|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

Starting a New Life

On the north bank of the Walla Walla River, 22 miles upstream from its junction with the Columbia, Marcus Whitman selected the site of his mission on the lands of the Cayuse Indians. Henry Spalding picked a site 110 miles to the east on Lapwai Creek, 2 miles from its confluence with the Clearwater; the Nez Percé tribe at last had a missionary.

This photograph of the Spalding mission cabin at

Lapwai—now called Spalding—was taken in 1900.

Whitman selected Wai-i-lat-pu, "the place of the rye grass," for several reasons. Close to Fort Walla Walla at the mouth of the river, Waiilatpu was near both a source of supply and the main travel route between Canada and Fort Vancouver. Whitman must have realized, too, that its location was on the line of march between South Pass in the Rockies and the Columbia, the trail that Americans would surely follow. In addition, it was the home of the Cayuse Indians, a "heathen's" tribe that in the minds of the missionaries needed to be saved as much as any.

For his wife's arrival from Fort Vancouver, Whitman built a crude log lean-to as a shelter against the oncoming winter. When Narcissa arrived at Waiilatpu on December 10, she found that the little structure had two bed rooms, a kitchen, a pantry, and a fireplace, but was still without windows and doors. Narcissa, though expecting her first child, accepted her lot in good humor and set out to make a home. Meanwhile, Whitman, Gray, and their helpers worked steadily on the main part of this first house.

Because of the scarcity of suitable timber, the main part of the one-and-a-half story house was made of sun-dried adobe bricks. With great difficulty, enough pine boards were whipsawed in the Blue Mountains 20 miles away to make the floor. The roof was made of poles covered with earth and rye grass. From the cottonwoods that grew along the river, some furniture was made. Pierre Pambrun contributed by sending a small heating stove and a rocking chair from Fort Walla Walla. Bedsteads were boards nailed to walls, and, except for a feather tick Narcissa had acquired at Fort Vancouver, corn husks and blankets served as mattresses.

But even before it was finished, the first house was flooded by the Walla Walla River, just a few feet away. After a second flood, Whitman reluctantly decided that it would be necessary to build again on higher ground. Work was begun on the new T-shaped mission house in 1838. A few years later, the abandoned first house was torn down, and its adobe bricks were used to build a blacksmith shop.

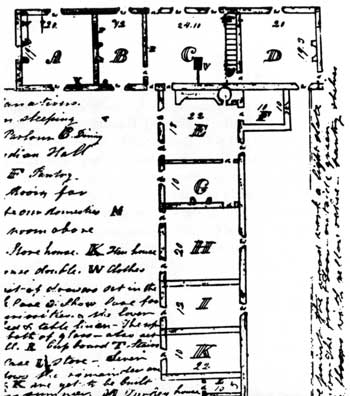

Narcissa sent this floor

plan of the mission house to her mother while the house was still being

built. Room A, which was to be her bedroom, was not constructed.

Instead, room B was used for that purpose.

During the first year, the missionaries depended on the Hudson's Bay Company for provisions to tide them over to their first harvest. From Fort Vancouver, Fort Walla Walla, and Fort Colville (in northeastern Washington), they bought pork, flour, butter, corn, and potatoes. Occasionally the Indians sold them fish and venison.

Horses purchased from the Cayuse provided steaks and stews. As Dr. Whitman put it:

we have killed and eaten twenty-three or four horses since we have been here, not that we suffered which causes us to eat them, but if we had not eaten them, we would have suffered. . . .

In the spring of 1837 the first plantings of vegetables and grains were made. Also in that first year, both Spalding and Whitman planted apple orchards.

At the same time, the missionaries began their efforts among the Indians. Both men encouraged the Cayuse and Nez Percé to start cultivation of the soil. Although the Cayuse had an epidemic of sickness at this time, some of the families did plant crops before departing for the hill valleys to dig camas bulbs in the early summer of 1837. Whitman was greatly encouraged by this hesitant start. He wrote: "When they have plenty of food they will be little disposed to wander." He greatly desired to lead them from their nomadic ways and to have them establish settled communities. But the Indians lacked skills and tools, and the results of their farming were far less than either their enthusiasm or the missionaries' expectations.

Both stations also began educational, spiritual, and medical work. Spalding and Whitman were preachers, teachers, doctors, and farmers; and Narcissa and Eliza assisted them in all these phases of their work.

Since the Nez Percé tongue was understood by both tribes, it was used as the language of instruction at both stations. This meant that only one alphabet had to be devised and that the same written material could be used at both missions. Henry and Eliza Spalding made the most progress in mastering the difficult Indian tongue, and they took the lead in forming the alphabet and translating material. However, by the autumn of 1837 Marcus and Narcissa had learned enough Nez Percé to begin their school.

Religious instruction was commenced promptly at both Waiilatpu and Lapwai. The Spaldings held daily prayers and conducted worship on Sundays. Handicapped by their slowness at learning the language, the Whitmans resorted mainly to encouraging the Indians to continue their daily prayer meetings, which some of them, inspired by fur traders, had been attending before the missionaries arrived.

Although Whitman was the trained doctor, Spalding also administered to the sick. At first, the Indians were receptive to white medicine; but it was medicine that was later to become a major issue of contention between the Indians and the missionaries. For the time being, however, an encouraging start had been made. The Nez Percé seemed truly happy to have the Spaldings in their midst, while the Cayuse, though less enthusiastic, accepted the Whitmans at Waiilatpu. What were these people like, whom man and wife had come 3,000 miles to convert and civilize?

Nez Percé

The Nez Percé Indians called themselves the Nimipu, "The People." Lewis and Clark, the first whites to travel through the Nez Percé country, called them by two names, the Chopunnish and the Pierced Nose Indians. But available records indicate that very few, if any, of these Indians pierced their noses. Such a custom was common with the Pacific Coast tribes who decorated their noses with sea shells.

Within a few years after Lewis and Clark traveled through present-day Idaho, some unknown person, probably a French-Canadian trapper, changed Pierced Nose to Nez Percé and so the name has come down to us today. The accent over the final "e" is no longer pronounced; Nez is pronounced as it looks, Percé is pronounced "purse." Though some writers no longer use the accent, its usage is considered to be correct by most.

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |