|

FORT UNION National Monument |

|

The Campaign of 1868

The plains war raged on through 1866 and 1867. Kiowas, Comanches, Cheyennes, and Arapahoes ravaged the settlements of Kansas and eastern Colorado. Military operations focused in Kansas thus drawing the hostiles away from the lower end of the Santa Fe Trail and affording New Mexico relief from the plains warriors. But Fort Union did not remain untouched by the war.

In the autumn of 1868, Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan decided to organize a winter campaign against the plains tribes. He planned to have four columns converge on the winter campgrounds of the hostiles in what is now western Oklahoma. One was to come from New Mexico. Maj. A. W. Evans organized the New Mexico column at Fort Bascom, 130 miles southeast of Fort Union. It consisted of six troops of the 3d Cavalry, three of which were from Fort Union, a company of infantry from Fort Union, and a battery of four howitzers. (Two hundred Utes also joined up to fight their old enemies, but after drawing arms, ammunition, and clothing at Fort Union, changed their minds and with their new treasures went back home.) Evans began his thrust down the Canadian River on November 18, 1868.

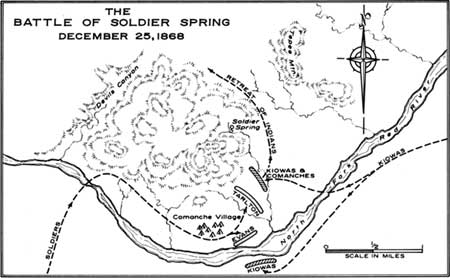

Building a supply depot 185 miles down the Canadian, Evans spent an exhausting month scouring the country to the east. He found abundant sign of Indians but could locate none to attack. Finally, on Christmas Day, he sent Capt. E. W. Tarlton and his troop to pursue two warriors who, from distant hills, had been watching his movements for several days. The chase led into the narrow valley of the North Fork of Red River, on the western flank of the Wichita Mountains. Suddenly the 34 cavalrymen met head on a charging mass of about 100 mounted Comanches. A volley dropped four and turned the charge.

Tarlton sent for help. Joined by two more troops and two howitzers, he pushed down the river. In 2 miles he came upon a village of 60 Comanche lodges belonging to Chief Arrow Point. The tepees covered the left bank of the river on the edge of a grove of timber. Low mountains rolled off to the north. The Indians were working frantically to remove their possessions from the camp, but fled precipitously when a howitzer shell burst in their midst. The cavalry rushed through the village and formed among some rocks atop a ridge on the opposite side. In their front, the warriors took position among rocks on a parallel ridge.

Evans now arrived with the balance of the command. But the Comanches, too, received reinforcements. About 100 warriors from a Kiowa camp located farther downstream joined the fight. Some strengthened the Comanches exchanging fire with Tarlton, while others threatened his right and rear from across the river. Evans extended the line along the river to meet the new threat. He later estimated that about 200 warriors now opposed him. His own force numbered about 300, one-fourth of whom were detailed to hold the horses. While the two sides skirmished, troops were pulled from the line and sent to destroy the village and its contents, including the band's entire winter food supply.

The Indians showed no desire to close in a serious contest and fell back every time the troops advanced. Major Evans knew that he could not sustain a long pursuit with his wornout horses. As night approached, he decided no break off the battle and withdraw.

The infantry company, however, occupied a position from which it could not retire without exposing itself to a destructive fire. Evans therefore ordered Tarlton's three troops of cavalry to drive the enemy from their ridge. As the advance began, the warriors ran down the reverse slope of the ridge and mounted their ponies. Before the Indians could scatter, the cavalry reached the top of the ridge and, from a range of only 150 yards, poured a devastating fire from Spencer repeating carbines into the compact mass of Indians below. On Tarlton's left, Capt. Deane Monahan and his troop caught another parry of warriors at exactly the same disadvantage. In each group about a dozen men were seen to fall, but their comrades carried them from the field. All opposition now dissolved, and the enemy galloped up the canyon leading to Soldier Spring. Evans pulled out that night.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

In the Battle of Soldier Spring, Major Evans estimated that he killed 20 to 25 warriors and wounded an unknown number. His own loss was one man mortally wounded. In the destruction of their food supply, the Comanches suffered a serious blow. Rather than face starvation, most drifted east and surrendered to General Sheridan. Evans was back at Fort Bascom by the end of January 1869, and the Fort Union units returned to their home base.

The Battles of Soldier Spring and the Washita, where on November 27, 1868, Lt. Col. George A. Custer surprised the winter camp of Black Kettle's Cheyennes, broke the resistance of the Plains tribes. They agreed to give up the warpath and settle on reservations.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |