|

FORT DAVIS National Historic Site |

|

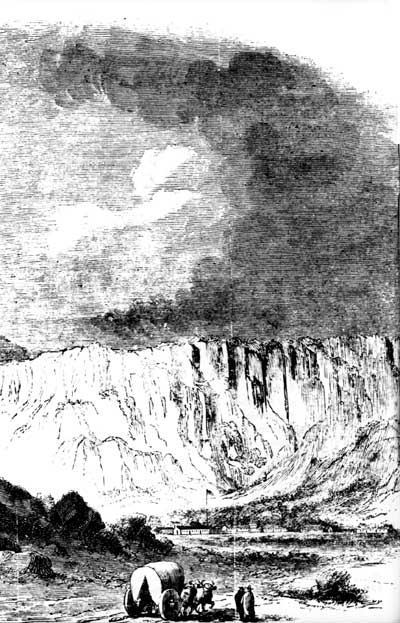

"A Government Draughtsman" sketched the

first Fort Davis for Harper's Weekly, March 16, 1861.

NESTLED AT THE EASTERN base of the scenic Davis Mountains in West Texas, Fort Davis guarded the Trans-Pecos segment of the southern route to California. From 1854 to 1891, except for the Civil War years, units of the United States Army garrisoned this remote post beyond the frontiers of Texas. They patroled the San Antonio-El Paso road, escorted stagecoaches and guarded mail relay stations, policed the Mexican border, and skirmished with Comanche and Apache warriors whose raiding trails to Mexico sliced across the deserts of West Texas. Troops stationed here played a major role in the campaigns against the able Apache chieftain Victorio, whose death in 1880 terminated Indian warfare in Texas. Today the remains of Fort Davis commemorate a significance phase of the advance of the frontier across the American continent.

Blazing Trails in West Texas, 1849

In 1849 West Texas was a vast stretch of wilderness that few Americans had seen. On the west, a scattering of Mexicans lived at points along the Chihuahua Trail, which led down the Rio Grande from Santa Fe through the Mexican city of El Paso del Norte to Chihuahua. Six hundred miles to the east, Austin, Fredericksburg, and San Antonio traced the frontier of settlement in Texas. Between lay a barren, rocky desert broken in the west by a series of rugged desert mountains. Aside from the Pecos and the Rio Grande, a handful of springs and one or two permanent streams furnished the only water. One oasis relieved this hostile country. North of the Big Bend of the Rio Grande, the desert gave way to the Davis Mountains—a jumble of conical peaks and palisaded canyons covered with thick grama grass, dotted with oak trees, and drained by several clear mountain streams.

Few Indians actually lived in this country. Several bands of Mescalero Apaches had villages in the Davis Mountains and the Big Bend, and farther east Lipans menaced the Texas frontier from haunts on both sides of the Rio Grande in the neighborhood of Eagle Pass and Laredo. But many other Indians regularly passed through the Trans-Pecos. Mescalero Apaches from the Sierra Blanca and Guadalupe Mountains of New Mexico and Kiowas and Comanches from the buffalo plains to the north had developed the custom of raiding the haciendas and isolated hamlets of northern Mexico. The Apaches usually swept across the deserts west of the Davis Mountains and crossed the Rio Grande anywhere between the Mexican towns of Presidio del Norte, now Ojinaga, and El Paso del Norte, now Juarez. The Kiowas and Comanches passed east of the mountains and forded at crossings within the present Big Bend National Park. Their raiding parties wore a broad and distinct path, the Great Comanche War Trail, in the prairies and deserts between Red River and the Rio Grande. For Apaches, Kiowas, and Comanches, raiding in Mexico had become an established institution, important to their way of life as a source of food and stock and as a means of winning rank and status in the tribe.

Before the war of 1846—47 between the United States and Mexico, Texans displayed little interest in the country west of the Pecos. The productive land lay east of the 100th meridian, and Comanche war parties stifled curiosity about what lay beyond. The Mexican War changed this. For 20 years Texans had talked of stealing the lucrative "commerce of the prairies" that flowed between Missouri and Chihuahua over the Santa Fe and Chihuahua Trails. A direct road from San Antonio to Chihuahua would considerably shorten the established route and, they hoped, divert the trade through Texas. Now part of the United States, at peace for the first time with Mexico, and possessing a solid claim south and southwest to the Rio Grande, Texans believed that they could at last succeed. In 1848 an expedition of Texas Rangers under Col. John C. Hays and Capt. Samuel Highsmith attempted to open such a road, but the waterless mountains of the Big Bend forced the rangers to return to San Antonio 3-1/2 months later, exhausted and destitute.

Soon the Federal Government discovered a common interest with Texas in opening the Trans-Pecos. As a result of the Mexican War, the United States had acquired not only Texas but the vast territory comprising the present States of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, and California as well. About the time the Hays-Highsmith Expedition limped into San Antonio, the news of gold discoveries in California burst on the Nation. Through letters and promotional literature sent to eastern newspapers, Texans proclaimed the virtues of the southern route to California. Texas senators and many Mexican War veterans urged the southern route as the most feasible for the projected transcontinental railroad. The flood of immigrants that descended on the gulf ports of Texas in 1849 furnished ample testimony to the effectiveness of the promotional campaign. Recognizing an obligation to explore the newly acquired territory, to seek out the best railroad route, to protect immigrants from hostile Indians, and—under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which ended the war—to prevent Indians based in the United States from raiding in Mexico, the Federal Government laid plans to open a road from San Antonio to El Paso.

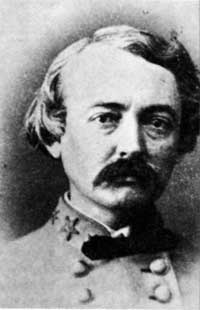

Lt. William H.C. Whiting, Topographical Engineers, commanded the official survey expedition that marked out the San Antonio-El Paso Road in 1849. He is shown here about 12 years later as a brigadeer general in the Confederate Army. National Archives |

Soon after the return of the Hays-Highsmith Expedition, Maj. Gen. William J. Worth, commanding the 8th Military Department (Texas), ordered two engineer officers, Lts. William H. C. Whiting and William F. Smith, to extend the exploration of the Texas Rangers westward to El Paso del Norte. Escorted by nine Texas frontiersmen and guided by Richard A. Howard, the lieutenants left San Antonio on February 12, 1849. By the middle of March they were in the Davis Mountains, where the journey nearly ended. The column found itself suddenly surrounded by about 200 menacing Apache warriors. The grim demeanor of the well-armed Texans inspired the Indians with caution, however, and they ended by escorting the white men to a nearby village for the night. There were five chiefs. Four proved reasonable enough, but Gomez—"the terror of Chihuahua," Whiting called him—was insulting and belligerent. He innocently asked why the Americans did not scatter out and gather wood for cook fires. Patting his rifle stock, Whiting replied that "we held wood enough in our hands." At a council with the chiefs, the lieutenant argued forcefully that the expedition meant no harm and should be allowed to proceed unmolested. While the Americans spent an uneasy night, the chiefs debated. Finally, Gomez was outvoted, and the crisis passed.

On March 20 the little column made its way up a clear stream winding through a deep canyon shadowed by towering basaltic columns. "Wild roses, the only ones I had seen in Texas, here grew luxuriantly," wrote Whiting. "I named the defile 'Wild Rose pass' and the brook the 'Limpia'." Emerging from the pass, the explorers halted beside the creek in a grove of great cottonwoods on the edge of an open plain. On the trunks of the trees the men discovered rude pictographs painted by passing Comanches. Here at "Painted Comanche Camp," where the Limpia flowed from the mountains and turned north toward Wild Rose Pass, Whiting made camp. Countless immigrant parties were to camp here in the next decade, and here, 5 years later, the Army was to build Fort Davis.

Whiting and Smith succeeded in reaching El Paso del Norte and were back in San Antonio by late spring. While they were absent, another party had been west of the Pecos. Led by Dr. John S. Ford, it was financed by a group of Austin merchants. General Worth lent Federal support by assigning the United States Indian Agent for Texas, Maj. Robert S. Neighbors, to accompany Ford. This group pioneered a trail that ran north of the Davis Mountains, close to the New Mexico boundary, before turning southward toward El Paso. Early in June 1849, Worth's successor, Bvt. Brig. Gen. William S. Harney, sent out topographical parties to make additional surveys of the two roads and to improve them for use by wagons. Lt. Francis T. Bryan performed this mission for the northern route, Bvt. Lt. Col. Joseph E. Johnston for the southern. The latter attached himself to a battalion of the 3d Infantry under Bvt. Maj. Jefferson Van Horne, ordered to take station across the river from El Paso del Norte. There Van Horne established the post that was later named Fort Bliss.

|

|

Last Modified: Fri, Oct 18 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |