|

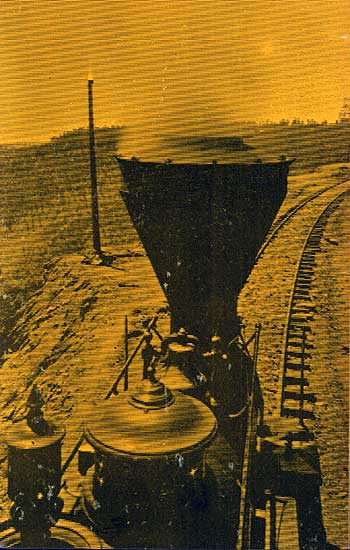

GOLDEN SPIKE National Historic Site |

|

Stanford University

WHEN THE TELEGRAPHER'S THREE DOTS—DONE—flashed coast to coast from Promontory Summit, Utah, at 12:47 p.m., on May 10, 1869, rails from east to west were joined and the Pacific Railroad had become a reality. It had been long in coming.

Despite virtually unanimous public sentiment for a Pacific Railroad, almost four decades of debate and discussion, liberally dosed with meaningless oratory, preceded the driving of the last spike. Within a matter of months after the introduction of the steam locomotive to the United States in 1830, farsighted men conceived the idea of a railroad from the Atlantic to the Pacific. By mid-century, after a rail network had spread over the East and Midwest to the Mississippi River, a railroad to connect this network with the West Coast became a great public issue. Those who advocated the road saw both its necessity and the immediate benefits it would bring to the Nation. But only a few, and they but vaguely, understood the vast influence a Pacific Railroad would have on the continental development of the United States.

ORIGIN OF THE PACIFIC RAILROAD

In 1850 the U.S. House of Representatives' Committee on Roads and Canals succinctly stated the basic motives of the great segment of public opinion that championed the building of a railroad to the Pacific. Such a road, said the committee, would "cement the commercial, social, and political relations of the East and the West," and would be a "highway over which will pass the commerce of Europe and Asia."

Proponents of a Pacific Railroad based their arguments mainly on its commercial importance. The settlement of the Oregon question in 1846, the discovery of gold in California in 1848, and the admission of California to statehood in 1850 swelled the population of the Pacific Coast. And with commerce almost wholly dependent upon the long, slow journey around Cape Horn or across the Isthmus of Panama, both East and West foresaw a large and lucrative trade speeding by rail across the continent. Even more important, the promoters confidently predicted that a Pacific Railroad would divert much of the trade with Europe and Asia from ship to rail. "The real objective point," recalled U.P. executive Sidney Dillon, "continued to be China and Japan and the Asiatic trade."

The commercial motive remained dominant from first to last, but there were other considerations that carried greater influence with Congress, and led the national lawmakers to overcome the deeply rooted opposition to Government-sponsored internal improvement projects and throw the weight of the United States, both moral and material, behind the idea. The railroad would hasten the final subjugation of the American Indians. It would also enormously reduce the time and expense to the United States in transporting mail and Government supplies. With the outbreak of the Civil War, political bonds between California and the Union had to be strengthened to counter the threat of that State's secession. The war also dramatized the defenseless condition of the Pacific Coast. Rapid transcontinental transportation was a necessary ingredient in solving both problems.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |