|

CHALMETTE National Historical Park |

|

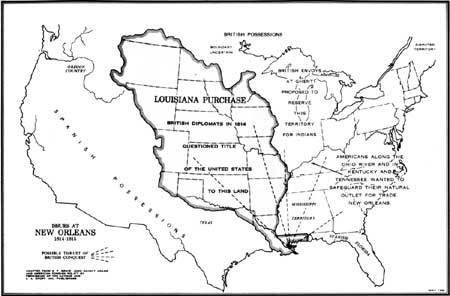

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

What the Victory Meant to the United

States

The Battle of New Orleans was fought between the signing and the ratification of the Treaty of Ghent, ending the War of 1812. It can not be stated whether the British, if they had won, would have insisted on changing the peace treaty. Partly because of the American victory in Louisiana, however, the treaty was promptly ratified by both sides.

Much of the significance of the Battle of New Orleans is found in its effect on political thinking. From its founding, many men doubted that the new United States would endure. Conservative Europeans pointed to many examples, from the failure of the Roman Republic to the excesses of the French Revolution, which seemed to prove that republics could not govern large territories. In the United States too, men often questioned whether the young nation would last. Even after the Constitution had been adopted, many regarded themselves as primarily citizens of their respective States. We have seen that news of the British defeat helped to end a secession movement in New England. Partly because of the victory's unifying effect, the United States endured as a republic. Its success belied the prophesies of the skeptics, and its form of government became a model for the new nations of Latin America.

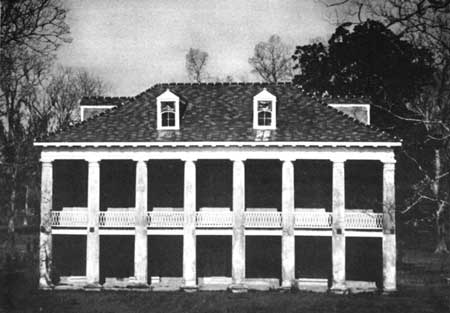

The René Beauregard House, traditionally

called "Bueno Retiro." The original structure was apparently built in

the early 1830's and probably later altered considerably in the 1850's

and 1860's. It is located in front of the American defense line of 1815.

This view shows the structure before it was rehabilitated as the visitor

center for the park.

Photograph by Kay Roush.

The victory meant much to the people of the United States as a nation. It helped them to forget earlier defeats in the War of 1812—such as Detroit, Niagara, and the burning of Washington—and it helped them to feel pride in their country as a whole. This national feeling was shown in the following years by the establishment of the Second Bank of the United States, protective tariffs, increased army appropriations, and acceptance of the nationalizing opinions of Chief Justice John Marshall.

Before 1815, American leaders had watched with anxiety every political and military move in Europe. After the New Orleans victory they stood on their own feet.

With other military events of those years, the New Orleans campaign cleared the way for a wave of migration and settlement along the Mississippi. The battles helped to advertise the West. Jackson's soldiers, coming and going, marked and built roads and trails, and made people better acquainted with water routes. More important possibly than all, was that European and Indian threats to the Mississippi River were now ended, and the outlet for Western products was open at last.

Finally, from the smoke and glory of New Orleans, Andrew Jackson emerged as a national hero. For the first time, a Westerner arose to challenge the power of the Eastern "aristocracy" which, until then, had dominated the national politics of the United States. Soon after the battle, he was mentioned for the Presidency. He became a candidate in 1824. Although Jackson received a plurality of popular votes in this election, he lost in the Electoral College in a four-cornered race. His winning of the next election, in 1828, was hailed as a triumph of the people.

This is not the place to tell the story of Andrew Jackson's 8 years in the White House. His outstanding characteristics as President were his devotion to the Union, his faith in the plain people, and his courage. He was as unafraid of any opposition in politics as he had been on the battlefield.

Out of office, the old warrior became an "Elder Statesman" and adviser to Presidents. As such, he was influential in the annexation of Texas. In 1840, he visited New Orleans for the 25th anniversary of the battle. At that time he laid the cornerstone of the monument to him in downtown New Orleans' Jackson Square, as the old Place D'Armes is now called.

In 1843, Congress refunded with interest the fine that Andrew Jackson had paid in New Orleans in 1815.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |