been shot to pieces so badly that the British victory across the river was of no use to them.

Estimates of British casualties on January 8 vary widely. One of their reports gives a total of nearly 2,000 killed, wounded, and missing. (According to the official regimental history, the 4th Regiment lost over 400 on this day—more than 3 times as many as they were to lose at Waterloo a few months later.) The official American estimate of the enemy's loss was 2,600. Others guessed 3,000 or more.

The defenders found it hard to believe that their own losses were only 7 killed and 6 wounded.

Rarely have first-rate soldiers been defeated in so one-sided a battle.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |