|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

WAIILATPU is the site of the mission founded among the Cayuse Indians in 1836 by Marcus and Narcissa Whitman. After 11 years of ministering to the Indians and assisting emigrants on the Oregon Trail, these missionaries were killed and their mission destroyed by the Indians whom they sought to help. The Whitmans' story of devotion, nobility, and courage places them high among the pioneers who settled the Far West.

In 1836 five people—Dr. Marcus and Narcissa Whitman, the Reverend Henry and Eliza Spalding, and William H. Gray—successfully crossed the North American continent from New York State to the largely unknown land called Oregon. At Waiilatpu and Lapwai, among the Cayuse and Nez Percé Indians, they founded the first two missions on the Columbia Plateau. The trail they followed, established by Indians and fur traders, was later to be called the Oregon Trail.

Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding were the first white women to cross the continent; the Whitmans' baby, Alice Clarissa, was the first child born of United States citizens in the Pacific Northwest. These two events inspired many families to follow, for they proved that homes could be successfully established in Oregon, a land not yet belonging to the United States.

In the winter of 1842—43, Dr. Whitman rode across the Rocky Mountains in a desperate journey to the East to save the missions from closure. On his return to Oregon, another chapter in the western expansion of this Nation was added when he successfully encouraged and helped to guide the first great wagon train of emigrants to the Columbia River. The Whitmans' mission throughout its existence was a haven for the overland traveler. Medical care, rest, and supplies were available to all who came that way.

For 11 years, the Whitmans worked among the Cayuse Indians, bringing them the principles of Christianity, teaching them the rudiments of agriculture and letters, and treating their diseases. Then, in a time of troubles when two opposing forces failed to understand each other, the mission effort ended in violence. In the tragic conclusion, the lives of the Whitmans were an example of selflessness, perseverance, and dedication to a cause. Their story is symbolic of the great effort made by Protestant and Catholic missionaries to Christianize and civilize the Indians in the first half of the 19th century. The missions represented one aspect of American expansion into the vast, unknown lands of the Pacific Northwest.

Call From the West

|

|

No-horns-on-his-head and Rabbit-skin-leggings, both

Nez Percé Indians, were members of the 1831 delegation to St. Louis.

Paintings by George Catlin. SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION |

In 1831 two neighboring tribes west of the Rocky Mountains, the Nez Percé and the Flathead, sent a delegation of their tribesmen to St. Louis, Mo., to seek the white man's religion.

Although their understanding of Christianity was slight and confused, they were interested in learning about it. Their own religion was associated with nature, and they assigned power to natural objects. Their spiritual goal was to attune themselves with nature so that they might acquire power that would make them successful in war or hunting. They sought this white man's religion because, to their minds, it explained the great power possessed by the whites; if they could acquire Christianity, it would increase the power they already had.

In St. Louis the 4-man delegation visited William Clark, superintendent of Indian Affairs, who had passed through their country more than 25 years earlier as one of the co-leaders of the memorable Lewis and Clark Expedition. Myths and legends surround this visit to St. Louis, and the complete story will probably never be known. Yet, it seems probable that they sought the white man's "Book of Heaven" and teachers to show them how to read and write.

Their visit probably would have passed unnoticed had not a man named William Walker become aware of it. While visiting St. Louis in November 1832, he heard from William Clark the story of the Indian visitors. Becoming enthusiastic about helping the Indians of the far Northwest to become Christians, Walker wrote to a New York friend, G. P. Disoway, giving him a rather unusual version of the facts.

He told how Clark had held a weighty theological discussion with the Indians, despite the fact that they could not speak English and no interpreter could be found at the time. He claimed also to have seen the Indians in the city, though two of the delegation had died and the remaining pair had apparently departed 8 months before Walker's arrival. He described them as "small in size, delicately formed, small limbed," and having flat heads. This description hardly fits the stocky, well-built Flathead and Nez Percé, who did not flatten their heads. The famous painter of the West, George Catlin, claimed to have painted portraits of the two survivors of the delegation, and these likenesses indicate the Indians were normally developed. Disoway further flavored the story, and it was printed in New York in the Christian Advocate and Journal, a publication of the Methodist Episcopal Church.

This call from the West was immediately heard by various churches in the United States. Several missionary organizations became active in finding men and women to send to the Pacific Northwest as missionaries. Among them were the Mission Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church; the Roman Catholic Order of the Society of Jesus; and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, then supported by the Presbyterian, Congregational, and Dutch Reformed Churches.

|

|

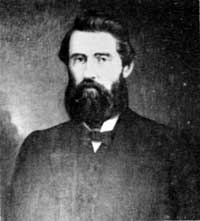

Jason Lee. ANGELUS COLLECTION. UNIVERSITY OF OREGON LIBRARY |

The first to respond was the Methodists' Mission Society. In 1834 Jason Lee and four associates joined the Wyeth Expedition and headed for the Northwest. Lee did not stop in Flathead or Nez Percé country but went on to the lower Columbia and selected a site in the beautiful Willamette Valley. The Methodists established their mission near a small French Canadian farming settlement close to present-day Salem, Oreg. These settlers, who originally were trappers for the Hudson's Bay Company, had turned to farming when the fur trade declined.

Reinforced with 13 new workers in 1836 and 50 additional persons in 1838, the Methodists began missions at The Dalles, the Clatsop Plains, Fort Nisqually, the Falls of the Willamette, and Chemeketa—now Salem.

Their work among the coastal Indians was not very successful. New diseases brought by the whites were fatal to these tribes, and the number of Indians along the Willamette and lower valleys was rapidly declining.

Also, they simply were not interested in the "Book of Heaven." Those who attended services wanted to be paid for coming, for it was not these people who had asked for missionaries. Although Jason Lee was the first missionary, the Nez Percé and the Flatheads were still awaiting a response to their call. The answer was soon to be supplied by another group of missionaries.

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |