|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

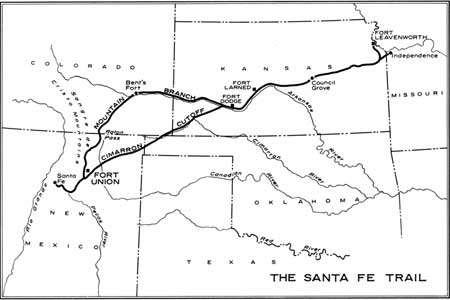

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

The Santa Fe Trail

Capt. Zebulon M. Pike went west in 1806 to explore the Rocky Mountains, part of which the United States now owned as a result of the Louisiana Purchase. Wandering through the mountains in midwinter, Pike and his handful of men camped in January 1807 on the headwaters of the Rio Grande, in Colorado's San Luis Valley. They built a stockade and hoisted the American flag—over soil belonging to His Catholic Majesty, the King of Spain. Spanish dragoons hauled the American officer before José Real Alencaster, Governor of the Province of New Mexico, in the Royal Capital of Santa Fe. Here and in Chihuahua, to the south, Pike had several bad months. The Spanish finally freed him in June 1807, and he went home to write of his adventures.

The Pike journals, published in 1810, gave Americans their first glimpse of the people and way of life behind the wall of secrecy Spain had erected on the frontiers of New Mexico. Missourians were quick to detect commercial opportunities in overland trade with Spanish settlers on the Rio Grande. All goods not produced locally in New Mexico had to be hauled from Vera Cruz, Mexico, across 2 000 miles of Indian-infested desert. Only 800 miles of level prairie separated the Missouri River from Santa Fe. But Spanish authorities distrusted the aggressive Yankees and wanted none in New Mexico. A few who tested the possibilities suggested by Pike's narrative wound up in the calabozo adjacent to the ancient Palace of the Governors. Then in 1821 revolution broke out in Mexico. Spain lost her hold on the American colonies. The infant Mexican nation tore down the frontier barriers and welcomed American traders to Santa Fe.

Mountain Branch of the Santa Fe Trail approaching Fort

Union from the north. The fort can he seen in the center, arsenal at

right.

Photo by Laura Gilpin.

In this same year several enterprising Missourians inaugurated the Santa Fe trade. William Becknell lashed trade goods to some mules and headed west. So did Hugh Glenn and Jacob Fowler. Robert Baird and James McKnight, released from prison in Santa Fe, hastened to Missouri and returned with pack trains. In 1822 Becknell cast the mold of the Santa Fe trade by hitching mules to three wagons loaded with merchandise and driving them across the plains to the New Mexican capital. Other merchants saw and took heed. By the closing years of the decade, caravans annually pushed west from the Missouri River destined for a summer of "adventuring to Santa Fee."

In 1825 the Federal Government lent a hand by sending a surveying party under George C. Sibley to mark out a suitable road, But in the end the wagonmasters, following the most direct and easy path, showed the way. The wagon wheels cut deep ruts in the prairie sod. The ruts broadened into a trough, often several hundred feet wide, that still scars long stretches of grassland in Kansas, Oklahoma, and New Mexico. By 1830 the traveler had no difficulty following the great wilderness highway called the Santa Fe Trail.

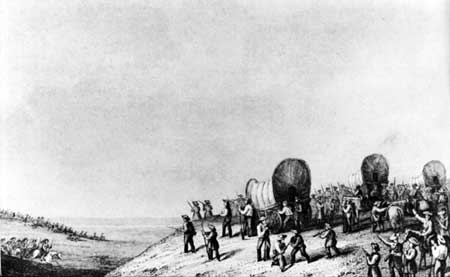

"Indian Alarm on the Cimarron River." Artist

unknown.

Denver Public Library Western Collection.

It began on the west bank of the Missouri River, first at Franklin, later at Independence, still later at Westport. Striking southwest by way of Council Grove, it met the Arkansas River and followed the north bank into western Kansas. At the Cimarron Crossing of the Arkansas River, the trail forked. The shorter and more popular route, the Cimarron Cutoff, turned southwest and headed in a direct line for the New Mexican frontier at the junction of the Mora and Sapello Rivers, near present Watrous. It took the traveler across a parched desert, dreaded because of infrequent waterholes and constant danger of a Kiowa or Comanche war party lurking beyond the next hill. The Mountain Branch offered more water and fewer Indians, but it was almost 100 miles longer and included a rough passage through the Raton Mountains. It followed the Arkansas up to the trading post of Bent's Fort, then turned southwest across the treacherous barrier of Raton Pass, and dropped into New Mexico at the foot of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The two branches reunited in a single stem at the crossing of the Mora and Sapello Rivers, then swung south to thread the mountains at Glorieta Pass, gateway to Santa Fe.

Each spring at Franklin, Independence, or Westport the traders assembled to make ready for the trek to New Mexico. Wagons backed up to warehouses, each to have 5,000 to 7,000 pounds of merchandise packed tightly into its bed. Master products of Pittsburgh and St. Louis wagon builders, these vehicles were especially adapted to plains travel. Built of the lightest, toughest wood obtainable, they were designed for rapid travel over a rough but level terrain. Unlike the famous Conestoga, the floor of its high-sided box had only a slight curve, for on the Plains cargo did not often shift. The iron-tired wheels were universally painted bright red, the bodies light blue. Canvas stretched over arched hickory bows and fastened to the bodies protected the cargo from driving rains. Ten or twelve New Mexican mules or six Missouri oxen drew the heavy wagons. Usually the traders rendezvoused at Council Grove, where they organized into caravans for mutual protection. The drivers mounted the box, cracked their "Missouri pistols" long saplings with a slightly shorter lash ending in a buckskin thong—and the trains crawled west onto the rolling prairie.

"Long-Tom Rifles on the Skirmish Line," by Frederic Remington. The

infantry often saw action, too.

Century Magazine, July

1891.

The 800-mile journey took about 2 months. There was hardship and danger. Rain and hail beat down. Wagon wheels churned the sodden road into a muddy quagmire. Teamsters endured wet clothing and sleepless, fireless nights. Scorching winds whipped across the prairie, and wagons bounced on a rutted trace that damaged cargo and vehicle alike. Clouds of dust hung heavy on the caravans, burning eyes and caking throats. The wheels dried and shrank, and constant repairs were necessary. On the Cimarron Desert the men suffered anxiety over water and Indians. Always thirst tortured them; sometimes, when the springs ran dry, it killed them. Kiowa and Comanche warriors often swept down on a train, exacting a toll in killed and wounded, occasionally capturing a weakly defended train and slaughtering its attendants. In one particularly bad year, 1829, a battalion of United States infantry escorted the caravans to the Cimarron Crossing and turned them over to Mexican troops for the rest of the trip to Santa Fe. Relief came only at the fringes of New Mexican settlement—in the early years San Miguel, later Las Vegas, and in the 1840's the Mora and Sapello Crossings.

"Arrival of the Caravan at Santa Fe." Artist

unknown.

Denver Public Library Western Collection.

On the benchland above Santa Fe the Missourians paused to make themselves presentable for a gala entry. As the caravan worked its way down the narrow dirt streets, the populace stormed noisely from flat-roofed adobe houses to greet los Americanos. Wagons were parked on the plaza in front of the Palace of the Governors, and for a full night the town rang with merriment as traders and townspeople celebrated the occasion. Fandangos, gambling, and liberal quantities of "Taos lightning" and "Paso wine" made men forget the aches of the trail.

Next morning they got down to business. Payment of import duties came first. This was always an exciting contest between merchants trying to reduce the exorbitant Mexican duties and customs officers trying to extort the maximum bribe the traffic would bear. Ordinarily the dispute ended in a friendly compromise, each side winning somewhat less than desired. The traders temporarily rented storerooms and laid out their goods—brightly colored calico and other yard goods, leather goods, hardware of all kinds, crockery, and fancy foods. The customers paid in coin or, as money became scarce, in mules, hides, and furs. Traders tied up their silver coins in green skins that, dried next to a fire, shrank as tightly "as if the metal had been melted and poured into a mold." As the Santa Fe market became increasingly glutted in the 1820's, many of the merchants continued south to towns in Chihuahua and Durango, but this was a long way and required much time. With their profits, the Santa Fe traders were back in Missouri by late autumn. They spent the winter buying another stock of goods, and the following spring once more faced west.

When war broke out in 1846 between the United States and Mexico, the Santa Fe Trail became a military highway. While American armies fought on the lower Rio Grande and in Mexico, Gen. Stephen Watts Kearny led the Army of the West from Fort Leavenworth, on the Missouri River, over the Santa Fe Trail. His objective was the conquest of New Mexico and California. Kearny chose the Mountain Branch, and on the night of August 12 his troops—regular dragoons and Missouri volunteers—camped at the ponds of water just south of where Fort Union later stood. In bloodless triumph the Americans paraded into Santa Fe on August 18 and raised the American flag over the historic plaza at the end of the trail. With part of his army, Kearny rode on to California. In October the occupation force received reinforcements when Col. Sterling Price and another regiment of Missouri volunteers, having followed the Cimarron Cutoff of the Santa Fe Trail, arrived in the New Mexican capital. Throughout the war long strings of freight wagons crawled across the plains to supply the Army in New Mexico.

The Mexican War turned the international highway into a national highway, linking the States with the new Territory of New Mexico. The tariff vanished, and at the same time the market expanded enormously as Americans settled on the Rio Grande and the Army built scattered mud forts to protect the citizens from hostile Indians. Stagecoaches of the Independence-Santa Fe Mail made their way back and forth across the plains, sharing the road with long files of white-topped freight wagons. The merchant-speculators of the 1820's and 1830's gave way to freighters specializing in hauling government and company goods under contract. "Kearny's baggage train started a new era in plains freighting," wrote the historian Frederick Paxson. "It became a matter of business, running smoothly along familiar channels." The volume of business dwarfed the pre-war trade. The value of goods hauled over the trail rose from $15,000 in 1822 to $45,000 in 1843 and to $5,000,000 in 1855. In the single year of 1858, 1,827 wagons crossed the plains to deposit in New Mexico warehouses almost 10,000 tons of merchandise, much of it destined for the Army.

The trail also bore wagons of immigrants from the States. In 1848 James Marshall discovered gold in California. Many gold seekers pointed their teams west on the Santa Fe Trail. Some tired of the journey or lost their enthusiasm and settled in New Mexico. Most went on to the Pacific by way of the Gila Trail or the Cooke Wagon Road, which the Army of the West had opened in 1846 and 1847.

The Santa Fe Trail carried the heaviest traffic of its history during the Civil War years, 1861—65, for New Mexico was the major far-western theater of the war. But these were also the last years of the trail's importance. In 1866 the Kansas Pacific Railroad reached out from the Missouri River. As the rails advanced west, they pushed the eastern terminus of the Santa Fe Trail from railhead to railhead. Part of the Mountain Branch continued in use even after the railroad reached Denver. Then in 1878 the Santa Fe Railroad surmounted Raton Pass. Two years later the first engine steamed into Lamy, station for the New Mexican capital, and the Santa Fe Trail passed out of existence.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |