|

FORT McHENRY National Monument and Historic Shrine |

|

"'Tis the Star-Spangled Banner."

Mural by George Gray.

"The Star-Spangled Banner"

"The Star-Spangled Banner" was written in a time of great national crisis. The Capital of the United States had fallen to the enemy. Its most important Federal buildings were charred ruins in the wake of the British occupation. There seemed to be nothing separating Britain's vaunted military power from complete victory, except the small bodies of scattered and disorganized militia. American morale was at a low ebb. It required a bold man at that time to prophesy the spiritual rebirth of the American Nation as Francis Scott Key did in "The Star-Spangled Banner."

The long chain of fortuitous circumstances which combined to inspire Key to produce his masterpiece began with the British occupation of Upper Marlboro, Md., shortly before the battle of Bladensburg. At Upper Marlboro, General Ross, the commander of the British Army, established temporary headquarters at the home of Dr. William Beanes, a respected and prominent resident, who was required to give an oath of good behavior to the English.

The British remained only a short time at Upper Marlboro. Then they moved on to the battle of Bladensburg and to Washington. After the occupation of Washington the British returned, and once more Dr. Beanes was made acutely aware of their presence. According to family tradition, Dr. Beanes was entertaining some of his friends when the privacy of his home was suddenly intruded upon by three British stragglers. The argument that ensued between the Americans and the soldiers resulted in the arrest of the stragglers and their detention in the local jail on a charge of disturbing the peace. Other accounts, both English and American, state that Dr. Beanes placed himself at the head of a group of Upper Marlboro residents, who pursued English stragglers and captured three for imprisonment in the local jail.

One of the three escaped and reported the incident to the commander of a British scouting party. The latter considered that by this unfriendly act the doctor had violated his pledge to the English. Forthwith, a patrol of soldiers was dispatched to Dr. Beanes' house. They placed him under arrest, then escorted him to the British base on the Patuxent and turned him over to Admiral Cochrane. Thus a chain of events was set in operation which was indirectly responsible for the situation which brought about the composition of the poem, "The Star-Spangled Banner."

Shortly thereafter, news of this incident reached friends of Dr. Beanes. When the initial efforts of residents of Upper Marlboro to secure his release had failed, they called upon Francis Scott Key, a lawyer then living in Georgetown (now a part of Washington), to intercede. Key, who was an intimate acquaintance of the doctor's, agreed to undertake this mission and left for Baltimore carrying letters of introduction officially sanctioning the undertaking.

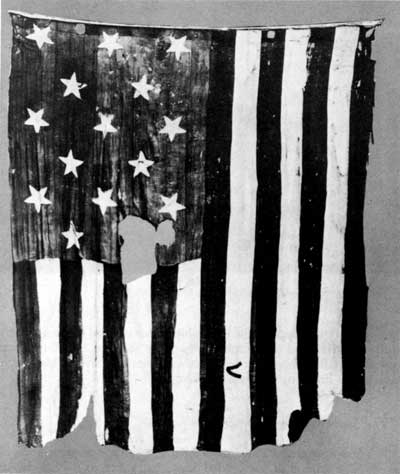

This is the flag which flew over the fort

during the attack and which Francis Scott Key saw by "dawn's early

light." Its original dimensions were 42 x 30 feet. The official flag of

our country from 1795 to 1818 had 15 stars and 15 stripes. The flag is

displayed in the United States National Museum.

Courtesy United States National Museum.

In Baltimore, Francis Scott Key was joined by Col. John Skinner who was a United States Government agent for arranging the transfer of prisoners. On September 5, 1814, the two Americans set sail from Baltimore for the Chesapeake Bay, where they expected to find the English fleet. Two days later they encountered the British on their way to attack Baltimore.

Key and Skinner boarded the Tonnant, flagship of the English Fleet, where they were courteously received by Admiral Cochrane and General Ross and invited to dine in the admiral's cabin. After dinner was served, Key opened negotiations with the British for the release of Dr. Beanes. At first the English were adamant in their resolve to transport Dr. Beanes to Halifax where they intended to punish him for allegedly violating his oath of good behavior.

During these early negotiations the Americans made little progress. Colonel Skinner, however, had carried with him a pouch of letters, written by British soldiers wounded at Bladensburg, extolling the excellent treatment they received at the hands of the Americans. This information tended to mollify the stubborn attitude maintained by the British, and after a brief discussion Admiral Cochrane agreed to release Dr. Beanes.

However, Key and Skinner, who had become aware of the British plans for the attack on Baltimore, were informed that for security reasons they would not be allowed to return to Baltimore until the British objective had been attained. Since the H. M. S. Tonnant was already overcrowded with British military personnel, the two Americans were transferred to the H. M. S. Surprize, a light frigate, where they remained until the fleet reached the mouth of the Patapsco.

The shallow Patapsco compelled Admiral Cochrane, who wished to take personal charge of the vessels assigned to attack the fort, to transfer his flag from the large 80-gun Tonnant to the smaller Surprize. Key and Skinner were then moved back to the small American boat on which they had sailed from Baltimore, and it was from this vessel, anchored somewhere to the rear of the British fleet, that Key witnessed the attack on Fort McHenry throughout the day of September 13 and that night.

John Stafford Smith. Courtesy British Museum. |

Francis Scott Key. Courtesy the Flag House Association. |

For Key, who was a true patriot, this 25-hour vigil was a period of intense emotional stress induced by fear, anxiety, and trepidation for the safety of his country, home State, and loved ones. His feelings are best described in his own words, from a speech he delivered years later at Frederick, Md., before a home-town audience:

I saw the flag of my country waving over a city—the strength and pride of my native State—a city devoted to plunder and desolution by its assailants. I witnessed the preparation for its assaults, and I saw the array of its enemies as they advanced to the attack. I heard the sound of battle; the noise of the conflict fell upon my listening ear, and told me that "the brave and the free" had met the invaders.

In the same speech, he described how his tense emotions were suddenly released at the sight of the American flag still waving defiantly over the ramparts of Fort McHenry at dawn on September 14—the symbol of American triumph which supplied Key with the spark of inspiration:

Through the clouds of the war the stars of that banner still shone in my view, and I saw the discomfited host of its assailants driven back in ignominy to their ships. Then, in that hour of deliverance and joyful triumph, my heart spoke; and "Does not such a country and such defenders of their country deserve a song?" was its question. With it came an inspiration not to be resisted; and even though it had been a hanging matter to make a song, I must have written it. Let the praise, then, if any be due, be given, not to me, who only did what I could not help doing, not to the writer, but to the inspirers of the song!

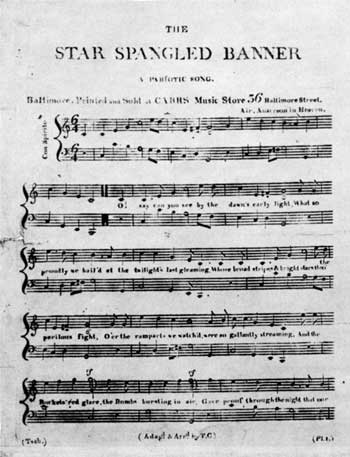

First appearance of "The Star-Spangled Banner" in

print, September 15, 1814.

Courtesy Walters Art

Gallery.

Francis Scott Key started to write the first words of "The Star-Spangled Banner" as the British terminated their attack against Fort McHenry. During his return to Baltimore, September 14, Key added lines to his poem, and that night revised and completed the original draft at the Fountain Inn, in Baltimore (a location now occupied by the Southern Hotel), where he is said to have spent the night.

The next morning, Key showed his verses to Judge Joseph H. Nicholson, of Baltimore, his wife's brother-in-law. The judge was so greatly impressed by the stirring quality of the poem that he either took the manuscript himself or sent it to the printing shop of the Baltimore American. Since the entire staff was absent on military duty at the time, the sole occupant of the shop was a young apprentice named Samuel Sands.

Sands ran Key's poem off in handbill form, and it was distributed to the citizens of Baltimore on September 15 under the title, "Defence of Fort McHenry." The first dated publication of the poem, again under the same title, appeared September 20 in the Baltimore Patriot. Shortly after, the title was changed to "The Star-Spangled Banner." The family papers of Thomas Carr, a music publisher whose shop was at 36 Baltimore Street, state that he was the first to release the words and music of Key's poem under its present-day title in 1814.

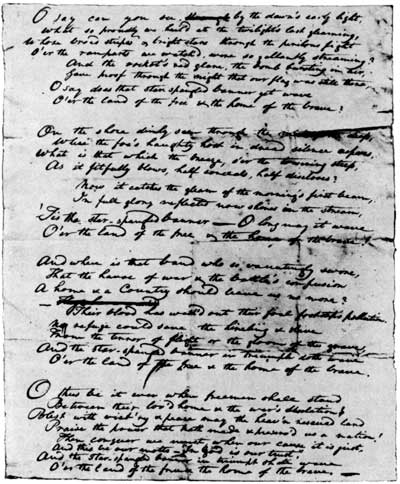

Facsimile of the manuscript draft of "The

Star-Spangled Banner."

Courtesy Walters Art Gallery.

Ferdinand Durang, an actor in Baltimore, may have been the first to sing the words to Key's poem in public. The melody to which the words were adapted is an old English tune originally written by John Stafford Smith, probably very shortly after 1770 and entitled "To Anacreon in Heaven." The occasion which inspired Smith to write this music was the founding in London of the Anacreontic Society.

This melody became popular not only in England but also in Ireland, where, with different words, it served as a drinking song. Later, the melody crossed the Atlantic. One of the earliest adaptations of this old English air in America was the Boston patriotic song by Thomas Paine, "Adams and Liberty," which appeared in 1797. Somewhat later, it was used with other words to the title "Jefferson and Liberty."

Proof of the popularity of this melody in America is the fact that it was adapted to more than 20 different songs. Two songs which were written in 1811 and 1813, respectively, that utilized the melodic theme of "To Anacreon in Heaven" and may have been known to Key, are "The Battle of the Wabash" and "When Death's Gloomy Angel Was Bending His Bow." The former celebrates the American victory at the battle of Tippecanoe, while the latter was written in commemoration of Washington's death for the first anniversary of the Washington Benevolent Society of Pennsylvania. Thus it is entirely conceivable that Francis Scott Key had the bars of the original old English air in mind when he wrote his poem, "The Star-Spangled Banner."

The first printing of "The Star-Spangled Banner" with music.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |