|

WHITMAN MISSION National Historic Site |

|

The Massacre

When Monday, November 29, 1847, dawned cold and foggy in the Walla Walla Valley, there were 74 people staying at the Waiilatpu mission. Most of them were emigrants, stopping over on the way to the Willamette Valley. The mission buildings were crowded almost beyond capacity: 23 people were living in the mission house; 8 in the blacksmith shop; 29 in the emigrant house; 12 in the cabin at the sawmill, 20 miles up Mill Creek; and the 2 half-breeds, Lewis and Finley, were living in lodges on the mission grounds.

The Whitmans, aware that a crisis was at hand, had discussed what they should do. Both Marcus and Narcissa rejected the idea of attempting flight. Dr. Whitman believed that if the Cayuse went on the rampage only he would be involved and the others would not suffer on his behalf. Courageously, the missionaries decided to continue administering to the sick and to attempt to keep peace with the Indians. On that Monday morning, Marcus treated the ill and officiated at the funeral of an Indian child. Narcissa, ill and temporarily despondent, remained in her room until nearly noon, not touching the breakfast brought to her.

After lunch Whitman stayed in the living room, resting and reading. Narcissa, feeling better, was in the room also, bathing one of the Sager girls. Throughout the rest of the mission, the duties of the day were being carried out. Several children were in the classroom where L. W. Saunders had begun to teach that day after a forced vacation caused by the measles epidemic. Isaac Gilliland, a tailor, was working in the emigrant house on a suit of clothes for Dr. Whitman. At the end of the east wing of the mission house, Peter Hall was busy laying a floor in a new addition being built that autumn. Out in the yard, Walter Marsh was running the gristmill, and four men were busy dressing a beef. There were more Indians than usual gathered about the grounds that day, but it was thought they had been attracted by the butchering.

Into this scene walked two Cayuse chiefs, Tiloukaikt and Tomahas. They entered the mission house kitchen and knocked on the bolted door that led to the living room, claiming they wanted medicine. Dr. Whitman refused them entry but got some medicine from the closet under the stairway. Warning Mrs. Whitman to lock the door behind him, he went out into the kitchen. There, Tiloukaikt deliberately provoked the doctor into an argument. While the doctor's attention was thus diverted, Tomahas suddenly attacked him from behind with a tomahawk. Whitman struggled to save himself but soon collapsed from the blows.

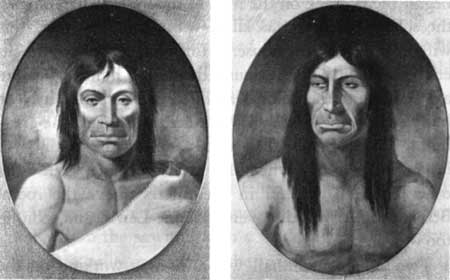

Tiloukaikt and Tomahas, Cayuse chiefs who led the massacre.

Paintings by Paul Kane.

ROYAL ONTARIO MUSEUM. CANADA

Mary Ann Bridger, in the kitchen at this moment, dashed out the north door, ran around the building to the west entrance of the living room, and cried out in terror, "They have killed father!" John Sager, the oldest of the seven orphans, was also in the kitchen when the two Indians fell upon the doctor. John, recovering from the measles, had been busy preparing twine for new brooms. When the doctor was attacked, John attempted to reach for a pistol but was assaulted by the Indians before he could get it. He fell to the floor mortally wounded. At this time, a shot rang out that was apparently the signal for an attack by the Indians in the yard.

At the sound of the shot, the Indians dropped their blankets, which had concealed guns and tomahawks, and began their attack on the men at the mission. Saunders, the school teacher, was killed while trying to reach his wife in the emigrant house. Hoffman, one of the butchers, was killed while furiously defending himself with an ax. Gilliland, the tailor, was killed in the room where he had been sewing. Marsh was killed working at the grist mill. Francis Sager, the second oldest of the family, was in the schoolroom when the attack began. With the other children, he hid in the rafters above the room. Before long he was discovered by Joe Lewis, and soon he too was shot and killed.

