|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

The Oregon Country

The tide of European adventurers and explorers had long pressed upon the Pacific Northwest coast. Britain, France, Russia, Spain, and that fledgling nation, the United States, made claims along the rock-strewn shores as they searched for the elusive Northwest Passage between the two oceans and grasped for the wealth offered by the pelts of the sea otter.

Early in the 19th century overland explorers from Britain and the United States began mapping the vast area that stretched from the Rocky Mountains to the Pacific and from the Russian settlements in the north to Spanish California. This was the Oregon Country. Alexander Mackenzie, Simon Fraser, and David Thompson made their way overland for the British crown. In 1804 President Thomas Jefferson sent an expedition led by Meriwether Lewis and William Clark to find a route to the Pacific.

Soon came the fur-trading companies, competing furiously for beaver pelts and thereby exploring much of the Northwest and strengthening national claims. Working its way down the Columbia River, the Canadian-based North West Company dominated the area between 1807 and 1821. John Jacob Astor challenged it briefly when his Pacific Fur Company established Fort Astoria at the mouth of the Columbia. In the American Rockies another company organized by Astor, the American Fur Company, obtained a virtual monopoly in that region by 1835.

But the giant of all the trading firms was the Hudson's Bay Company. Growing steadily larger, it merged with the North West Company in 1821 and thereby inherited the fur wealth of the Oregon Country.

In the early 19th century, many Americans believed that the western boundary of the United States should be the Pacific. They also believed that the northern boundary west of the Rockies should be set at least as far north as the 49th parallel. But Britain was not willing to give up its interests on the lower Columbia. In 1818 the two countries agreed to a temporary arrangement for joint occupation of the whole area. Citizens and subjects of the two nations could enter the Oregon Country without affecting either nation's claims. The United States also reached agreements with Spain and Russia that resulted in these two countries surrendering all claims to the land between California and Alaska.

Despite the joint-occupation agreement, the Hudson's Bay Company was in almost complete control of Oregon after 1821. The United States, however, was able to keep alive its claims through the activities of some of its more colorful citizens. In 1828 the magnificent trail blazer Jedediah Smith visited Fort Vancouver, the Columbia headquarters of the Hudson's Bay Company. A few years later Capt. Benjamin Bonneville explored and trapped the western slopes of the Rockies. In 1832 and 1834 Nathaniel Wyeth attempted unsuccessfully to establish a permanent foothold on the Columbia River.

This was the Oregon Country to which the missionaries came. Other than the scattered Hudson's Bay forts and a handful of settlers near Fort Vancouver, the vast land was empty except for the transient trappers and, of course, the Indians.

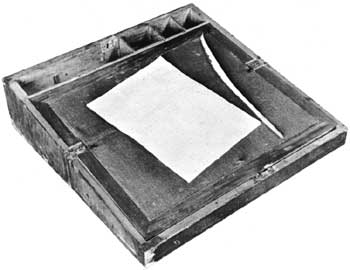

Narcissa Whitman's portable writing desk and quill pen.

OREGON HISTORICAL SOCIETY

Narcissa Whitman's Letters

Mary Walker, who was a prolific writer herself, once recorded in her diary a cutting remark about Narcissa Whitman spending too much time writing letters home. But it is from Mrs. Whitman's detailed and fascinating letters that we get a close view of the lives of the missionaries in Oregon. Highly intelligent and a keen observer, Narcissa Whitman was able to capture the color and drama of her trip west and life among the Indians. Although her letters increasingly recounted moments of melancholy and loneliness, they also disclosed a lively, vivacious woman who was blessed with a fine sense of humor.

Her diary—really a series of letters written while crossing the continent—reveals clearly a lady of charm who was interested in all things and people who came her way. Later, in the Pacific Northwest, when death had taken her only child and it became clear the Cayuse were not interested in Christianity, Mrs. Whitman's letters show her deep worry over her role in the mission field. At times she despaired of her own worth and wished she could give her place to others. It is likely, however, that she did not realize her own intelligence and relatively sophisticated personality were a barrier between her and the Indians. A friend wrote after her death that the Indians considered Mrs. Whitman to be remote and haughty. He added that this was not her fault; it was her misfortune.

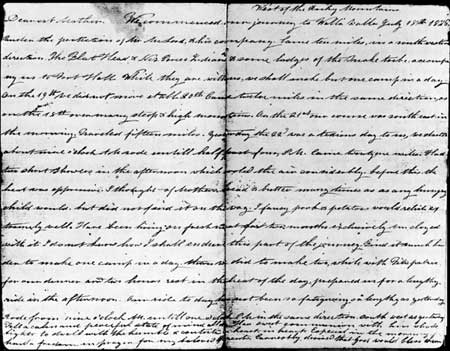

A page from one of Narcissa Whitman's letters written

to her family while crossing the continent. It was this series of long,

de tailed letters that became famous as her diary.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

WHITMAN COLLEGE

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |