|

GOLDEN SPIKE National Historic Site |

|

SIGNIFICANCE OF THE PACIFIC RAILROAD

With one exception the Pacific Railroad confirmed the expectations of its advocates and justified the participation of the U.S. Government. Politically, the Railroad Act of 1862 strengthened the loyal element in California, and undoubtedly insured (if insurance were needed) the continued allegiance of the Pacific Coast to the United States during the Civil War. Militarily, the railroad (more accurately, the railroad network that developed between 1869 and 1884) provided the key to conquering the Indians, and the means of considerably improving coastal defenses on the Pacific coast. It also furnished quicker and cheaper transportation for Government supplies and the mail. Commercially, it permitted a vast and profitable trade to develop between East and West. Only in the confident assurance of a huge trade with Asia—the principal motive—were the promoters of the Pacific Railroad disappointed. In November 1869, 6 months after the Golden Spike ceremony, the first ship steamed through the newly completed Suez Canal and destroyed this hope.

Aside from this contemporary significance, there was a larger and more profound significance which the projectors of the Pacific Railroad only dimly perceived. The Union Pacific and Central Pacific hastened the end of the continental frontier. They did not, as writers occasionally generalize, destroy the frontier. "From a narrow strip across the plains," said historian Frederick L. Paxson, "Indians had been pushed to one side and another and a single track had crossed the mountains, but north and south great areas remained untouched, for the demolition of the frontier had only just begun." Nevertheless, "In the history of the frontier the Union Pacific Railway marks the beginning of the end." The end did not come until after completion, in 1882-84, of the other transcontinental railroads, and then as a result of the collective influence of all. But the Central Pacific and Union Pacific established the process by which the end was attained.

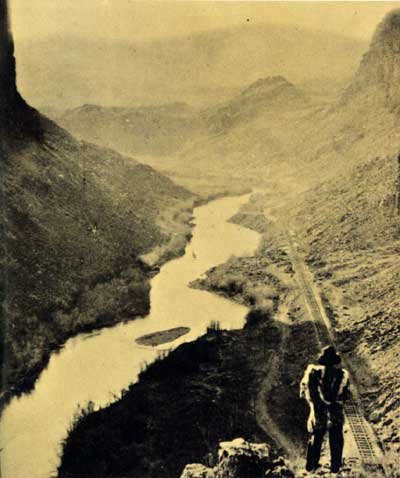

A lone Indian gazes upon C.P. track in the Palisades section of the Humboldt River

Robert Weinstein Collection

This process had two stages. First, the railroad pierced the Indian barrier and gradually ate into it on either side of the right-of-way. Next it brought in its wake immigration, settlement, and development of industry and agriculture. The frontier inevitably disappeared. Settlement of the plains and mountains had been entirely unforeseen by the builders of the first Pacific Railroad, who wished only to bridge the "Great American Desert" and tap the commerce of Asia. But business from along the line came to furnish the bulk of traffic on the transcontinental railroads and tempered the disappointment over failure to capture the Asiatic trade.

Frederick Jackson Turner's famous frontier thesis, advanced in 1893, noted an essential difference between the Midwestern and Far Western frontiers of the United States and the determining role in this difference played by the railroad: "the frontier reached by the Pacific Railroad, surveyed into rectangles, guarded by the United States Army, and recruited by the daily immigrant ship, moved forward at a swifter pace and in a different way than the frontier reached by the birch canoe or the pack horse." Paxson, Turner's leading disciple, carried this thinking a step further: "The effort that finally destroyed the continental frontier differed from all earlier movements in the same direction in that it was self-conscious, deliberate, and national." After 40 years of controversy the principle of Federal aid to internal improvements at last gained general acceptance with passage of the Railroad Act of 1862. With this measure and later amendatory legislation, Congress struck the first really effective blow at the frontier. And while the first transcontinental railroad was under construction, Congress insured the complete collapse of the frontier by legislating aid to the Northern Pacific, Atlantic and Pacific, Texas and Pacific, and Southern Pacific railroads.

Thus the paramount historical significance of the first transcontinental railroad lies in its effect upon the Far Western frontier. It made the first serious and permanent breech in the frontier, and it established the process by which the entire frontier was to be demolished.

A century after the joining of the rails at Promontory Summit, America's transcontinental railroads continue to foster the economic and political unity of the Nation. Sleek diesel liners hasten freight and passengers from Atlantic to Pacific in half the time of their wood-burning ancestors. Speeding across prairie and desert, or threading the passes of the Rockies and Sierra, they symbolize a dream come true beyond the most fanciful imaginings of the promoters and builders of the Pacific Railroad.

Santa Fe Railway

Administration

Golden Spike National Historic Site is administered by the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior. A superintendent whose address is P.O. Box 897, Brighman City, Utah 84302, is in charge.

|

|

Last Modified: Sat, Sep 28 2002 10:00:00 pm PDT |