Two others—Kimball who also was working on the beef, and Andrew Rodgers who was down by the river—were wounded; but both were able to reach the mission house where Narcissa let them into the living room. A few minutes later, Mrs. Whitman, looking though the window in the east door, saw Joe Lewis in the yard. She called out to him asking if all this was his doing. Lewis made no reply, but an Indian standing on the schoolroom steps heard her voice and, raising his rifle, fired. The bullet hit Mrs. Whitman in the left breast. She fell to the floor screaming but quickly recovered her composure and staggered to her feet.

Narcissa gathered those about her, including several children and the two wounded men, and led them up stairs just as the Indians burst into the living room. In the attic bedroom, a broken, discarded musket was found, and the refugees used it to fend off the Indians. Finally, Tamsucky, an old Indian whom the Whitmans had long trusted, convinced Narcissa that the mission house was about to be burned and that all must go to the emigrant house for safety.

Narcissa and Rodgers agreed to come downstairs, but for the time being the children and the wounded Kimball were to stay. At the foot of the stairs Narcissa caught a glimpse of her husband who now lay dead, his face horribly mutilated. Shocked and weak from loss of blood, she lay down upon a settee. Rodgers and Joe Lewis picked up the settee and carried Mrs. Whitman outdoors. Just beyond the north door of the kitchen, Lewis suddenly dropped his end of the settee, and a number of Indians standing there began firing at Narcissa and Rodgers. After her body had rolled off the couch into the mud, one Indian grabbed her hair, lifted her head, and struck her face with his riding whip. Mrs. Whitman probably died quickly, but Rodgers lingered on into the night.

Kimball remained upstairs with the children through the long night. In the early dawn of Tuesday, he slipped down to the river to get water for them. But he was discovered by the Indians and killed. On that same day, unaware of what had happened, James Young drove down from the sawmill with a load of lumber. He was caught a mile or to from the mission and slain on the spot. A few days later two more victims were added when the Indians killed Crocket Bewley and Amos Sales, two sick youths who dared to openly criticize the Cayuse for the massacre. These two young men brought the death total to 13.

Peter Hall, the carpenter working on the house, managed to escape when the Indians attacked. He made his way to Fort Walla Walla where he received help from the trader, William McBean. Departing from there, he started across the Columbia River to make his way down the north bank to Fort Vancouver. But he never arrived. Perhaps he drowned in the Columbia, perhaps he was caught and killed. Nothing further is known about him.

A few of the people at the mission made successful escapes. W. D. Canfield, one of those dressing the beef, managed to hide in the blacksmith shop until nightfall. Then he set out on foot for Lapwai, 110 miles away. Though he had only a general knowledge of the trail and the direction, he reached Spalding's mission on Saturday. But the most desperate escape was that of the Osborn family. Josiah Osborn, his wife, and their three children were living in the "Indian Room" of the mission house. When the attack came, Osburn hid himself and his family under some loose boards in the floor and escaped detection throughout the afternoon and evening. Crouched under the floor, they could hear the groans of the dying and the sounds of looting above their heads.

After the coming of darkness when the rooms above them grew quiet, the Osborns came out of hiding and made their way silently to the river. They started walking to Fort Walla Walla, but after a short distance, Mrs. Osborn, who had just recovered from measles and the loss of a child at its birth, could not go on. Hiding his wife and two of the children in the willows, Osborn continued on to the fort where he eventually was able to get a horse and a friendly Indian to help him. After some difficulty, he found his family where he had left them and took his wife and children on to Fort Walla Walla. The Osborns did not reach the security of the fort until Thursday—after 4 days in the damp cold of an Oregon autumn. Sick and afraid, all five of the family survived ordeal and eventually reached the Willamette Valley.

At Waiilatpu, the Cayuse were exultant. They had destroyed what they believed had been the cause of all their troubles; once again their lands would be free from the tracks of wagon wheels and the unfathomable ideas of the whites.

Their victory was to be but a short respite. Before long, the Cayuse were to suffer heavily for these deeds. They could not foresee that Marcus and Narcissa Whitman would be regarded as martyrs by their countrymen. They did not understand that Americans could and would wreak a terrible vengeance.

|

|

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |