|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

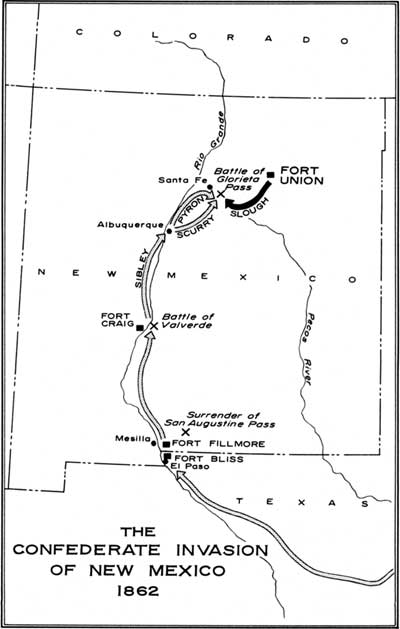

The Confederate Invasion of New Mexico

Sibley's brigade marched north from Fort Bliss in January 1862, aiming for Albuquerque, Santa Fe, Fort Union, and ultimately Denver. At Fort Craig, Canby now had about 3,800 men, largely untested volunteers. The Texans tried to slip around the fort, but Canby sent his men to the east side of the Rio Grande to bar the way. On February 21, 1862, the two armies fought the Battle of Valverde. Although badly outnumbered, the Texans drove the Federals back across the river and into the fortifications of Fort Craig, then pushed north. The quartermaster detachment at Albuquerque burned the military stores and withdrew. On March 5 the garrison at Santa Fe evacuated the capital and fell back on Fort Union. Sibley occupied the two towns. Only Fort Union stood between him and Denver.

Coloradoans had not failed to appreciate their danger. A regiment of volunteers had already been recruited, and late in February marched out of Denver in response to Canby's pleas for help. On March 5, the day Santa Fe was evacuated, components of the regiment rendezvoused on the Arkansas River and struck south on the Santa Fe Trail. Impelled by news of Sibley's victory at Valverde, they embarked on a dramatic forced march to save Fort Union. Covering an average of 40 miles a day, the Coloradoans surmounted snow-choked Raton Pass. On the other side they learned that Albuquerque and Santa Fe had fallen and that Fort Union stood in daily peril. Responding to a plea from their officers, the "Pike's Peakers" pushed on until, after a march of 92 miles in 36 hours, exhaustion finally compelled them to stop for rest. Two more days of marching, in the face of a furious blizzard and dust storm, brought the brigade, at dusk on March 11, to Fort Union.

The commander of the Colorado regiment, Col. John P. Slough, went into conference with the commander of the regulars at Fort Union, Col. Gabriel R. Paul. Slough wished to take the initiative. Paul pointed our that Canby's orders were to hold Fort Union and harass the Confederate advance. Slough argued that only by moving against the enemy could they be harassed. Comparison of the dates on their commissions revealed that Slough ranked Paul. The Coloradoan promptly claimed command of all units at Fort Union and laid plans for advancing to meet the enemy. On March 22 he moved out on the road to Santa Fe with 1,342 men—his own regiment, a battalion of regular infantry, 1 of regular cavalary, and 2 batteries of artillery. Three days later he was at the eastern end of Glorieta Pass.

(click image for an enlargement in a new window)

At this time the Confederate brigade was divided. Part of the 5th Texas occupied Albuquerque. The rest had passed through Santa Fe and, under Maj. Charles L. Pyron, were marching toward Glorieta Pass on the road to Fort Union. At Apache Canyon, west of the pass, Pyron expected to unite with Lt. Col. W. F. Scurry, then camped at Galisteo with the 7th Texas and part of the 4th, all dismounted. General Sibley was in Albuquerque.

Between the Federals and the Confederates lay Glorieta Pass, a rugged defile through the Sangre de Cristo Mountains by which the Santa Fe Trail swung south to avoid the main range of mountains and gain access to the capital city. Here the two armies fought the decisive battle of the Civil War in the Far West.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |