|

MORRISTOWN National Historic Park |

|

Jockey Hollow: the "Hard" Winter of 1779—80 (continued)

GUARDING THE LINES. Keeping the Continental Army intact under all these conditions was but part of Washington's herculean task in 1779—80. Again, as at Morristown in the winter of 1777, and at Middlebrook in the winter of 1778—79, the threat of attack by an enemy superior in man-power and equipment hung constantly over his head. Communications between Philadelphia and the Hudson Highlands had to be protected, and the northern British Army had to be prevented from extending its lines, now confined chiefly to New York and Staten Island, or from obtaining forage and provisions in the countryside beyond.

While the main body of American troops was quartered in Jockey Hollow, certain parts of it, varying in strength from about 200 men to as high as 2,000, were stationed at Princeton, New Brunswick, Perth Amboy, Rahway, Westfield, Springfield, Paramus, and similar outposts in New Jersey. Washington changed the most important of these detachments once a fortnight at first, but toward the spring of 1780 some units remained "on the Lines" for much longer periods. Thus Morristown served again as the vital center of a defensive-offensive web for the northern New Jersey and southern New York areas. The enemy damaged the outer margins of that web on several occasions, notably on June 7 and 23, when they penetrated to Connecticut Farms (now Union) and Springfield, but Washington's defenses were never seriously broken, and through all that winter and spring his position in the Morris County hills remained relatively undisturbed.

THE STATEN ISLAND EXPEDITION. Routine duty on the lines was interrupted on January 14—15 by what might be termed a "commando" raid on Staten Island. This daring expedition, planned by Washington and undertaken by Maj. Gen. William Alexander, Lord Stirling, was prepared with the utmost secrecy. Five hundred sleighs were obtained on pretence of going to the westward for provisions. On the night of the 14th, loaded with cannon and about 3,000 troops, these crossed over on the ice from Elizabethtown Point "with a determination," to quote Q. M. Joseph Lewis, "to remove all Staten Island bagg and Baggage to Morris Town."

Unfortunately for American hopes, the British learned about the scheme in time to retire into their posts, where they could defy attack. After lingering on the island for 24 hours without covering, with the snow 4 feet deep and the weather extremely cold, Stirling's force could bring off only a handful of prisoners and some blankets and stores. What disturbed Washington most, however, was the disgraceful conduct displayed by large numbers of New Jersey civilians who joined the expedition in the guise of militiamen, and who, in spite of Stirling's earnest efforts, looted and plundered the Staten Island farmers indiscriminately. All the stolen property that could be recovered was returned to the British authorities a few days later, but the harm had been done. On the night of January 25, the enemy retaliated by burning the academy at Newark and the courthouse and the meeting house at Elizabethtown. That exploit also marked the beginning of a new series of British raids in Essex and Bergen Counties which kept those districts in considerable uneasiness for several months to come.

SIDELIGHTS ON THE PATTERN OF ARMY LIFE. Except on rare occasions, such as participation in an occasional public celebration might afford, the average soldier found camp life at Morristown hard, unexciting, and often monotonous. Sometimes his whole existence seemed like an endless round of drill, guard duty, and "fatigue" assignments, the latter including such unpleasant chores as burying the "Dead carcases in and about camp." What little recreation the line troops could find was largely unorganized and incidental. Washington proclaimed a holiday from work on St. Patrick's Day 1780, which the Pennsylvania Division observed by sharing a hogshead of rum purchased for that purpose by Col. Francis Johnston, its then commander. Regulations prohibited gambling and drunkenness, however, and the prankster who strayed too far from military discipline "paid the piper" if caught. One soldier, convicted by court martial of "Quitting his Post, and riding Gen. Maxwell's Horse," received 150 lashes on his bare back. This war was a stern business; men who enlisted as privates in the Continental Army were not supposed to be looking for amusement.

The officers were somewhat more fortunate. Most of the generals obtained furloughs and went home to their families for part of the winter. Others could escape the tedium of camp life occasionally at least. Writes Lt. Erkuries Bearry, in a letter dated March 13, 1780: "I got leave of absence for three Days to go see Aunt Mills and Uncle Read who lives about 12 Miles from here . . . that night Cousin Polly and me set off a Slaying with a number more young People and had a pretty Clever Kick-up, the next Day Polly and I went to Uncle Reads who lives about 4 Miles from Aunts, here I found Aunt Read and two great Bouncing female cousins and a house full of smaller ones, here we spent the Day very agreeably Romping with the girls who was exceeding Clever & Sociable." Almost at the same time, "the lovely Maria and her amiable sister" were entertaining Capt. Samuel Shaw, of the 3d Artillery Regiment, at Mount Hope. "By heavens," Shaw confidentially informed a fellow officer on February 29, "the more I know of that charming girl, the better I like her; every visit serves to confirm my attachment, and I feel myself gone past recovery."

Dancing was another popular diversion among the officers that winter. At least two balls were held in Morristown by subscription, one on February 23, and the other on March 3. Lieutenant Bearry mentioned attending "two or three Dances in Morristown," and also "a Couple of Dances at my Brother John's Quarters at Battle [Bottle] Hill." Many of these events were lively affairs patronized by a goodly proportion of the fair sex. Indeed, the energy displayed by "some of the dear creatures in this quarter" nearly exhausted Captain Shaw, who complained that "three nights going till after two o'clock have they made us keep it up."

But for all such pleasurable excursions, the average Continental officer had adversities with which to deal. Frequently, he shared the greatest hardships of his men, and from day to day worked unremittingly to improve their lot along with his own. Nor must it be forgotten that, unlike a private, an officer was expected to support and clothe himself largely from his pay or private means, and that he paid for recreation out of his own pocket. Sometimes officers were so deficient in clothing that they could not appear upon parade, much less enjoy visits with the ladies. Even Washington, at his headquarters in the Ford Mansion, often lacked necessities for his table, or experienced some other inconvenience. "I have been at my prest. quarters since the 1st day of Decr.," he observed to General Greene on January 22, 1780, "and have not a Kitchen to Cook a Dinner in, altho' the Logs have been put together some considerable time by my own Guard; nor is there a place at this moment in which a servant can lodge with the smallest degree of comfort. Eighteen belonging to my family and all Mrs. Fords are crouded together in her Kitchen and scarce one of them able to speak for the colds they have caught."

LUZERNE AND MIRALLES. Among the most interesting events which took place at Morristown in the spring of 1780 were those connected with the Chevalier de la Luzerne, Minister of France, and Don Juan de Miralles, a Spanish grandee who accompanied him, unofficially, on a visit to the American camp. These gentlemen arrived at headquarters on April 19, but Miralles became violently ill immediately afterwards, and it was only Washington's distinguished French guest who could participate in the celebrations that followed during the next few days.

The highlight of Luzerne's visit, which occurred on April 24, was eloquently described by Dr. Thacher: "A field of parade being prepared under the direction of the Baron Steuben, four battalions of our army were presented for review, by the French minister, attended by his Excellency and our general officers. Thirteen cannon, as usual, announced their arrival in the field . . . A large stage was erected in the field, which was crowded by officers, ladies, and gentlemen of distinction from the country, among whom were Governor Livingston, of New Jersey, and his lady. Our troops exhibited a truly military appearance, and performed the manoeuvres and evolutions in a manner, which afforded much satisfaction to our Commander in Chief, and they were honored with the approbation of the French minister, and by all present. . . . In the evening, General Washington and the French minister, attended a ball, provided by our principal officers, at which were present a numerous collection of ladies and gentlemen, of distinguished character. Fireworks were also exhibited by the officers of the artillery." Next day, amid the music of fifes and drums, and with another 13-cannon salute, Luzerne inspected the whole Continental Army encampment. Then he left for Philadelphia, escorted part-way on his journey by an honor guard which Washington provided.

Don Juan de Miralles saw nothing of these parades, entertainments, and reviews. The sickness which had seized him on his arrival at Morristown was to prove fatal. His condition grew steadily worse as the days passed, and on April 28 he died. Final obsequies were held late the following afternoon, and again Dr. Thacher was on hand to describe events: "I accompanied Dr. Schuyler to head quarters, to attend the funeral of M. de Miralles. . . . The top of the coffin was removed, to display the pomp and grandeur with which the body was decorated. It was in a splendid full dress, consisting of a scarlet suit, embroidered with rich gold lace, a three cornered gold laced hat, and a genteel cued wig, white silk stockings, large diamond shoe and knee buckles, a profusion of diamond rings decorated the fingers, and from a superb gold watch set with diamonds, several rich seals were suspended. His Excellency General Washington, with several other general officers, and members of Congress, attended the funeral solemnities, and walked as chief mourners. The other officers of the army, and numerous respectable citizens, formed a splendid procession, extending about one mile. . . . the coffin was borne on the shoulders of four officers of the artillery in full uniform. Minute guns were fired during the procession, which greatly increased the solemnity of the occasion. A Spanish priest performed service at the grave, in the Roman Catholic form. The coffin was enclosed in a box of plank, and all the profusion of pomp and grandeur was deposited in the silent grave, in the common burying ground, near the church at Morristown. A guard is placed at the grave, lest our soldiers should be tempted to dig for hidden treasure. It is understood that the corpse is to be removed to Philadelphia."

THE COMMITTEE AT HEADQUARTERS. The "members of Congress" by Dr. Thacher as having attended Miralles' funeral were undoubtedly Philip Schuyler, John Mathews, and Nathaniel Peabody, who had arrived in Morristown only the day before. These men had been appointed by their colleagues as a "committee at head-quarters" to examine into the state of the Continental Army, and to take such steps, in consultation with the Commander in Chief, as might improve its prospects of winning the war. The committee remained active until November 1, 1780, and during its life rendered valuable service as a liaison body between Congress, on the one hand, and headquarters on the other. Its very first report detailed at length "the almost inextricable difficulties" in which the committee found American military affairs involved. The report also stated, in unmistakeably plain words, what Washington had been saying all along, namely, that Congress itself would have to act quickly if the situation were to be saved.

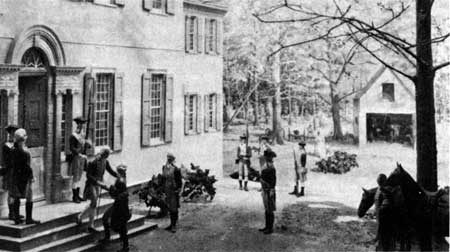

Washington greeting Lafayette on his arrival at headquarters, May

10, 1780.

From a diorama in the historical museum.

LAFAYETTE BRINGS GOOD NEWS. Even as Schuyler and his co-workers penned their report, however, good news was arriving at headquarters. On May 10, 1780, following more than a year's absence in his native France, the Marquis de Lafayette came to Morristown, fortified with word that King Louis XVI had determined to send a second major armament of ships and men to aid the Americans. This assistance would prove more beneficial, it was hoped, than the first French expedition under the Count d'Estaing, which, after failing to take Newport in the late summer of 1778, had finally sailed away to the West Indies. Washington's joy at seeing Lafayette again was doubled by this welcome information, and the army as a whole shared his feelings.

The gallant young Frenchman remained a guest of his "beloved and respected friend and general" until May 14, when he left for Philadelphia, carrying with him letters from Washington and Hamilton informing members of Congress about his work in France. Approximately 6 days later he returned to Morristown, and from that time forth until the end of 1780 he continued with the Continental Army in New Jersey and New York State.

TWO BATTLES END THE 1779—80 ENCAMPMENT. Early in June there was far less cheerful news. Reports reached camp that the enemy had taken Charleston, capturing General Lincoln with his entire army of 5,000 men. Worse still, the British forces under Sir Henry Clinton's immediate command would now be released, in all probability, for military operations in the North.

This was the dark moment chosen by Lt. Gen. Wilhelm von Knyphausen, then commanding the enemy forces at New York, for an invasion of New Jersey, ostensibly to test persistent rumors that war-weariness among the Americans had reached a point where, suitably encouraged, they might abandon the struggle for independence. Five thousand British and German troops accordingly crossed over from Staten Island to Elizabethtown Point on June 6, and the next morning began advancing toward Morristown. The first shock of their attack was met by the New Jersey Brigade, then guarding the American outposts; but as heavy fighting progressed, local militia came out in swarms to assist in opposing the invader. During the action, which lasted all day, the enemy burned Connecticut Farms. By nightfall, Knyphausen had come to within a half mile of Springfield. Then he retreated, in the midst of a terrific thunderstorm, to Elizabethtown Point.

Word of Knyphausen's crossing from Staten Island reached Washington in the early morning hours of June 7. There were then but six brigades of the Continental Army still encamped in Jockey Hollow—Hand's, Stark's, 1st and 2d Connecticut, and 1st and 2d Pennsylvania—the two Maryland Brigades having left for the South on April 17, and the New York Brigade having marched for the Hudson Highlands between May 29 and 31. The troops at Morristown, ordered to "march immediately" at 7 a. m., reached the Short Hills above Springfield that same afternoon. There the Commander in Chief held them in reserve against any British attempt to advance further toward Morristown.

Except for occasional shifts in advanced outposts on both sides, there was no significant change in this situation for 2 weeks. Knyphausen's troops continued at Elizabethtown Point, and the Americans remained at Springfield. On June 21, however, having learned positively that Sir Henry Clinton's forces had reached New York 4 days earlier, Washington decided that the time had come to leave Morristown as his main base of operations. Steps were accordingly taken to remove military stores concentrated in the village to interior points less vulnerable to immediate attack. Stark's and the New Jersey Brigades, Maj. Henry Lee's Light Horse Troop, and the militia were left at Springfield, under command of General Greene. The balance of the Continental Army began moving slowly toward Pompton, but was encamped at Rockaway Bridge when Washington, having left his headquarters in the Ford Mansion, joined it on June 23. This dual disposition of the American forces was taken with a view to protecting the environs of both Morristown and West Point, either of which might be the next major British objective.

On June 23, the very day of Washington's departure from Morristown, the enemy struck once more. This time, with one column headed by General Mathew and the other by Knyphausen, they succeeded in getting through Springfield, where the British burned every building but two. Greene's command met the assault with such determination, however, that the attackers again retreated to their former position. That night they abandoned Elizabethtown Point and crossed over to Staten Island. Never again during the Revolutionary War was there to be another major invasion of New Jersey.

While this second Battle of Springfield was in progress, Washington moved the main body of the Continental Army "back towards Morris Town five or six miles," where he would be in a better position to defend the stores remaining there in case the British attack should carry that far. Then, on June 25, with definite assurance that the enemy had retired to Staten Island, he put all the troops under marching orders for the Hudson Highlands. The second encampment at Morristown was ended.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |