|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

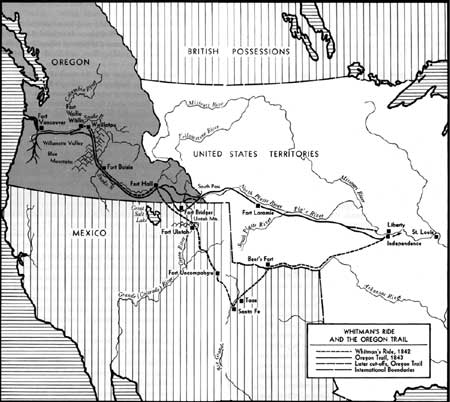

The Ride East

In September 1842 an alarming letter from the American Board arrived at Waiilatpu. It ordered the closing of Waiilatpu and Lapwai and directed Whitman to move to Tshimakain. Spalding, Gray, and Smith were told to return home.

These drastic orders were the result of letters written by Smith, Gray, Rogers, and others, telling the Board of the many dissensions among the missionaries. Reports were sent to Boston about Spalding's bitterness toward the Whitmans, about the feud between Spalding and Gray, and about Smith's constant fault-finding. They told, too, of the inability of the missionaries to agree on policies toward the Indians and toward the independent Protestant missionaries who strayed into the Northwest. The letters recounted in painful detail the petty squabbles that had risen from time to time among all the missionaries.

But before the orders reached Oregon, many of these problems had already been solved. The missionaries, realizing the harm coming from dissension, had agreed to patch up their differences and had had some success in doing so. The Smiths had long since left the mission, and the Grays were about to go. Meeting at Waiilatpu to discuss the orders, the missionaries first decided not to put the directive into effect until the Board should hear of the improvements that had been made. This would take time, for it was not unusual to wait a year or more for an answer to a letter. Deeply concerned over the matter, Whitman made the sudden decision that he should go at once to Boston to talk to the Board's Prudential Committee. Reluctantly, the other missionaries agreed.

On October 3 Whitman set out on his remarkable ride across the continent in the height of winter. Accompanied by a newly arrived emigrant, Asa Lovejoy, and an Indian guide, Whitman reached Fort Hall on the upper Snake River after 15 days of travel. Persuaded to detour to the south because of rumors of Indian wars east of the Rockies, the tiny party crossed the Uintah Mountains to Fort Uintah, in Utah. The hazardous trip was made through deep snow and in bitter cold.

Following the Uintah, Colorado, and Gunnison Rivers, Whitman reached Fort Uncompahgre, Colo. From there, he set out for Taos in northern New Mexico, but had to return when his guide became lost. Severe winter storms continued to harass Whitman and Lovejoy, but by mid-December they reached Taos. On the trail to Bent's Old Fort on the Arkansas River, they learned that a group of mountain men were leaving the fort for St. Louis. Whitman pushed on ahead to catch this party before it left.

Later when Lovejoy reached the fort, he discovered that Whitman had not yet arrived. Sending word to the mountain men to wait, Lovejoy turned back and found Whitman, who in his haste had become lost. Exhausted, Lovejoy stayed at Bent's Old Fort until summer, when he joined Whitman at Fort Laramie for the return trip to Oregon. On February 15 Whitman reached Westport, Mo. By March 9 he was in St. Louis, and about March 23 he arrived in Washington, D.C.

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Even after he reached Boston, Whitman left no written record of his overland journey. Although Lovejoy did write about it in later years, his account includes only the western part of the trip. For the last half of the journey, we must rely on the accounts of those who saw Whitman as he traveled toward the American Board headquarters at Boston. On reaching civilization at St. Louis, it is probable that he gave up the saddle gladly and traveled to Washington by steamer and stagecoach.

In Washington, Whitman visited Secretary of the Treasury J. C. Spencer, an old friend. It is possible, too, that he was introduced to President John Tyler. This stopover in Washington caused many people years later to claim that Dr. Whitman had ridden East to persuade the government to save Oregon from the British, an argument not widely accepted today. Most historians agree that Whitman's ride was to save the missions and that the trip through Washington was secondary.

The great weakness in the "save Oregon's" theory was that it failed to distinguish between the reasons for the trip and the results that came of it. This theory also tended to link the causes of the journey with the results of all Whitman's later efforts in Oregon, including assistance to the American emigrants and the development of Waiilatpu as an important way station on the Oregon Trail.

When Marcus Whitman arrived at New York City about March 25, he was interviewed by Horace Greely, the famed editor of the Tribune. At New York the doctor boarded the Narragansett and sailed to Boston, where he arrived March 30. Despite the rough seas of the Atlantic coast, this part of the extraordinary trip must have seemed calm to Whitman after the hundreds of miles on horseback through the winter snows of the Rocky Mountains and the western prairie—a journey of hardships rarely paralleled in American history.

In the office of the American Board Whitman was greeted with coldness, but the Board agreed to listen to his reports and arguments in favor of the Oregon field. In all respects, Whitman's visit was a successful one. The Board rescinded the unfavorable orders and agreed to send reinforcements to Oregon if suitable persons could be found.

His task accomplished and a hasty visit paid to his home, Whitman began his return trip to Oregon in April 1843. At Independence, Mo., he joined that years migration of almost 1,000 people who were preparing to follow the Oregon Trail.

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |