|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

Kit Carson, colonel of the 1st New Mexico Cavalry, 1862—66. Museum of New Mexico |

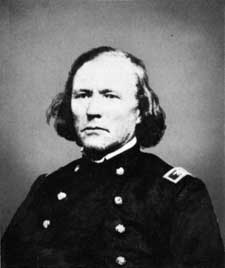

Brig. Gen. James H. Carleton commanded the Department of New Mexico from 1862 to 1866 and prosecuted a relentless war against the hostiles. Museum of New Mexico |

Carleton's Operations, 1862—66

To meet the Confederate threat to New Mexico, Colonel Canby stripped the frontier forts and concentrated his forces on the Rio Grande. In the white man's family quarrel, the Indians of the Southwest saw a chance to pillage ranches and settlements without much danger from pursuing soldiers. By the time General Carleton and the California Volunteers reached New Mexico in 1862, Apaches and Navajos were raiding unchecked through the territory, and Kiowas and Comanches were striking viciously at the Santa Fe Trail and the eastern fringes of New Mexican settlement. Although they had enlisted to save the Union, the Californians joined with the New Mexico volunteers in an attempt to crush the hostiles. For the rest of the war, 1862—65, they campaigned ceaselessly.

General Carleton was a rough, aggressive officer with plenty of frontier experience. He believed in relentless pursuit and harsh punishment. In orders to a subordinate, he summed up his doctrine of Indian fighting: "All Indian men ... are to be killed whenever and wherever you can find them. The women and children will not be harmed, but you will take them prisoners."

Carleton's principal field commander was himself no novice at Indian fighting. Kit Carson, now colonel of the 1st New Mexico Cavalry, was the mailed fist with which the general struck at the hostiles.

Carleton garrisoned the abandoned forts and built new ones. In the winter of 1862—63 he sent Kit Carson to Fort Stanton, in south-central New Mexico, to war on the Mescalero Apaches. By March 1863 Carson had subjugated the tribe and moved 400 warriors with their families to a new reservation on the Pecos River, in eastern New Mexico. Here Carleton built Fort Sumner to stand guard. Carson moved to Fort Union to await further orders.

In June 1863 Carleton turned his attention to the Navajos, for 250 years the scourge of New Mexico. Colonel Sumner tried to conquer them in 1851 and 1852, and failed. Colonel Canby tried again in 1860, also with disappointing results. Now Carleton ordered Kit Carson to march west with the three companies of cavalry at Fort Union and rendezvous with the rest of the 1st New Mexico Regiment for a campaign in the Navajo homeland.

Throughout the summer and autumn of 1863, Carson marched and countermarched in the Navajo country. Not once did he fight, but he captured stock, destroyed crops, and gave the quarry no rest. In January 1864 he invaded the awesome depths of Canon de Chelly, bulwark of the Navajo homeland. It was a shattering psychological blow to the Navajos. Nowhere, they now realized, could they be safe from Kit Carson. Tired, discouraged, and destitute, the bands one by one drifted south to surrender at Forts Canby, Defiance, and Wingate. By the summer of 1864, 8,000 had given up. Carleton had them marched east to Fort Sumner and colonized with the Mescalero Apaches.

The Fort Sumner experiment did not work well. The land would not support so many Indians, who were not especially interested in farming anyway. Moreover, the Apaches and Navajos disliked one another. The Apaches finally broke loose and were not finally subjugated until the late 1870's. For the Navajos, the confinement at Fort Sumner, far from their beloved homeland, was a terrible ordeal. It utterly broke their aggressive spirit. They went home in 1868, resolved never again, no matter what the provocation, to challenge the white man.

On the east the Kiowas and Comanches had grown increasingly troublesome. By 1864 the plains were in the throes of a disastrous war, and caravans on the Santa Fe Trail traveled in constant peril. Carleton took steps to guard his supply line. During the travel seasons of 1864 and 1865, detachments of cavalry rode out of Fort Union to establish camps at strategic points on both the Mountain and Cimarron Branches of the trail. For a time, too, Carleton offered escort service. Trains collected at Fort Union and once a week moved out with cavalry guards. The escort went as far as the Arkansas River, then waited for a west-bound train to accompany back to Fort Union. This service, however, required more troops than could be spared and soon had to be abandoned.

Never one to stay long on the defensive, Carleton decided to strike an the home country of the Indians who were raiding the Santa Fe Trail. In November 1864 he sent Kit Carson and his regiment into the Texas Panhandle, heart of the Kiowa-Comanche country. On November 26 the troops attacked a large camp of Kiowas on the Canadian River near the ruins of a trading post once operated by William Bent. Joined by Comanches, the Kiowas counterattacked and besieged Carson in the ruins. The Battle of Adobe Walls raged all day, but mountain howitzers kept the Indians at bay. At dusk the troops burned the Kiowa village and withdrew.

In the East the long Civil War finally ended at Appomattox Court House in April 1865, and the victorious Union armies dissolved. On the western frontier, the volunteer regiments that had struggled against Indians instead of Confederates one by one went home to be mustered out. Once more the regulars came west to garrison the forts and fight Indians. By autumn of 1866 the California and New Mexico volunteer regiments had been released, and General Carleton had relinquished his command.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |