|

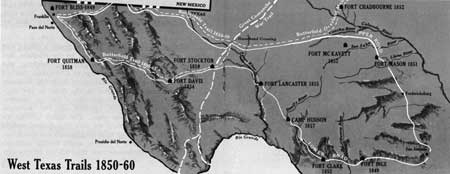

FORT DAVIS National Historic Site |

|

(click on image for an enlargement in a new window)

Field Operations, 1867-79

WHEN THE TROOPS RETURNED TO Fort Davis in 1867, they found the Indians marauding unchecked through West Texas and northern Mexico. Raiding parties of 10 to 15 Mescalero Apaches struck southward from their homes in the Guadalupe and Sacramento Mountains of New Mexico. Although the Davis Mountains Mescaleros seem to have moved elsewhere, other bands lived in the Big Bend of the Rio Grande, a rugged wilderness that few white men had penetrated. They committed depredations on the settlements around Presidio del Norte and in northern Mexico. After a raid they found safety from pursuit simply by crossing the Rio Grande, which was the international boundary. Kiowas and Comanches, too, still found their way south from Indian Territory to prey on the El Paso road and the Mexican villages beyond the Rio Grande.

The first responsibility of Fort Davis was to protect the El Paso road. With the Civil War ended, the flow of traffic resumed its prewar level. Ben Ficklin provided scheduled stagecoach and mail service between San Antonio and El Paso. Units from Fort Davis regularly patroled the road and at times furnished escorts for trains and coaches between Forts Stockton, Davis, and Quitman. Detachments guarded the mail stations at Barilla Springs, El Muerto, Van Horn's Wells, and Eagle Springs.

Frederick Remington's portrayal of a charge by 9th

Cavalry troopers illustrates several actions in which the Fort Davis

soldiers engaged, notably Lt. Patrick Cusack's attack on Apaches in

the Santiago Mountains in 1868

Century Magazine, October 1891

Apache war parties often ran off stock belonging to the Army or to the stage company. A detachment usually went in pursuit, sometimes recovered the stolen animals, and occasionally killed one or two of the thieves. An unusually successful pursuit occurred in September 1868. About 200 Indians raided a train near Fort Stockton and headed south toward Mexico with the stock. Colonel Merritt sent Lt. Patrick Cusack and 60 men of the 9th Cavalry, together with 10 civilian volunteers, to chase the Indians. In the Santiago Mountains of the Big Bend, Cusack overhauled his quarry and attacked. Although badly outnumbered, the soldiers won a decisive victory. The Apaches lost 25 killed and as many more wounded, 200 head of stock, and all their camp equipage. Cusack recovered two Mexican children, captives of the Apaches, and returned to Fort Davis.

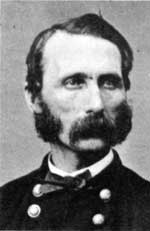

Col. Edward Hatch, 9th Cavalry, dispatched three expeditions against the Apaches in the Guadalupe Mountains during the year he commanded Fort Davis, 1869—70. National Archives |

Colonel Hatch, who relieved Merritt in 1869, believed in offensive action: seeking out the enemy in his home country. During the single year of 1870, he mounted three separate expeditions against the Mescaleros hidden in the Guadalupe Mountains. Only once did his troops succeed in closing in a serious contest. On January 20, Capt. F. S. Dodge surprised a rancheria, killed about 25 Apaches, and captured their stock and camp. The other expeditions involved no battles, but they demonstrated to the Indians that these mountains were no longer a sanctuary.

Colonel Shafter, who followed Hatch, made the same demonstration in another portion of country hitherto regarded as a sanctuary. In the summer of 1871 he turned a routine pursuit of raiders into a remarkable exploration of the virtually unknown southern reaches of the Staked Plains. On June 17 a party of 15 Comanches stole 41 army mules and 3 horses at Barilla Springs. Shafter mounted 63 troopers of the 9th Cavalry and took the trail to the north. For 2 weeks, following first one trail and then another, he marched back and forth in the vast emptiness near the southeastern corner of New Mexico. He penetrated the rolling dunes of the Monahans Sands, which travelers had always avoided. The horses grew weak and gaunt from the wearing service, but the colonel refused to give up. On one very long day the command marched 70 miles without water. Once a village of about 200 Indians was discovered, but the inhabitants scattered before the tired horses could carry their riders within attacking distance.

His horses on the verge of collapse, Shafter reluctantly turned back to Fort Davis, arriving on July 9 after 22 days in the field. He had killed no Indians but had done important service. For the first time since the Civil War, a military column had penetrated the heart of the Staked Plains. Shafter had shown the Army that troops could campaign there and had brought back the geographical knowledge necessary for future operations. And, perhaps more importantly, he had shown the Indians that no longer could the Staked Plains be counted upon to afford refuge from pursuing bluecoats. Three years later, the Army put five columns into this country. In the Red River War of 1874—75 the Kiowas and Comanches were crushed for all time. Fort Davis troops did not participate, but no more would they have to chase the Plains raiders from the north.

Shafter believed that extensive scouting, even though no engagements were fought, produced valuable results. "My experience has been that Indians will not stay where they consider themselves liable to attacks," he informed his superiors, "and I believe the best way to rid the country of them . . . is to thoroughly scour the country with cavalry." In October 1871 he led two troops of the 9th Cavalry and a company of the 25th Infantry out of Fort Davis to apply the technique to the Big Bend. Like the Staked Plains, the area of the present Big Bend National Park had not been "thoroughly scoured" by military expeditions. Again Shafter killed no Indians. But he found abundant evidence of their presence in the Big Bend and added considerably to knowledge of the country.

Col. George L. Andrews, 25th Infantry, commanded the post for 4 years during the 1870's.> National Archives |

The extensive military activity in the haunts of the Mescalero Apaches of New Mexico had its effect. The principal bands turned up at Fort Stanton, N. Mex., in September 1871 and agreed to settle there in peace. For about 4 years, West Texas enjoyed a security previously unknown. Occasional thefts were committed by the Mescalero bands ranging the border country, and a few warriors from New Mexico may have dropped into Texas for similar diversion. But the troops at Fort Davis, commanded for most of this period by Colonel Andrews, enjoyed a respite from Indian duty interrupted only rarely.

One of the most colorful officers to command Fort Davis (1879-80, 1880-810) was Maj. Napoleon Bonaparte McLaughlen, who enlisted as a dragoon private in 1850 and during the Civil War rose to the rank of brevet brigadier general. National Archives |

Then, suddenly, the quiet was broken in 1876. Depredations increased. In May and again in July Apaches killed Mexicans within pistol shot of Fort Davis. The story was the same in 1877. Mutilated corpses of travelers were found along the road from Fort Davis to El Paso. By 1878 petty thievery had given way to a state verging on open war. No longer were the Indians content to steal. Now they also killed whenever possible. Time and again troops from Forts Davis and Stockton trailed raiding parties directly to the Fort Stanton reservation, But the agent contended that his Indians were innocent, and the Army had no authority on the reservation.

Col. Benjamin H. Grierson commanded the 10th Cavalry from its organization in 1866 until his retirement in 1890. He played a significant role in the Victorio war of 1880, commanded Fort Davis from 1882 to 1885, then settled near the post after retiring from the Army. Kansas State Historical Society |

In April 1878 the department commander, Brig. Gen. Edward O. C. Ord, took steps to meet the growing menace. He formed West Texas into the District of the Pecos, with headquarters at Fort Concho. To command the district he appointed Col. Benjamin H. Grierson, famed Civil War general who now commanded the 10th Cavalry. Following General Ord's instructions, Grierson blanketed his district with a network of temporary subposts. Troops stationed at these subposts were to control Indian movements by watching the principal waterholes, to protect the mail route and travelers, and to gain knowledge of the country making up the district. Fort Concho staffed two such posts, Forts Stockton and Davis three each. Those maintained by Fort Davis were at Eagle Springs, Seven Springs, and Pine Springs, the last an abandoned Butterfield station at the southern tip of the Guadalupe Mountains.

Three companies of the 25th Infantry and three troops of the 10th Cavalry, Grierson's regiment, garrisoned Fort Davis. The three cavalry captains, Louis H. Carpenter, Charles D. Viele, and Thomas C. Lebo, were unusually aggressive and capable officers with long records of frontier service. Operating mainly from the subposts, their troops earned Fort Davis the highest scouting mileage for 1878 in the Department of Texas, 6,724 miles. They occasionally skirmished with a raiding party but more often simply marched great distances. The knowledge of the country thus gained was to prove extremely useful in the test to come.

|

|

Last Modified: Fri, Oct 18 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |