|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

Chasing Kiowas and Comanches, 1860-61

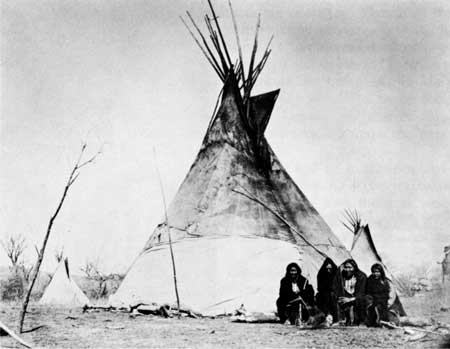

Kiowa tribe. Eonah-pah, or Trailing the Enemy, and wife. Photograph taken by William S. Soule in 1870. Bureau of American Ethnology, The Smithsonian Institution. |

Depredations multiplied in 1860, and from Kansas to New Mexico traffic on the Santa Fe Trail moved under almost constant danger of Kiowa and Comanche attack. In March 1860 Army headquarters in New York ordered three columns to operate independently in the Kiowa-Comanche country during the summer. One was to come from Fort Riley, Kans.; one from Fort Kearny, Nebr.; and a third from New Mexico. Six companies of the Regiment of Mounted Riflemen rendezvoused at Fort Union in May 1860 and rode out in search of the hostiles.

First under Maj. Charles F. Ruff, later under Capt. Andrew Porter, the Fort Union column marched and countermarched in the plains bordering the Canadian River. The elusive Indians stayed out of reach. While the command was on the Pecos River, far to the south, word came that the Comanches were in the north and preparing to attack Fort Union itself. Reinforcements hastened to strengthen the defenders, but no enemy appeared. While the troops scouted the country east of the Canadian, however, Comanches swept down on a temporary supply camp, only to be driven off by the two companies of infantry posted as guard. In July the Mounted Riflemen stumbled on a hostile village, but the occupants had sensed danger and fled. Finally, in October, the department commander suspended further operations.

For 5 months the Fort Union column had pressed an arduous search for the Plains marauders, yet the chief result was a collection of broken-down horses suffering from overwork, malnutrition and the ravages of a disease known as "black tongue." Smarting under the failure, the officers looked forward to another chance. It came in December when Lt. Col. George B. Crittenden commanding Fort Union, learned that a war party of Kiowas and Comanches was harassing traffic on the Mountain Branch of the trail about 70 miles north of the fort.

Comanche tribe. Paro-o-coom, or He Bear's Camp. From a photograph by

William S. Soule, 1867—74.

Bureau of American Ethnology, The Smithsonian Institution.

With 88 men of the Mounted Rifle Regiment he marched up the trail. The Indians, however, had moved east and were menacing the Cimarron Branch. The troops followed the trail night and day and, on January 2, 1861, charged a village of 175 lodges on the Cimarron River 10 miles north of Cold Springs. The Indians were driven from their camp with a loss of 10 killed and an unknown number wounded. Crittenden had three men wounded. The soldiers destroyed the village and its contents and returned to Fort Union with 40 captured horses.

"Early Dawn Attack," by Charles Schreyvogel, typifies

several engagements with the southern tribes.

Library of

Congress.

Colonel Fauntleroy, now department commander, was elated, and in March reported that the Comanches had withdrawn from the borders of the territory. Some of the chiefs, in fact, came to a conference with military authorities on the Pecos River and promised to give no more trouble.

Fauntleroy next turned to the Mescalero Apaches, who had terrorized central and southern New Mexico for many years. He sent Colonel Crittenden south from Fort Union to operate against these Indians. No battles were fought, but Crittenden harried them so relentlessly that by late May Fauntleroy could report that "The Mescaleros have sued for peace, [and] seem disposed to refrain from future hostilities against the settlements."

Actually, neither the Mescaleros nor the Kiowas and Comanches had been pacified, but other matters were absorbing the attention of the Army in New Mexico.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |