|

ANTIETAM National Military Site |

|

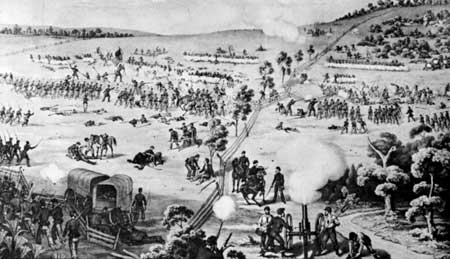

The Battle of South Mountain.

From

lithograph by Endicott. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

Fighting for Time

at South Mountain

By September 12, Lee had begun to worry. Stuart's scouts had reported the Federal approach to Frederick. McClellan was moving too fast. Next evening things looked worse. Jackson had not yet captured Harpers Ferry, and already McClellan's forward troops were pushing Stuart back toward the South Mountain gaps. Delay at Harpers Ferry made these passes through South Mountain the key to the situation. They must be defended.

South Mountain is the watershed between the Middletown and Cumberland Valleys. The Frederick-Hagerstown road leads through Middletown, then goes over South Mountain at Turner's Gap. At the eastern base of the mountain, the old road to Sharpsburg turned south from the main road and passed through Fox's Gap, a mile south of Turner's Gap. Four miles farther south is Crampton's Gap, reached by another road from Middletown.

On the night of September 13, Lee ordered all available forces to defend these three passes. D. H. Hill, with Longstreet coming to his aid, covered Turner's and Fox's Gaps. McLaws sent part of his force back from Maryland Heights to hold Crampton's Gap.

Next morning the thin-stretched Confederate defenders saw McClellan's powerful columns marching across Middletown Valley. Up the roads to the gaps they came—ponderous and inexorable. The right wing of McClellan's army under Maj. Gen. Ambrose Burnside assaulted Turner's and Fox's Gaps. The left wing under Maj. Gen. William Franklin struck through Crampton's Gap. By nightfall, September 14, the superior Federal forces had broken through at Crampton's Gap; and Burnside's men were close to victory at the northern passes. The way to the valley was open.

By his stubborn defense at South Mountain, Lee had gained a day. But was it enough? McClellan's speed and shrewd pursuit, together with Jackson's inability to meet the demanding schedule set forth in Special Order 191, had fallen upon Lee with all the weight of a strategic surprise. No longer could he command events, pick his own objectives, and make the Federal army conform to his moves. Rather, the decision at South Mountain had snatched the initiative away from Lee. His plan for an offensive foray into Pennsylvania was wrecked. Now it was a question of saving his army.

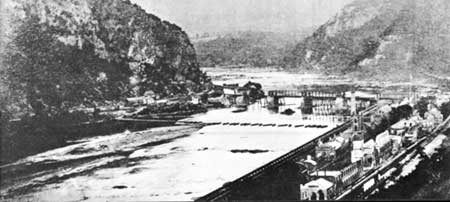

Harpers Ferry looking east toward confluence of

Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers. Ruins of armory in right foreground.

Maryland Heights, left; Loudoun Heights, right.

From 1862 photograph by Brady. Courtesy, Library of Congress.

The first step was to call off the attack on Harpers Ferry. At 8 p.m., September 14, Lee sent a dispatch to McLaws stating,

The day has gone against us and this army will go by Sharpsburg and cross the river. It is necessary for you to abandon your position tonight. . . . Send forward officers to explore the way, ascertain the best crossing of the Potomac, and if you can find and between you and Shepherdstown leave Shepherdstown Ford for this command." Jackson was ordered ". . . to take position at Shepherdstown to cover Lee's crossing into Virginia."

But then came a message from Jackson: Harpers Ferry was about to fall. Perhaps there was still hope. If Jackson could capture Harpers Ferry early the next day, the army could reunite at Sharpsburg. Good defensive ground was there; a victory over McClellan might enable Lee to continue his campaign of maneuver; and should disaster threaten, the fords of the Potomac were nearby.

At 11:15 p.m., Lee countermanded his earlier order; the attack on Harpers Ferry was to proceed. Shortly after, Longstreet's divisions began to march through the night toward Sharpsburg.

|

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Mar 4 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |