|

HOPEWELL VILLAGE National Historic Site |

|

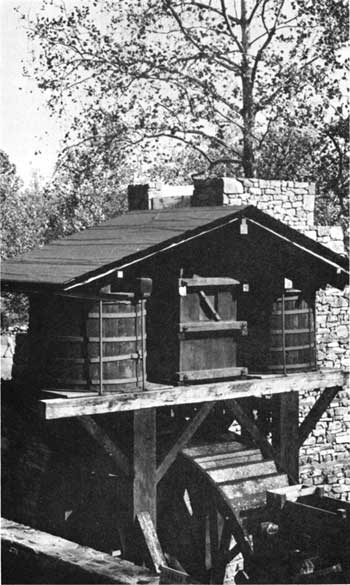

Hopewell water wheel and blast machinery restored in 1952.

William and Mark Bird and the Founding of Hopewell

Furnace

Among those far-seeing men whose imaginations became fired with the dream of building an American iron industry was William Bird, believed of Dutch ancestry and born in Raritan, N. J., in 1703. He went to work for Thomas Rutter, the pioneer ironmaster, at Pine Forge, where in 1733 he earned a woodchopper's wages of 2 shillings and 9 pence per cord.

Before very long, however, young Bird went into business for himself. He acquired extensive lands west of the Schuylkill in the vicinity of Hay Creek, where he built the New Pine Forges in 1744. At this time also he began the construction of Hopewell Forge, believed to have been located at, or near, the present Hopewell Furnace site. Later still, in 1755, he built Roxborough (Berkshire) Furnace. By 1756, he had taken up 12 tracts of land containing about 3,000 acres. The estate upon which his forges stood was alone valued at £13,000 in 1764; and long before his death, in 1761, he had become an important figure in the life of eastern Pennsylvania. His residence, built in 1751, can still be seen in Birdsboro, where it is now used by the Y. M. C. A. It serves as a good example of domestic architecture in that time and place.

Mark Bird, the enterprising son of William Bird, took charge of the family business upon his father's death in 1761, and soon expanded it. The next year, he went into partnership with George Ross, a prominent Lancaster lawyer, and together they built Mary Ann Furnace. This was the first blast furnace west of the Susquehanna River. Eight or nine years later, apparently abandoning or dismantling his father's earlier Hopewell Forge, Mark Bird erected Hopewell Furnace on French Creek, 5 miles from Birdsboro. The date 1770—71 is cut into a huge block of stone at one of the corners near the base of the Hopewell Furnace stack. At the same time, he built Gibraltar (Seyfert) Forge, also in Berks County. All the Birdsboro forges eventually came under his control, and to these works he added a slitting mill before 1779. An inventory of his properties lists for that year: 10,883 acres of land, 1 furnace, 2 forges and two-thirds interest in Spring Forge, 1 slitting mill, 1 saw mill, 2 pleasure carriages, 28 horses, 30 working oxen, 18 horned cattle, 12 negroes, 1 servant, and £3,767 cash. Bird also seems to have built a nailery about this time, although the tax lists do not mention it. Even after the Revolutionary War, when mounting debts fastened themselves on his investments, he continued to expand, building a forge and slitting mill in 1783 at the Falls of the Delaware River, opposite Trenton, in partnership with his brother-in-law, James Wilson.

The Boarding House, so named because many of the

workers obtained their meals there.

Photo by

Hallman.

Few details are available regarding the Hopewell of these years, for most of the original records are gone. In appearance, no doubt, it was not too different from the village of later years, with the furnace and adjoining structures as its center, and the office, Big House, barn, and tenant houses clustered about it. The inhabitants were mostly of Anglo-Saxon stock, in part original settlers and in part recent arrivals from the Old World. Very few of the early names reflect the German element, which predominated in this section. Most numerous perhaps were the Welsh (with names like Williams, Lewes, Davis, and Welsh), followed by the English. Among the English was Joseph Whitaker, a woodchopper who came to America with the British Army during the Revolution and settled near the furnace about 1782. Three of his many children who worked for the furnace in time became wealthy ironmasters, establishing ironworks in several States; and one of his great-grandsons—Samuel Whitaker Pennypacker—became Governor of Pennsylvania in 1903. These early workmen labored hard for Mark Bird, with whom they got along quite well.

That Mark Bird was prosperous, we may judge from the fact that in 1772 he became the highest taxpayer in the county, supplanting John Lesher, of Oley Furnace, and in 1774 the county increased the assessment on Hopewell Furnace sixfold. This expansion continued through the early years of the war.

By 1778, members of Bird's family were living in the Big House at Hopewell, which was enlarged, probably, in 1774. There is some doubt as to the years when Bird lived at Hopewell, but available evidence would seem to indicate from 1778, at least, to 1788.

The furnace had a production capacity of 700 tons per year before 1789, according to one contemporary authority, making it second only to Warwick Furnace with 1,200 tons. This estimate is probably correct, for in the blast of 1783, for which there is record, Hopewell produced 749-1/2 tons of pig iron and finished castings. Pig iron was its principal product, of course, with pots and kettles, stoves, hammers and anvils, and forge castings following in that order. The number of men employed is not known, but it was probably less than 50, including woodchoppers and colliers. The workmen were both freemen and indentured servants. An interesting entry in a surviving daybook for 1784 gives the names of five indentured workmen, two English and three Irish, and states that they were paid 14 pounds 8 shillings each—"as per Indenture"—upon the expiration of their terms of servitude. Negroes were also employed at Hopewell throughout its history, mostly as carters, but there is no indication that any of them were slaves. Bird did possess slaves and three of the four extant county assessment returns show that among his properties assessed for tax purposes there were 12 Negroes in 1779, 12 in 1781, and 2 in 1786, but it is not known whether any of them were employed at Hopewell or at one of Bird's forges.

|

|

Last Modified: Mon, Dec 2 2002 10:00:00 am PDT |